Advertisement

BioBoom

Could The 'BioBoom' Go Bust? How One MIT Professor Sees It

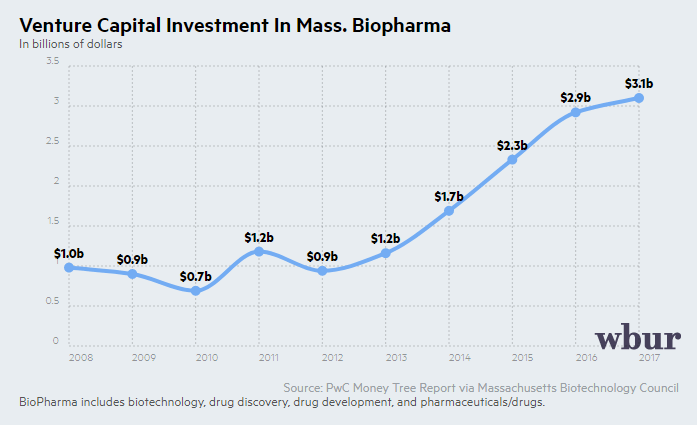

There's big money in biotech in the Greater Boston area. Last year, venture capital firms invested more than $3 billion in the state's biotech and pharmaceutical companies, according to the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council. The amount has risen every year since 2012:

Local companies have already produced revolutionary treatments for rare diseases, cancer and more. And there's promise and hope for cures and treatments still to come. Because of that, there's no shortage of capital.

Biotech companies often go public even if they haven't yet put a product on the market, let alone turned a profit.

MIT finance professor Andrew Lo says there's good reason for so much exuberance.

"It's because there are lots of breakthroughs that are happening literally on a daily basis. Diseases that were death threats now are cured. The problem is that we don't know exactly how much capital is just the right amount. And so, given that there is so much exuberance, it's not surprising that we might ultimately end up over-investing."

Lo himself invests in biotech. He and other industry players and experts differ on whether biotech is in an economic bubble that could break.

"We don't always know whether we're in a bubble until after it's burst," explains Lo, who directs the Laboratory for Financial Engineering at the MIT Sloan School of Management. "So I would say that in certain areas, it certainly looks like a bubble. For example, in cancer therapeutics — lots and lots of really exciting breakthroughs — but the valuations are sky high. So I think we do have to be cautious about where we're heading."

Lo says some bad outcomes could make investors run for the exits.

"For example, if it turns out that some of the recent cancer immunotherapies ultimately end up having some nasty side effects that end up causing cancer to spread more quickly," Lo says. "I think that's unlikely, but you never know. ... That could actually hurt the entire industry."

Industries that are growing and innovating and attracting big money are, by definition, volatile. Lo told WBUR's All Things Considered host Lisa Mullins that biotech investors have to be in it for the long haul.

Advertisement

This transcript has been lightly edited.

Andrew Lo: There are three things that make the biotechnology industry really challenging for investors. One, it takes hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars to develop a single successful drug. Second, it takes on the order of 10 to 15 years, not 12 to 18 months, for you to be able to figure out whether or not you've got a successful drug. And third, the probability of success, particularly in a field like cancer, is right now about 5 percent — which is very different than the probability of developing a successful app.

Lisa Mullins: OK, so the venture capitalist mind would presumably think, "Yeah, but the returns are going to be really good further on down the line."

Right. So what that means is that in order for you to be able to get that winner, you now have to invest across a lot more bets. You have to make more bets in order to be able to get that one or two winners that will pay for all of the other losers.

Think of a drug where this is happening right now.

For example, there's a company called Spark Therapeutics based in Philadelphia that just announced at a recent hemophilia conference that they have some very promising results for a gene therapy that looks like it could fix hemophiliacs permanently. If that's true, it's going to be a godsend for these people that have the disease. And it actually will ultimately save the health care system a lot of money, because right now we pay extraordinary amounts of costs for these blood transfusions and clotting factors for these hemophiliacs. But it turns out that there are two other companies developing similar drugs. ... And if you're second or third, it might be that you make nothing out of this and you've spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing it.

"You have to wait 10 years, and at the end of that process there's a one in 20 chance that you'll come up with a cancer drug -- which if you do is worth $12.3 billion."

Andrew Lo

You have an example of kind of looking at the risk and how these companies might see the risk of investment by the image of a jar...

Imagine you have a jar with 20 balls and of these 20 balls, 19 of them are colored black and one of them is colored red. And your job is to pick a ball out of this jar. You don't get to look inside the jar first — you have to just pick the ball blindly. And if you pick the color red, I'll pay you $12.3 billion.

But there's only one red one.

But there's only one red one. And if you pick a black one, you get nothing. And by the way, in order to pick a ball from the jar, you have to pay me $200 million now. Well, that's what it is to develop a cancer drug. It takes $200 million in out-of-pocket costs. You have to wait 10 years, and at the end of that process there's a one in 20 chance that you'll come up with a cancer drug — which if you do is worth $12.3 billion. But in most cases, 19 out of 20 times, you come up with nothing. And that's the challenge.

You come from a very interesting perspective on this, because you are speaking as somebody who has studied financial strategies and investment. You're speaking as someone who has invested yourself and invests. And you're speaking as someone who, like most people in the audience, has been affected by losing people very close to them with cancer. Many people reading have also been affected by cancer personally. How does that influence your perspective on this?

I have to admit that I had no interest in health care or health care investing for many many years. ... And I got interested in health care, really, for personal reasons. A number of friends and my mother developed various kinds of cancer over the last few years. And within the space of about four years, I lost six people to cancer and was just really deeply affected by that. ... And the more I learned about the way that cancer drugs are developed, the more I realized that finance actually plays a central role in how these drugs come to market. And risk really seems to be at the core of the challenge. So if we can use finance to reduce the risk, we will actually be able to bring lots more capital into the industry and be able to get therapies to patients faster. We need to use the power of the financial markets to raise even more capital.

Lo would like mutual fund companies to create funds that focus solely on biotech — for example, a fund centered on cancer research. The funds would attract individual investors, including people who've been personally affected by cancer. That would generate a larger pool of investors. The funds would back late-stage research in addition to early-stage startups, thereby helping to lessen the risk.

He stresses that any kind of innovation is subject to financial bubbles and bursts. But designing a new mode of investing is one tool to keep biotech research on track.

"I'm not sure that it'll stop a biotech bubble from bursting," Lo says. "But it can certainly reduce its impact on drug development. If there are alternative sources of capital that can actually provide the long-term investments that you really need to develop these drugs, then short-term blips may not matter as much."

This segment aired on June 8, 2018.