Advertisement

For High Schoolers Brought To U.S. Illegally, Planning The Future Is Trickier Than Ever

Hundreds of Boston high school students took to the State House and Boston City Hall Monday with a list of demands about public education, immigration and racism, in the wake of the election of Donald Trump. Among their demands, the students asked Mayor Marty Walsh and Gov. Charlie Baker to push for greater protections of students who were brought to the country illegally.

That’s an issue that high school counselors are navigating every day — and it’s often tricky, in light of the president-elect’s promise to defund programs like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. DACA, as it’s called, allows children who were brought here illegally to study and work in the United States.

Ask just about any teacher or school counselor why they got into education, and most will tell you it’s because they want to help students do well in life and contribute to society. But when you're working with students who arrived illegally, many times the job becomes the delicate task of managing expectations.

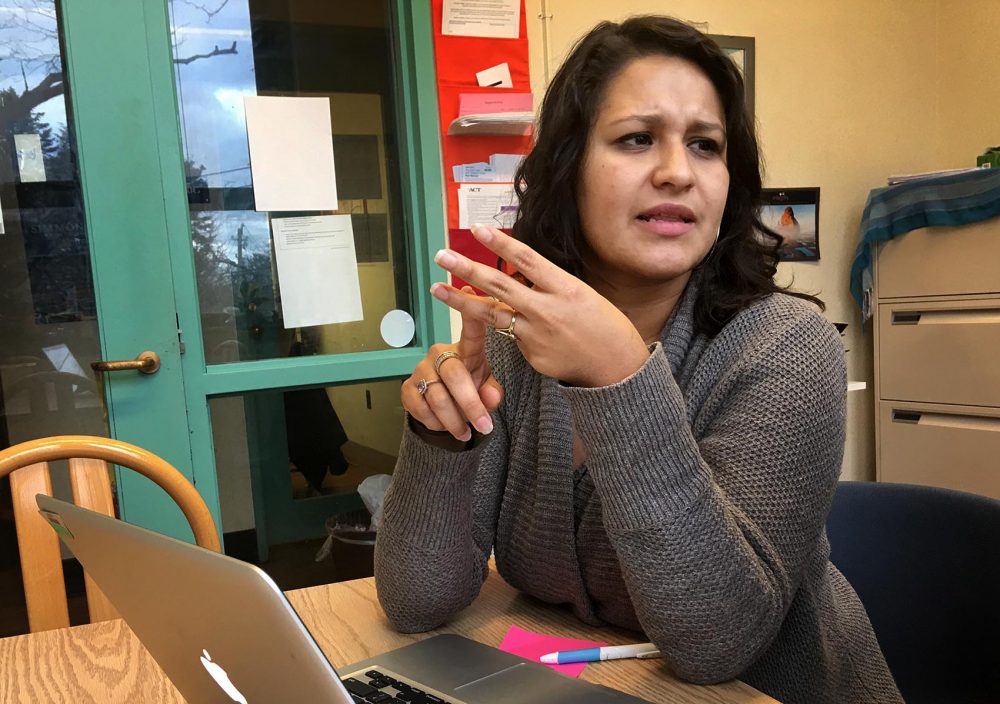

Claudia Martinez does that work all the time. She's a guidance counselor at Boston Latin Academy, and she recently started a district-wide group called “Unafraid Educators.” It’s made up of about 30 teachers and counselors who help students brought here illegally with such tasks as applying to college or making sense of their legal rights.

