Advertisement

March For Science Moments: Harvard Dean's Outrage, Stories Of Lives Saved

"As an American, I'm outraged," Harvard Medical School Dean Dr. George Q. Daley told the crowd, referring to looming federal cuts. "As a physician, I'm terrified. Terrified of what this will mean for humanity, of what humanity will suffer in the future because of problematic policies that are being considered today."

Dr. Daley was speaking to more than 500 people gathered on the medical school's quad in the Longwood Medical Area before they headed to Boston Common for the city's March For Science.

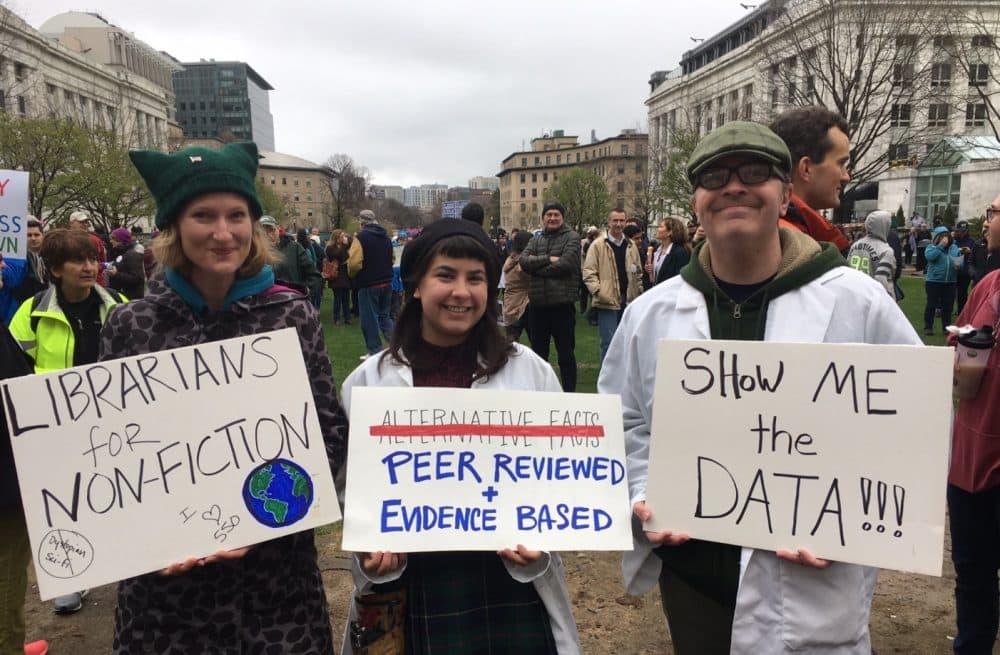

One march theme Saturday was the call for researchers to lift their heads from their lab benches and speak out in favor of science and to ensure that solid evidence informs policy decisions. Here are excerpts from four who did on Saturday:

Harvard Medical School Dean Daley:

Make no mistake. Like a slow-growing but ultimately malignant cancer, the metastasizing doubt of science will lead to harmful decisions and reckless policies.

The attack on science is the result of a schism in our society that is more fundamental and far deeper than any political divide. The attack on science is a rift that signifies a dangerously widening chasm between critical thinking and rigid ideology.

One of the most dangerous and most egregious consequences of this rift is the looming cuts in [the] NIH [National Institutes of Health] budget.

If it stands, the proposal to slash nearly one-fifth of the NIH budget will be devastating to American biomedicine.

The human toll of these cuts will be immediately devastating, certainly here in the Longwood Medical Area and the Boston area, but I fear the effects over the long term could haunt us for generations.

These cuts will not just destabilize the economy, they will essentially eliminate a generation of young scientists.

Cuts of this magnitude also pose an existential threat to America’s preeminence as a world leader in biomedicine.

If you're taking a drug — to control heart failure or treat HIV infection — you are the beneficiary of therapies sparked by federal investment in science.

Chances are your drug originated, in some way shape or form, somewhere on an academic campus, in a cluttered lab, just like the ones that surround us. These academic labs study fundamental processes of life and they spark therapies that we now take for granted.

Millions of people, even billions around the world, are alive today because of life-saving, life-sustaining and life-altering treatments that emerged from curiosity-driven research.

Harvard Medical and Public Policy student Elorm Avakame:

.... A couple of days later, as I was rounding on my patients at the crack of dawn, I saw Elena [a young patient with sickle-cell anemia] again, in that same pose, fists clenched by her side, breathing those same painful breaths, crying those same silent tears. And my heart shattered into a million pieces.

