Advertisement

Public Bathrooms Become Ground Zero In The Opioid Epidemic

Resume

A man named Eddie threads through the mid-afternoon crowd in Cambridge's Central Square. He's headed for a sandwich shop, the first stop on a tour of public bathrooms available for drug use. Eddie, whose last name we're not including because he uses illegal drugs, knows which restrooms on Mass. Ave. he can enter, on what terms, at what hours and for how long.

"I know all the bathrooms that I can and can’t get high in," says Eddie, 39, pausing in front of plate glass windows through which we can see a bathroom door. Several restaurants, offices and a social service agency in this neighborhood have closed their restrooms in recent months, but not this sandwich shop.

"With these bathrooms here, you don’t need a key. If it’s vacant you go in. And then the staff just leaves you alone," Eddie says. "I know so many people who get high here."

At the fast food place right across the street, it’s much harder to get in and out.

"You don’t need a key, but they have a security guard that sits at the little table by the door, directly in front of the bathroom," Eddie says. Some guards require a receipt for admission to the bathroom, he says, but you can always grab one from the trash.

A national burrito chain a few stores down has installed bathroom door locks opened by a code that you get at the counter. But Eddie and his friends just wait by the door until a customer enters the restroom, then grab the door and enter as the customer leaves.

"For every 10 steps they use to safeguard against us doing something, we’re going to find 15 more to get over on their 10, that’s just how it is. I’m not saying that’s right, that’s just how it is," Eddie says.

Eddie is homeless and works in a restaurant. Public bathrooms are one of the few places where he can find privacy to shoot drugs. He doesn't use often these days. Eddie is on methadone, which curbs his craving for heroin, so he only uses occasionally to be social with friends.

Most of the bathrooms Eddie uses are not checked — once you get in, you won't be interrupted — or rescued.

"That’s why you have to have somebody with you to make sure that you don’t overdose," Eddie says. Eddie has used naloxone to revive his boyfriend and at least one other friend in the past few months.

He understands why restaurant owners are unnerved.

"These businesses, primarily, are like family businesses, middle class people coming in to grab a burger or a cup of coffee. They don’t expect to find somebody dead," Eddie says, "so I get it."

Managing Public Bathrooms 'A Tricky Thing'

Many businesses don't know what else to do. Some have installed low lighting, blue in particular, to make it difficult for drug users to find a vein.

The city of Cambridge plans to install a "Portland Loo" in the heart of Central Square by the end of the summer. Some business owners hope it will relieve pressure on their bathrooms. Others worry it will become a haven for drug use.

"There's a need for public toilets and there's a concern about whether they will have a negative impact," says George Metzger, a senior principal at HMFH architects and a past president of the Central Square Business Association.

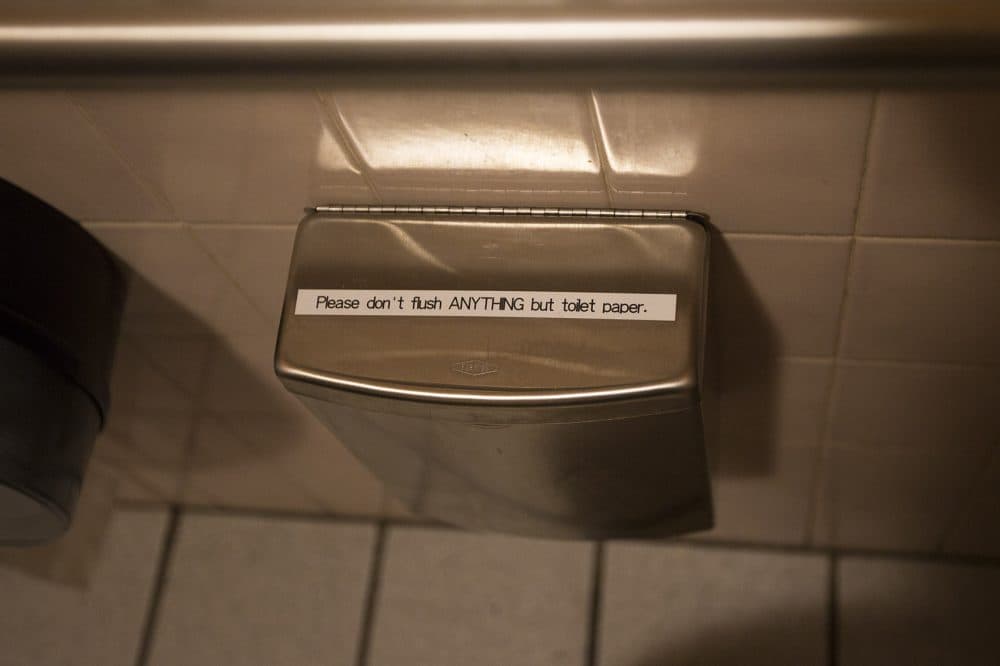

The bathrooms at 1369 Coffee House in Central Square are still open for customers who request the key code from staff at the counter. Owner Joshua Gerber has done some remodeling to make the bathrooms safer. There's a metal box in the wall next to his toilet for needles and other things that clog pipes. And Gerber removed the dropped ceilings in his bathrooms after noticing things tucked above the tiles.

