Advertisement

It's Not Just Heroin: Drug Cocktails Are Fueling The Overdose Crisis

A bald man in gray sweats bounds into the brick plaza next to City Hall.

"Hey," someone calls out, "where you been?"

"At the hospital," the man named Anthony says. "I OD'd."

A half dozen people watching shake their heads. It's a bad week in Chelsea, they say, with three overdose deaths.

"They're dropping like flies," says Theresa, a woman who manages a rooming house and does not want to share her last name.

Anthony, whose last name we’ve also agreed not to use, says he overdosed the night before on a particularly strong bag of heroin, laced with fentanyl, the dealer said, or something like it.

"[The dealer] told me how strong it was," Anthony says, "but everyone says that to sell their dope."

Fentanyl, an opiate that is many times more powerful than heroin, was present in about 37 percent of overdose deaths from January through June of last year, based on 502 cases analyzed by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Massachusetts.

What this chart from two Harvard researchers shows: "The most frequent drug category cited in overdose deaths was heroin (39.1%), followed by non-specified opioids (36.9%) and fentanyl (also 36.9%). Cocaine was cited in 23.4% of cases, ethanol (alcohol) 18.8%, and benzodiazepines 13.0%. “Chronic substance use," a vague description which did not refer to a specific drug class but infers that drug use was implicated in the death, was cited in 2.4% of cases. ... The vast majority of opioid-related overdose deaths in the first half of 2014 involved more than one drug."

Advertisement

Including his latest, Anthony says he has overdosed 12 times. Most of his near-death experiences did not include fentanyl -- as far as he knows. The really intense and dangerous highs were produced by heroin, sometimes with an alcohol chaser, and pills.

"The potency now is so inconsistent, you don’t know what to expect," Anthony says. "So you’ll eat a bunch of Klonopins and do a shot of heroin and then you’re dead."

When a heroin drug combo doesn’t kill you, "it intensifies the heroin high, and keeps you high longer," Anthony says.

Klonpin, Xanax and other anti-anxiety medications are benzodiazepines, also known as benzos. They showed up in 13 percent of Massachusetts overdose death cases sampled last year. The vast majority of deaths were caused by heroin in combination with some other drug or alcohol.

Using heroin in combination with other drugs is certainly not new. The speedball mix of heroin and cocaine that is present in some of the overdose deaths has been a popular high-risk choice for decades. Patients on methadone describe a popular cocktail taken after their daily dose of methadone treatment: Gabapentin (anti-seizure med), Klonopin, Clonidine (treats high blood pressure) and an over-the-counter allergy medicine.

Some heroin users we spoke with for this story did not want to comment out of fear that highlighting the heroin combo issue would restrict the supply of some of these drugs.

But as overdoses and overdose deaths rise, with the majority a result of multiple drugs, some doctors and patients are asking: What can we do?

Some heroin users say the answer is simple: Steer clear of combinations that increase the risk of an overdose.

"No combos for me," says a man who asks not to be identified. "I’ve seen a lot of my friends die."

This man had a scary experience with alcohol and benzos a few years ago. "When I mixed it with booze, that’s a bad combination for benzos. You know what I mean, you can end up off the bridge," he says.

But on the streets here in Chelsea, there’s a hot market for pills taken with heroin. These are drugs that slow respiration, the heart rate and produce other dangerous side effects.

"So you think, oh, it’s not a narcotic, it’s going to be OK," says a woman who gives her name as Nicole. "But little do you know that they all take a toll on your heart and on your breathing."

Nicole says some heroin users pill-shop, knowing which symptoms to mention so their doctor will prescribe something for anxiety or depression. Nicole says many patients addicted to heroin do have a legitimate need for these prescriptions.

"I think that the cocktail’s a more common thing than heroin is now."

Nicole

"You trust your doctor, you think, oh, my doctor’s giving this to me so it’s fine, nothing’s going to happen to me, like I’m prescribed to take it," Nicole says. "But people abuse it. I think that the cocktail’s a more common thing than heroin is now, or most people that take heroin take the cocktail as well."

Doctors who treat patients in recovery face difficult choices. Patients often describe increased anxiety, depression or trouble sleeping. But prescribing benzodiazepines to calm anxiety for someone who is on methadone can trigger an adverse reaction.