But around that same time, I came across an article describing experimental techniques for treating patients like Elena. Sitting alone in my room, reading about procedures to alter the marrow in her little bones, I felt something stirring in my soul. I felt hope. Hope for a day when patients like Elena would be free from pain forever. Hope for a day when patients like my own cousin, whose blood sickled in his veins, would not have to leave this world before their time.

This is the promise of science. This is why we seek to unlock the mysteries of the natural world. For so many patients like Elena who are afflicted with their own conditions, for so many families who take strength in the hope that a day will come that brings relief from the burden of disease. And this promise is what is at stake today.

In an era in which funding for scientific research dwindles with each new presidential budget, we form a potentially large and powerful constituency that has yet to be activated. But if we are to maintain the pursuit of discovery for the betterment of humankind, we must make our voices heard in the halls of power.

It is time for us to step off of the sidelines and into the fray. Let us be fervently engaged at every level of the political process, making lawmakers know that scientific research is not a line item to be slashed during moments of budgetary constraint. It is among the fundamental pillars of our society. [...]

This is not a fight for our livelihoods. This is a fight for human lives.

Dr. Katherine Helming Walsh, cancer survivor and cancer researcher at the Broad Institute:

When I was diagnosed with leukemia, my world shifted in a radical and ironic way. I had just begin to fulfill my dream of advancing medical knowledge specifically in the field of cancer biology. I was so excited to be taking classes from world-class experts and conducting cutting-edge research.

I went from being a busy graduate student researcher in one of Dana-Farber's laboratories to being a very sick patient in one of the hospital rooms. Thanks to an incredible team of doctors and nurses at Dana-Farber and Brigham and Women's Hospital, my amazingly supportive network of family and friends, and decades of dedicated biomedical research, I am here today, cancer-free and back in the laboratory, conducting the research that I originally set out to do, now with a renewed passion and vigor.

I would not be here today if it were not the persistence, the creativity and the courage of the many scientists who came before all of us. In sight of where we are standing right now, just over there, Dr. Sidney Farber consulted the very first trials with folate acid antagonists in the 1940s, that would become the basis for modern-day methotrexate and other chemotherapies, a drug that was a key component of the treatment regimen that saved my life.

A diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a child was a death sentence before Dr. Farber's work, and now nearly 90 percent of cases are curable.

[...]

My life was saved thanks to multiple discoveries from innovative biomedical researchers working over the span of more than six decades.

11-year-old Emily Coughlin, who benefited from a cutting-edge treatment for a high-risk cancer, also attended, with her mother, Amy, who said in part:

Emily was diagnosed with stage 4 high-risk neuroblastoma in May of 2009, a month before her fourth birthday. We had never heard of neuroblastoma, and we were told not to Google anything about it.

The question we had is: What are the odds? Show me the odds. But neuroblastoma's numbers eight years ago weren't all that comforting. Fifty-fifty, we were told. That's a coin-toss, with half of the kids losing. The protocol in place at the time had shown some success, but there was so much left to chance. I wanted better numbers. I wanted better odds. I wanted there to be a concrete protocol in place that worked every single time. I was terrified that I would lose her. Beyond terrified.

There was another option. We were given the opportunity to go to trial, and Emily would be randomized for one stem-cell transplant or two. She was randomized for two. Looking back, had I known that my Emily would be sicker than a parent can imagine their child, or known the feeling of watching your daughter fight for her life in the ICU when the best team of doctors can't tell you what's wrong with her, I might not have tossed her name in the hat.

But that would have been a mistake. Because although Emily's kidneys were severely damaged during one of her two transplants, her height and hearing compromised by the drugs given to eradicate her cancer, her endocrine system attacked with toxicity that would affect her long after her treatment was finished, she's here with me today.

That's research. It's messy and scary and completely necessary to save the people that we love. Research is putting absolute trust and faith in doctors and scientists to cure your daughter. Research is the hope you have when the old way of doing things has failed for some.

The heroes of research are the courageous kids who fight to see if the treatment is going to work. It's also the scientists who are relentless in making sure that it does. They're both the ones who give hope to the kids today who are diagnosed with neuroblastoma, the next four-year-old Emily, and the one after that.

Research saved Emily's life. It gave me the gift of my spunky little girl, who regularly argues with me about what's for dinner, what she's going to wear and why I won't let her on social media. Research gave me the gift of a middle-school daughter, when there were many dark days that I didn't know if I would have one.