Advertisement

When It Comes To Teaching English, Beacon Hill Says One Size Doesn't Fit All

Resume

After several attempts, Massachusetts lawmakers have all but confessed there may be no single right way to teach English to students who don't already know it.

A compromise version of the LOOK Act — short for "Language Opportunities for Our Kids" — has sailed through both chambers of Beacon Hill Wednesday and will be heading to Gov. Charlie Baker's desk. The bill would allow school districts to decide whether and when to use students' native languages, or a dual-language approach, as they build English proficiency.

The latest change would come after decades of experimenting with two one-size-fits-all approaches to English-language learning.

In 1971, Massachusetts became the first state to pass bilingual education into law, under a system that used students' native languages to teach them math and history, as well as English.

But over time, some critics argued the state's approach tended to strand students in their native language. Like Lincoln Tamayo, who told WBUR that as a school principal in Chelsea, he saw firsthand how that bilingual approach failed.

And that's why he quit that job and became the face of a 2002 ballot campaign to adopt a new curriculum where students learn and speak almost entirely in English.

The curriculum, known as "sheltered English immersion" (SEI), had by then been adopted in California and Arizona. In Massachusetts, it won allies like Mitt Romney, who was then running for governor.

At a debate that year, Romney cited statistics showing students learned English more quickly in SEI classrooms. Massachusetts voters agreed with Romney's argument, and passed the measure by a 2-to-1 margin.

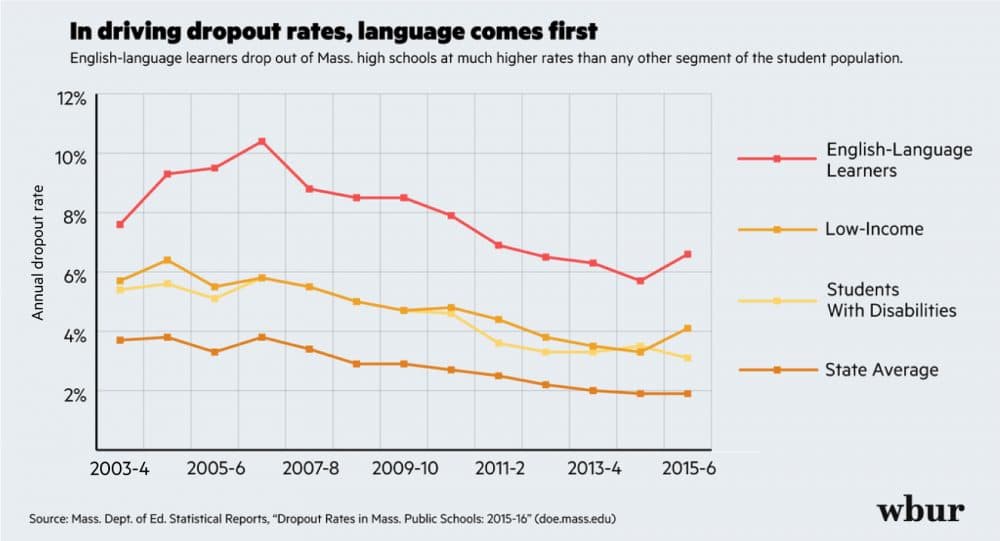

That was 15 years ago. Today, the state isn't seeing that promised progress. Students in immersion can take many years to learn English. And English learners drop out of high school more than any other group.

This summer, both houses of the state Legislature voted overwhelmingly in favor of reform.

State Sen. Sal DiDomenico sponsored the Senate version of the bill. DiDomenico grew up in Cambridge under bilingual education, and he says many of his classmates thrived. But, he notes, this new bill isn't simply a lurch back to that older model: now "there's better tools, better instruction — and people now have a better sense of how to teach in this model."

What's more, DiDomenico says, districts that want to retain an immersion approach can do so, though all districts will have to submit their plans to the state board of education.

DiDomenico says that the bill may help undo stigma as it prepares students for a future outside the classroom: "Many industries are looking for bilingual employees. Being bilingual is an asset — it's a benefit to the success of our children." Toward that end, the bill establishes a "state seal of biliteracy," a commendation given to students who can read and write in more than one language.

It's a sign, he says, of how much last 15 years have changed minds about what a second language can mean.

This article was originally published on November 15, 2017.

This segment aired on November 15, 2017.