Advertisement

Peering Into The Placenta, 'Least Understood' And Respected Of Human Organs

Resume

If you've been pregnant, did you ever think about your placenta? Did you even have an image of it in your mind's eye?

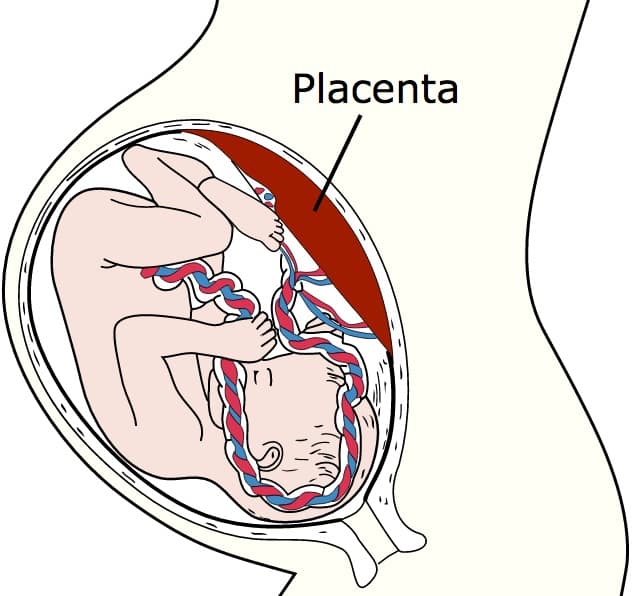

Your uterus, sure, especially as it grew and grew. Your fetus, of course, aided by grainy ultrasound print-outs. But your placenta, that essential life-support system, that unique biological bridge that is neither truly you nor your child -- probably not so much, unless you faced a rare and risky complication. (Or you're a member of the very small club that believes in eating bits of the afterbirth — please don't make me go there.)

Personally, through a miscarriage and two pregnancies, I never gave my placenta a single thought. But new research suggests that by ignoring the placenta, we may miss out — not just on a personal level but a societal one.

"The placenta is basically the last frontier in human organs," says radiologist Dr. P. Ellen Grant of Boston Children's Hospital. "It's the least understood, yet arguably one of the most important organs. For years it's been neglected, and we're only beginning to understand the complex role of the placenta in fetal development from conception to delivery, and in long-term outcomes not only for the fetus but also for the mother."

Dr. Grant's team has just won a nearly $5 million grant to develop better methods to image and monitor the placenta during pregnancy.

"The placenta is actually the Rodney Dangerfield of organs."

Dr. Diana Bianchi

It will focus in particular on pregnant women who are obese, a growing population that faces higher risks of complications, including pre-term birth, stillbirth and pre-eclampsia.

The grant is part of the Human Placenta Project, a major new federal effort that is funding a total of $46 million in research. The project aims to counter that longstanding neglect and increase understanding of the placenta's role in disease.

"The placenta is actually the Rodney Dangerfield of organs," says Dr. Diana Bianchi, executive director of the Mother Infant Research Institute at Tufts Medical Center, who was involved in the federal strategizing that led to the Human Placenta Project. (Note to young folks: Dangerfield was a comedian famed for his complaint, "I don't get no respect.")

"The placenta, until now, really hasn't gotten respect by funding authorities and it hasn't gotten a lot of attention," Bianchi continued. As parents-to-be focus on the fetus, she said, most "don't realize that the placenta is essentially the foundation for the normal development of the baby, because it supplies nutrients, it supplies oxygen, it takes the waste products away from the baby, and it also is an amazing machine for the production of hormones. So it's doing an amazing amount of work during the entire pregnancy, and yet at the very end of it, it's thrown out."

Given all that critical work, surely if the placenta falls down on the job in any way, complications of pregnancy may result.

Pre-eclampsia, a potentially life-threatening complication of pregnancy that affects up to 8 percent of mothers-to-be, is directly related to the placenta, Dr. Bianchi said. It involves "an abnormal development of the placenta, in that the placenta doesn't really invade the mother's uterus correctly, and the consequence of that is abnormal blood flow between the baby and its mother."

Obesity is so widespread in America that among some sub-populations of women, more than half are obese, Dr. Grant said.

And obesity is believed to affect placental function, she said, in ways that may both affect the pregnancy and lead to more obesity.

"There are many theories, substantiated by both animal and human research, suggesting that when mothers are obese, the placenta can be dysfunctional such that it increases the inflammatory mechanisms in the fetus, giving rise to long-term effects on inflammation, such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease," she said. "It can alter metabolism, giving rise to later obesity, or at least making the offspring more vulnerable to obesity."

Her research team will seek to study both lean and obese mothers-to-be, she said, aiming to improve noninvasive imaging techniques for normal pregnancies and to cast light on the specifics of how obesity may affect the placenta.

The project crosses disciplines from chemistry to radiology to computer science and crosses Boston institutions from MIT to Children's to Brigham and Women's to Mass. General.

Currently, it's often very difficult to diagnose placenta problems, Dr. Grant said. But in the future, "ideally, a pregnant mother would come in not only for a fetal screen but for a placental screen to monitor placental function. And if abnormalities in placental function are identified early in pregnancy, ideally we would be able to intervene."

That's still far away, of course. For now, as work progresses on Dr. Grant's project and 16 others to increase our understanding of the placenta, perhaps we can all just add a bit to our appreciation of the only organ that we grow only to discard.

Though the placenta exists only transiently, Dr. Grant said, it can have "dramatic effects on long-term genetic expression and disease vulnerability."

Further reading: The Mysterious Tree of a Newborn's Life: The Push To Understand the Placenta (The New York Times)

Dr. Grant's project Website: Monitoring Placental Health in Realtime