Doctors must make sure they understand the risks of prescribing medications in combination with an opiate and must explain those risks carefully to patients, says Dr. Kavita Babu, a toxicologist and associate professor of emergency medicine at UMass Medical School. "We have to be careful that we’re not just treating the side effects of the opioids themselves."

Babu says it's difficult for doctors to balance the science of drug interactions with a patient who is struggling, for whom an anti-anxiety med might help and when "managing patient expectations about how their pain or anxiety should be treated, sometimes our clinical knowledge falls apart at the bedside," she says.

Babu urges doctors to avoid prescribing opiates when possible to prevent addiction and to limit the supply of pills that might be abused.

"To move the needle on deaths," she says, "we have to change physician behavior as well as patient expectations."

The state has a database where hospitals and doctors post patient prescriptions and can check to see what patients are already taking. But many physicians say it’s hard to use and not reliable. State Public Health Commissioner Monica Bharel says the state plans upgrades early next year.

"As we work on improving the prescription monitoring system, it’ll allow prescribers to even more easily access this information and use it in their clinical judgment to help decrease these mixed cocktail deaths," Bharel says.

Doctors say it is helpful now to have information about the broad range of anxiety medication, cocaine, fentanyl and alcohol that was present along with heroin in overdose deaths last year.

"It’s a big problem," says Dr. Jim O'Connell, president of the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. "We’ve just been scratching the surface on it."

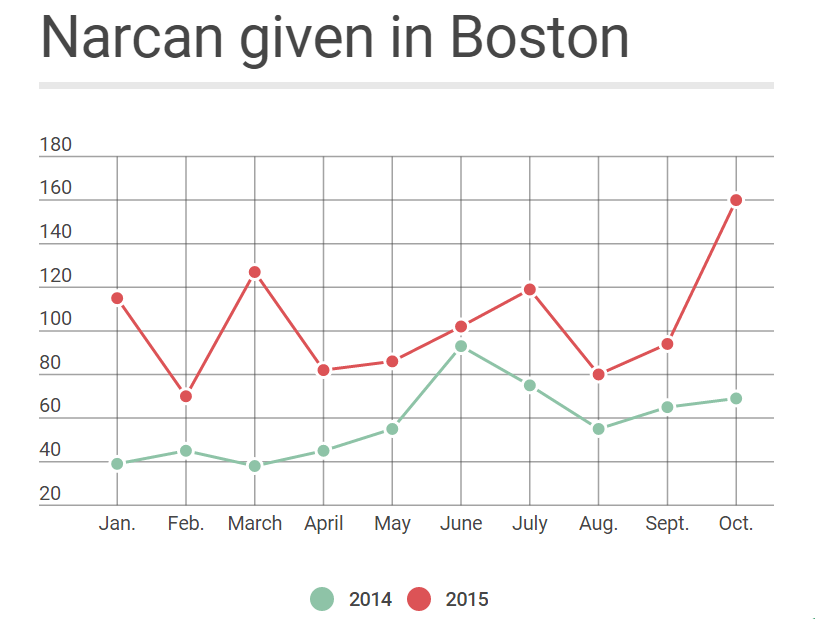

O’Connell says he needs more real-time information. Right now, he asks patients which pills are the hot sellers on the streets. That's a clue, O'Connell says, about what patients are taking in combination with heroin, and which pills he might avoid prescribing.

"We as doctors don’t really have a good sense of what we should be prescribing, what we shouldn’t," O'Connell says. "It’s really the combination of other drugs that is going to be the battle down the line."

Many addiction specialists say the battle must include ways to ease the pain that's at the root of addiction.

"There’s times when I really do want to die," says Anthony, who has intentionally overdosed under a bridge or in rooms where he thinks he won't be found.

When asked why he doesn't want to live, his face crumples into silent sobs.

"The more I do, the more guilt I feel, and the more I want to kill myself," Anthony says. "I can’t deal with the guilt and the pain and shame."

Anthony gets up from a bench near City Hall in Chelsea, clutching his hospital discharge notes in one hand. They say he’s to call his doctor and psychiatrist and schedule follow-up appointments after this last overdose. But he doesn’t have a phone. He borrows one, but gets the answering service and doesn’t leave a number -- just one more crack in a system that is struggling to understand and fight this raging heroin epidemic.