Advertisement

Why Wheelock College Wants To Merge With Boston University

Resume

For almost 150 years, Wheelock College has been proudly small.

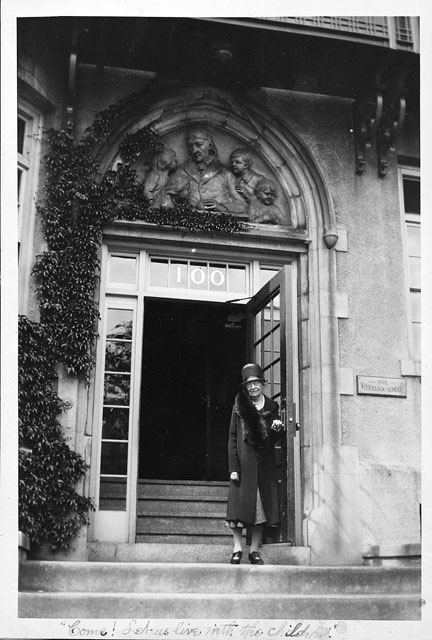

It began in 1888, as Miss Wheelock’s Kindergarten Training School.

"Miss Wheelock" was Lucy Wheelock, a teacher who saw Boston neighborhoods filling with Portuguese, Filipino and Italian immigrants and founded a school to train their teachers. During her 50 years as the school's leader, Lucy Wheelock presented education, especially of young immigrant children, as "the greatest good of mankind."

That sense of mission has animated Wheelock College ever since. The school still produces lots of early-childhood educators, as well as social workers and child psychologists.

But lately that kind of smallness has begun to work against many American colleges. Schools like Wheelock have experienced a perilous cycle of shrinking enrollment and rising costs over the past decade.

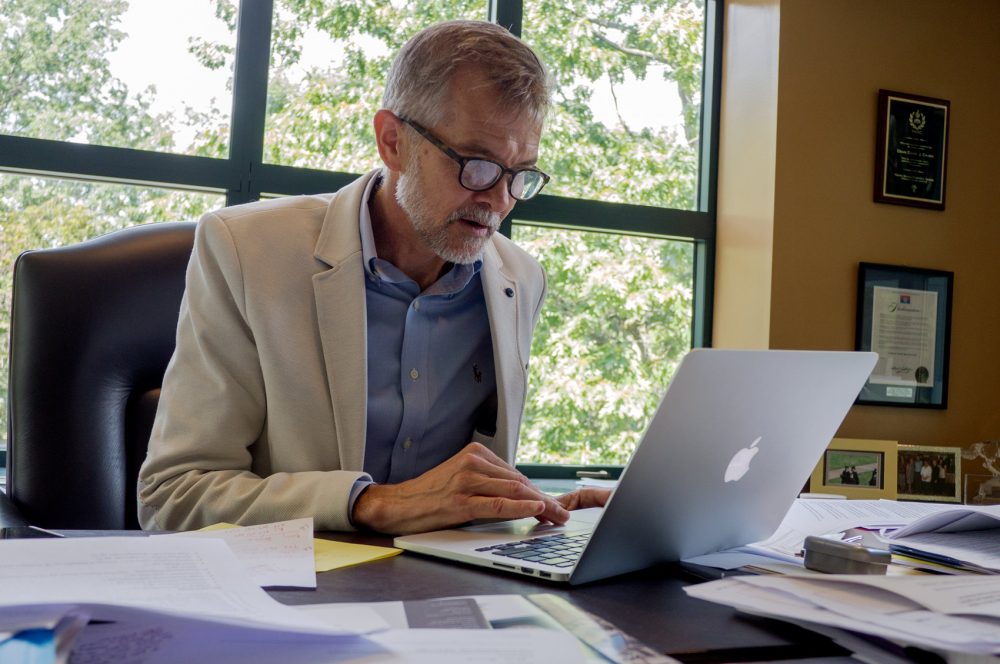

Wheelock's president, David J. Chard, says that means the leaders of small colleges like himself will have to get creative. And Chard's creative solution to Wheelock's problem is to seek safe harbor in a merger with the much larger Boston University, its school of education in particular.