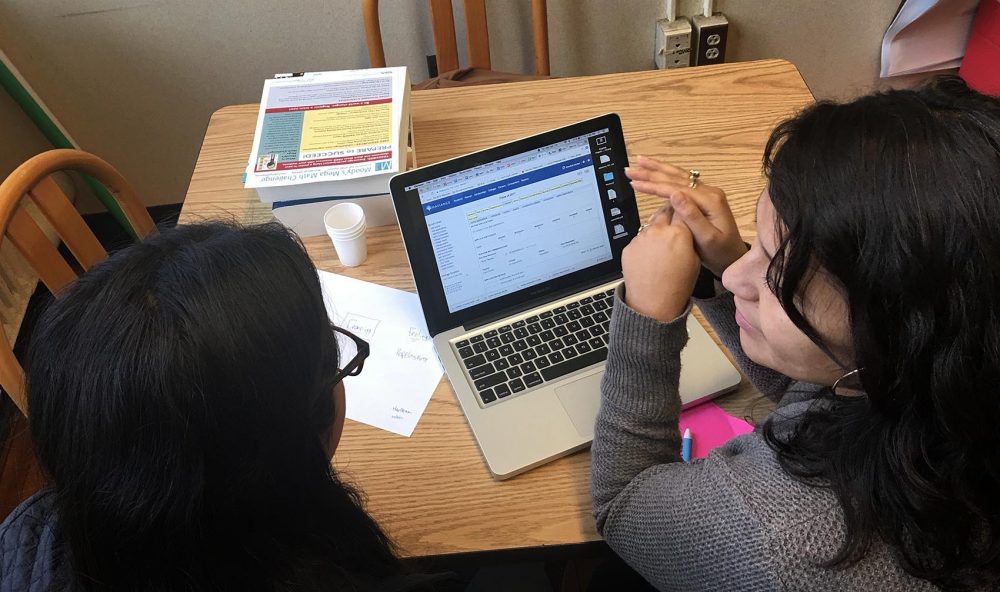

On a recent day, Martinez was going over college options with 17-year-old Ledys, a senior at Boston Latin Academy. (At the school’s request, we’re only using students’ first names in order to protect their personal safety.) Ledys’ mom and dad brought her here illegally from Honduras when she was 4.

Ledys is a good student, but likely not good enough to get into some of the Ivy League schools that provide financial aid to students who didn’t come here legally. Ledys’ dad cleans office buildings; her mom works at a fast-food restaurant.

And so Martinez — whose office walls display the flags of Harvard and Cornell as inspiration for her students — finds herself giving students like Ledys tips like these: Choose a college you and your parents can pay for out of pocket, and find a college that won’t ask if you’re a legal resident.

“I think the most heartbreaking students and situations for me,” Martinez said, “are my undocumented students with 3.0’s or 3.5’s who are strong academically but might not be like the top, top of the class.”

Advertisement

But Martinez is up for doing whatever she can to help her students.

Her Unafraid Educators group has spent quite a bit of time lately helping students look at their options under a Trump administration.

“Mostly I’ve had students come to me crying and scared and afraid around just what is going to happen to them and their families,” Martinez said.

And what does she say?

“I don’t know, but that I am committed to them and that I will go to bat for them and that I will move mountains for them.”

For 16-year-old Camila, knocking on Martinez’s door the day after the election quickly found her a shoulder to cry on.

“We didn’t know what to do, so we just came here,” Camila recalled. “And she just told us that we shouldn’t give up. Like, there’s always people out there that are gonna help us.”

Camila is originally from Colombia. She entered the country illegally with her parents when she was 8. At 16, she has decided to put some of her dreams on hold.

“When I was little I wanted to do a lot of stuff,” she said. “Like, I wanted to be a lawyer, then I wanted to be in the medical field — but I really want to, and that’s not an option anymore.”

Camila said those professions are not an option because they require a lot of schooling — and her parents don’t have the money. And besides, she said, her mom and dad need her at home for practical purposes. They don’t speak English.

It’s hard, she said, to reconcile two facts: They brought her here for a better education, and yet their status may hold her back from fulfilling her dreams.

“It’s, like, the big elephant in the room,” Camila said. “We all know, and we know the situation, but we don’t want to talk about it, because it’s just too hard. They don’t want to limit me. They want me to go far. And I want to go far. But I don’t think it’s possible.”

These are the hardest conversations for counselor Martinez. Her No. 1 goal, she said, is to make sure students brought here illegally know they have options before they decide to give up. With Ledys, for example, she has helped her narrow in on a few colleges in Massachusetts. Ledys said the whole process has been a big wake-up call.

“When I was younger, people would tell me it’s always about what you want,” she said. “And I come here, and I’m realizing that it is what I want, but there’s always obstacles. And money has become one of the biggest issues.”

Ledys is looking at scholarships, and possibly community college, so that she can pay for it herself.

She wants to be an early childhood teacher, like the one who taught her English when she came here from Honduras at age 4.

Most of the time, she's thinking about her parents.

“I want both my parents — I want them proud of me,” she said.

Like many students brought to the United States illegally, Ledys carries the burden of wanting to make her parents’ choices worth it.

This segment aired on December 6, 2016.