"We’d find needles or people’s drugs," Gerber says. "It’s a tricky thing, managing a public restroom in a big, busy square like Central Square where there’s a lot of drug use."

Gerber and his staff have found several people, on the bathroom floor in recent years, not breathing.

"It’s very scary," Gerber says. His eyes drop briefly. "In an ideal world, users would have safe places to go that it didn’t become the job of a business to manage that and to look after them and make sure that they were OK."

There are such safe use places in Canada and some European countries, but not in the U.S. So Gerber is taking the unusual step of training his baristas to use naloxone, the drug that reverses most opioid overdoses. He sent a training invitation email to all employees last week. Within 10 minutes he had about 25 replies.

"Mostly capital yes, exclamation point, exclamation point. 'I’ll be there for sure!' 'Count me in!' " Gerber recalls with a grin. "You know, just thrilled to figure out how they might be able to save a life."

Finding Safe Space In Hospital Bathrooms

Naloxone has become standard equipment for security guards at many hospitals in the Boston area.

"I carry it on me every day, it’s right here in a little pouch," says Ryan Curran, a police and security operations manager at Massachusetts General Hospital, pulling a small black bag out of his suit jacket pocket. Ryan stands outside a bathroom in the main lobby at MGH where a woman overdosed last fall. She survived, as have seven or eight people who overdosed in MGH bathrooms since Curran’s team started carrying naloxone in the last year or year and a half.

"It’s definitely relieving when you see someone breathing again when two, three minutes beforehand they looked lifeless," Curran says. "A couple of pumps of the nasal spray and they’re doing better. It’s pretty incredible."

Mass General began training security guards after emergency room physician Dr. Ali Raja realized that the hospital’s bathrooms had become a safe haven for some of his overdose patients.

"There’s an understanding that if you overdose in and around a hospital that you’re much more likely to be able to be treated," Raja says, "and so we’re finding patients in our restrooms, we’re finding patients in our lobbies who are shooting up or taking their prescription pain medications."

Many businesses, including hospitals and clinics, don’t want to talk about overdoses within their buildings. Curran wants to be sure Mass General's message on drug use is clear.

"We don’t want to promote, obviously, people coming here and using it, but if it’s gonna happen, then we’d like to be prepared to help them and save them and get them to the ED [Emergency Department] as fast as possible," Curran says.

Speed is critical, especially now, when heroin is routinely mixed with fentanyl. Some clinics and restaurants check on bathroom users by having staff knock on the door after 10 or 15 minutes, but fentanyl can lead to oxygen-deprived brain death within that window. One clinic has installed an intercom and requires people to respond. Another has designed a reverse motion detector that sets off an alarm if there’s no movement in the bathroom.

Limits On Discussion And Direction

During an epidemic, you might think public health officials would issue safety practices for bathrooms but there's very little discussion of the problem in public. Here's why.

"It’s against federal and state law to provide a space where people can use knowingly, so that is a big deterrent from people talking about this problem," says Dr. Alex Walley, director of the addiction medicine fellowship at Boston Medical Center.

Without some guidance, more libraries, town halls and businesses are closing their bathrooms to the public. That means more drug use, injuries and discarded needles in parks and on city streets.

Walley and other physicians who work with addiction patients say there are lots of ways to make bathrooms safer for the public and for drug users. A model restroom would be clean and well-lit with stainless steel surfaces — but few cracks and crevices for hiding drug paraphernalia. It would have a bio hazard box for needles and bloodied swabs. It would be stocked with naloxone and perhaps sterile water. The door would open out so that a collapsed body would not block entry. It would be easy to unlock from the outside. And it would be monitored, preferably by a nurse or EMT.

There are very few bathrooms that fit this model in the U.S.

Walley says, for now, drug users and people who manage public bathrooms are caught in a sort of catch-22. "There's just not a good answer for this," Walley says.

In the area around Boston Medical Center, wholesalers, gas station owners and industrial facilities are looking into renting portable bathrooms.

"They're very concerned for their businesses," says Sue Sullivan, director of the Newmarket Business Association, which represents 235 companies and 28,000 employees. "But they don't want to just move the problem. They want to solve the problem."

Some doctors, nurses and public health workers who help addiction patients every day argue the solution will have to include safe injection sites, where drug users can get high with medical supervision.

"There are limits to better bathroom management," says Daniel Raymond, deputy director for policy and planning at the New York-based Harm Reduction Coalition. If communities like Boston start to reach a breaking point with bathrooms, "having dedicated facilities like safer drug consumption spaces is the best bet for a long-term structural solution that I think a lot of business owners could buy into."

Maybe. No business groups in Massachusetts have come out in support of such spaces yet.

This segment aired on April 3, 2017.