Chard has only headed Wheelock since July of last year. He says its founder has been on his mind a lot lately: "I've often thought, over the last several months, 'What would Lucy Wheelock do if she were here today?' "

Chard took over Miss Wheelock's school at a perilous moment.

In the past two years, its enrollment dipped by nearly 30 percent — to barely 1,000 undergraduate and graduate students. Only about half of its students left with a degree. And the school's endowment shed almost a third of its value in the recession, and it still hasn't returned to its 2007 heights.

As an educator, Chard says he's used to being strapped for cash: "Listen, when I started teaching in the 1980s, we were counting the number of photocopies we made, because we couldn't afford paper. So that has been part of my life for a long time."

Still, the college has had to try to raise revenue. Of late, it has accepted nearly all who apply, and charges thousands of dollars more in annual tuition. (It's worth noting that, for the average student, Wheelock is still about $10,000 per year cheaper than Boston University.)

That spiral — of rising costs and shrinking enrollment — is common at small colleges colleges across the country.

Michael Horn, an education consultant based in Boston and co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, puts it this way: pit "significant increases in tuition, year over year over year, against the reality that middle-class wages have largely been stagnant."

Horn anticipates that many such schools could end up merging, closing or going bankrupt in the years ahead. "Forty percent of colleges in this country have fewer than 1,000 students — I think all of those are at grave risk," he warns.

But Wheelock is further hampered by the purity of its mission. No one wants to see their alma mater disappear. But some schools train doctors or lawyers who might shore up its endowment with donations — Wheelock trains preschool teachers and social workers.

Mounting research suggests that high-quality, early-childhood education is just as important to a child's development as it seemed to Lucy Wheelock a century ago. But its practitioners aren't paid very much; American preschool teachers, for example, earn a median salary of just $28,700. That means the average Wheelock graduate leaves the school carrying what could be almost a year's salary in student debt.

Making good on Wheelock's promise to its founder, and its current students, meant making a change, Chard said. First they sold off the multimillion-dollar Brookline house reserved for the college's president; Chard and his partner had been living there. Then they quietly asked larger schools across the country to consider a partnership.

And this week, Wheelock and BU announced they were in talks to merge.

Chard says BU felt like a natural complement. Wheelock's program focuses on clinical training for teachers, while BU's school of education excels at research. And the two campuses are less than a mile apart.

"If you put those two together, we have the potential to create a preeminent college of education and human development in New England," he says.

Many of the details of the prospective merger remain unclear. BU refused to comment, but its president, Robert Brown, said in a letter to students and faculty:

Over the coming weeks, we will be working with our faculty and our academic and administrative leaders and with the leadership of Wheelock College to shape the vision of our merged academic units and services. We believe the merger will lead to enhancement of our programs, while also maintaining the exemplary mission of Wheelock College.

For his part, Chard imagines a new school that would combine the two faculties, continue to train teachers, and bear the Wheelock name. If the plan proceeds, current Wheelock students would be admitted into BU.

Many current Wheelock students say they're still processing the news and aren't ready to express an opinion. But many say they're relieved.

Like Tim Konowski, a rising senior in Wheelock's special education program, who says he's glad that a school he's loved has a new lease on life.

"Not being sure if I was going to be able to take my own family there in the future, because it would be, like, a Stop & Shop at the end of the day — it makes me really happy," Konowski says.

It feels like a happy ending to Chard, too, after an uncertain first year on the job. The merger hasn't gone through yet, but Chard hopes that if it does, he'll have done right by Miss Wheelock's vision.

"I hope that I'm not doing her a disservice, but really I'm helping her legacy live on."

This segment aired on August 31, 2017.