Advertisement

Dealing With Dyslexia, Starting With One Family's Battle For A Diagnosis

Resume

Most schools in Massachusetts don't screen for dyslexia, even though experts say diagnosing the learning disability early is the key to successful interventions.

Instead, many districts wait until a child shows obvious signs of trouble reading or writing. Some advocates say by then, it's too late.

One Family's Struggle

By 6 p.m. most evenings, Beverly Hilaire is on a mad dash to get dinner done. Her sons are tired and hungry. "I have a small window before they start getting demanding," says Hiliare, as she stirs and mixes food on a stove.

Monday through Friday, 11-year-old Stephen and 9-year-old Harrison travel back and forth from the Landmark School in Manchester-By-The-Sea to their home in West Roxbury. That's more than 100 miles a day round trip.

To pass the time, Stephen says, "what I prefer doing is my homework on the bus so that when you get home you don’t have to do it."

Hilaire says the fact that Stephen can do his homework on the bus without her help, is proof the commute is worth it. Landmark is a private school for kids with dyslexia. When Stephen, who is in the fifth grade, and Harrison in third, started at Landmark eight months ago, they could barely read.

"They are the solution that I was looking for," says Hilaire, though Landmark was not her first choice. She and her husband bought a home in West Roxbury so that their kids could attend the Ohrenberger, a Boston Public School right down the street from their new home.

The reasons, Hilaire says, were simple: "One is for my children not to be subjected to street violence and get shot at or hear sirens all day. The other is for them to have a better choice of schools. I thought, if we could survive the streets and we could survive school, I have a chance of getting these little boys to where they need to be in life."

But from Hilaire's view, the district's policies on diagnosing dyslexic students failed Harrison and Stephen.

How Schools Handle Screening

When both of the boys were in first grade, BPS teachers noticed they had problems reading and writing. District specialists determined both boys have what's called "Specific Learning Disability." The state's education department describes it as a multitude of disorders including problems in "understanding or using written and spoken language."

Hilaire's youngest son had the hardest time. "He was really frustrated for first grade, second grade, and having the meltdown of not being able to grasp it all." Both boys, she says, were often taken out of class for extra instruction. But with no pinpointed diagnosis, Hilaire says she had problems helping them at home. And she didn't see much improvement in their reading and writing.

Stephen, who once loved school, would come home crying. "When I wasn't mad, I was frustrated," his mother says. "And when I wasn’t frustrated I was probably feeling like I was failing. And I felt trapped."

After reading about dyslexia on the internet, Hilaire was all but certain her sons had the reading disorder. But Boston Public Schools never used that term. What she didn't know is that school systems in Massachusetts don't diagnose dyslexia. Only an outside medical professional can do that. This is where it gets confusing for parents like Hilaire. A school can recommend dyslexic testing, but if a parent wants a test without a recommendation, it can cost more than a thousand dollars out of pocket. It can also take up to a year to get an appointment for testing at places like Boston Children's Hospital or Massachusetts General Hospital.

"The schools begrudge everyone the label, OK? Easy for no one," says Nancy Duggan, the co-founder of the Massachusetts chapter of the advocacy group Decoding Dyslexia. "You must have the money, the resources and even the inkling, someone needs to whisper the word in your ear and you need to do some research before the word dyslexia even helps you."

Duggan's group is hoping for the passage of a bill that would require school districts in Massachusetts to screen for dyslexia as early as kindergarten. According to the International Dyslexia Association, as of 2015, 28 states have similar legislation. The bills will go before the Joint Committee on Education of the Massachusetts Legislature in July.

Some educators, however, have argued it is too expensive to test all children for a disability that only affects 10 to 15 percent of the population.

"The one thing about dyslexia that's hard is that there's not one test that diagnoses dyslexia. It's an aggregation of a bunch of different assessments and sub-tests," says Cindie Neilson, assistant superintendent for special education with BPS.

'Didn’t Feel Like I Had A Choice'

Neilson says she can't speak specifically about Harrison and Stephen's cases, but she says, beginning in the fall, BPS will start screening kindergartners, first and second graders for markers that are present in children who suffer from dyslexia. The screening won't be a specific test to identify dyslexia, but Neilson says it will help narrow in on potential problems.

The process of determining a learning plan can sometimes take years. Hilaire felt her boys didn't have time to wait.

"I have two children who are going through and falling apart in front of me every day," she said. "So I didn’t feel like I had a choice to ignore it, prolong it."

After nearly two years of back and forth with BPS, Harrison and Stephen were tested for dyslexia at Mass General, and the results confirmed they are severely dyslexic.

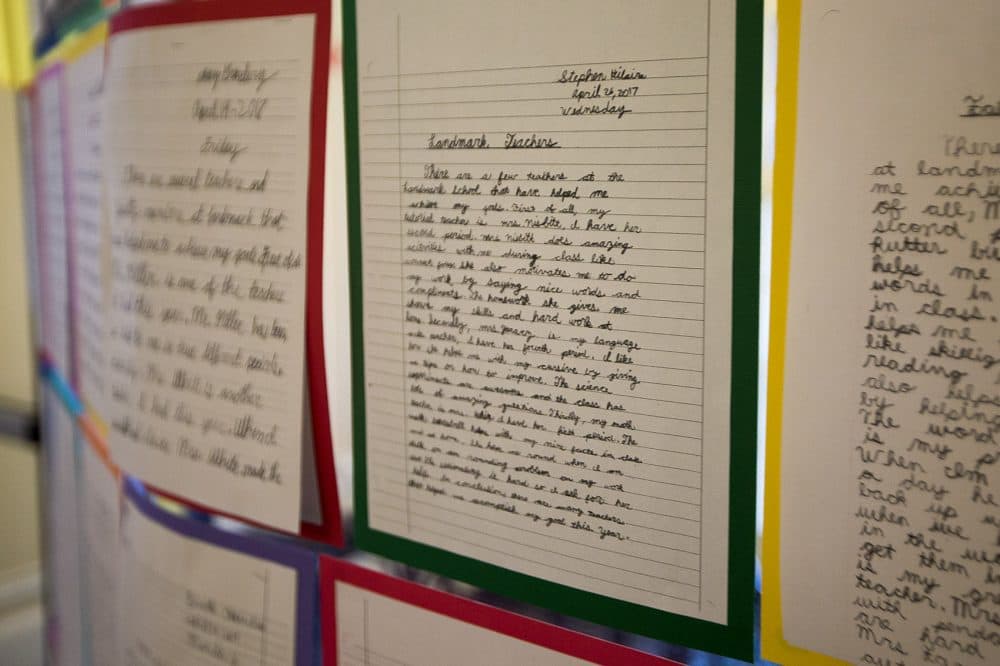

Both are now thriving at Landmark. On the second floor of the school, is a wall covered with essays written by fifth graders. Stephen walks over to his essay about one of his favorite teachers, and then begins to read: "Miss Nisbett does amazing activities with me during class like Connect 4. She also motivates me to do my work by saying nice words and compliments."

Stephen's progress is exactly what his mother and father had hoped for. Hilaire says she feels for families that can't afford to travel hours for treatment. Her hope is that one day soon, all schools throughout the state will be able to service and treat dyslexic students.

For more information and resources on dyslexia: The Gaab Lab, Decoding Dyslexia, The Landmark School and the International Dyslexia Association.

Correction: In an earlier version we misspelled Stephen's teacher's name. The correct spelling is Nisbett. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on May 30, 2017.

This segment aired on May 30, 2017.