Advertisement

Funding Complexities Remain For Mass. Drug Recovery High Schools

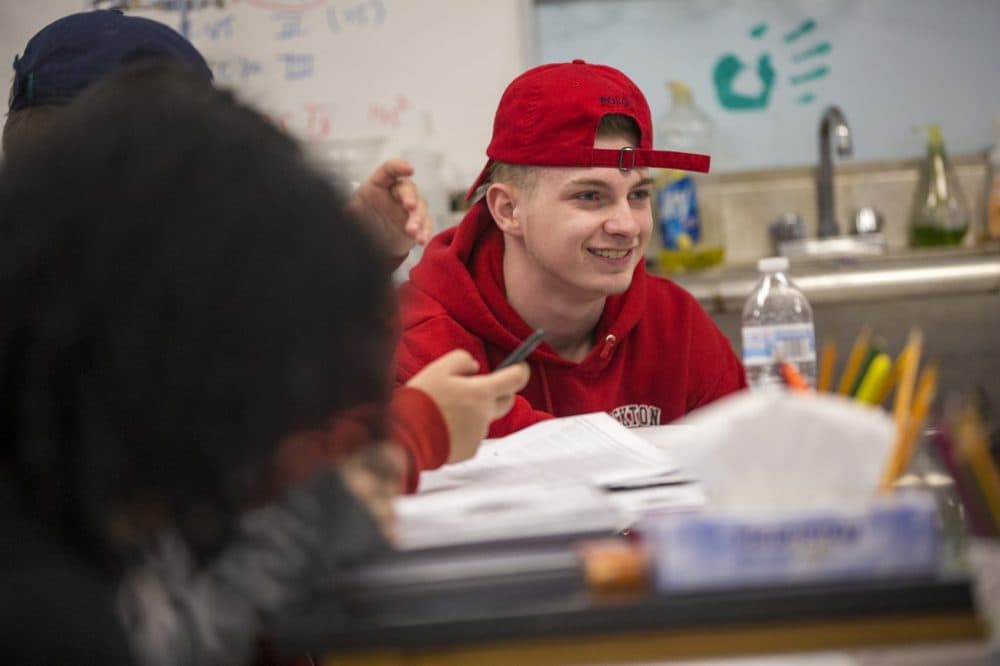

Riley McCabe has only been attending Independence Academy in Brockton for about three months, but he says he's already begun to feel like a new person.

"This is the best school I’ve been to," the 16-year-old said. "Before I came here, I was doing a lot of drugs, but now I have a place where I can be myself and be supported as I figure out what makes me, me, without any substances."

McCabe is one of about 200 students who attend five drug recovery high schools across the state. The schools, which help students working to overcome drug and alcohol addictions, are small, averaging only a few dozen students, and are therefore more expensive on a per-pupil basis. But researchers say the schools have taken on an increasing importance amid the opioid epidemic, as their sober environments can help set adolescents on the path to recovery at a crucial time in their lives.

As budget season kicks into high gear on Beacon Hill, the negotiations have turned a spotlight on the complexities of budgeting — and operating — drug recovery schools.

Advocates’ Case For Recovery Schools

That sober environment includes group therapy, 12-step meetings, drug testing and counseling. More than anything, supporters say drug recovery high schools give students the chance to recover while surrounded by an understanding peer group.

"A lot of our students are homeless or precariously housed, and this is a place they can call home," said Karin Burke-Lewis, Independence Academy’s recovery counselor. "These kids lose a lot of school because they’re in treatment, and they know no one will freak out and ask why they haven’t finished up their math homework if they relapsed. We’re able to give them a supportive place where people understand them, which is invaluable."

The schools were created more than 10 years ago. In addition to Brockton, they're located in Boston, Beverly, Springfield and Worcester, and serve students from surrounding communities.

"The opioid epidemic has created pockets of money and a demand from constituents that we need to be doing more to help adolescents with addiction, so recovery schools are something more states are turning to," said Vanderbilt professor Andy Finch, a leading researcher on recovery schools. "Many states look to Massachusetts as a model as this is something [the other states] turn to, largely because the original schools built so long ago are still around."

"These kids lose a lot of school because they’re in treatment, and they know no one will freak out and ask why they haven’t finished up their math homework if they relapsed."

Karin Burke-Lewis, Independence Academy’s recovery counselor

It’s tough to quantify what success means in a recovery high school. In a 2017 study, Finch found students at recovery schools were twice as likely to report abstinence from alcohol, marijuana and other drugs after six months than students who did not attend a recovery school.

Attendance can be spotty among students; they often need to leave for extended periods of time to go to addiction treatment centers. The schools are much smaller than public schools, which means they’re often more expensive to operate. Administrators struggle over whether to focus on the number of students who graduate, or the number who stay sober.

"Adolescent recovery is so complex and so all over the place; if people are looking for a straight line or how many kids relapse to quantify success, they don’t understand the nature of recovery," said Ryan Morgan, principal of Independence Academy. "I look at how many students we have who are engaged because that means we’re getting through to them."

In Brockton, the average Independence student stays 278 days, which includes time spent in summer programming. The school currently has two students who have attended for more than 1,000 days, or three years. Morgan says, in this way, recovery high schools are a form of long-term treatment.

Funding Ups And Downs

The schools currently receive state funding from the Department of Public Health, but, starting next school year, they will be overseen by the Department of Education. They also receive tuition dollars from school districts that send their students to recovery high schools, and some schools receive grants from mental health and substance abuse organizations.

In 2016, when he signed what he called "the most comprehensive measure in the country to combat opioid addiction," Gov. Charlie Baker fought back tears as he thanked the students at Northshore Recovery High School for sharing their “heartbreaking stories of addiction and loss.”

In a letter to them just days before he signed the legislation, Baker wrote, “There is no better case to be made for Recovery High Schools than the stories that you have bravely written and shared on Facebook."

In the fiscal years 2016 and 2017, the schools were allocated $3.1 million, with a line item saying that some of the money should be spent to open up a new recovery high school. This fiscal year, recovery schools were allocated $3.6 million, of which no "less than $500,000” was to be spent on a sixth recovery high school.

But under Baker’s new budget proposal for fiscal year 2019, which starts in July, recovery schools would receive $1.1 million less (there is no longer $500,000 allocated for a new school).

The Executive Office for Administration and Finance (A&F) said when the governor’s office made its budget appropriation for $2.475 million, in January, it based the number off the projected spending for the five schools for this current fiscal year, calling it level-funded.

But that $2.5 million figure doesn’t include one-time payments the administration has given out in recent years. The payments started three years ago, when leaders of the recovery high schools say they petitioned the governor to release funding allocated for the sixth recovery high school that has never been built.

“The amount of money proposed now [$2.5 million] is not going to be sufficient,” said Stephen Donovan, executive director of North River Collaborative, which oversees Independence Academy. “We need the money from the [one-time] payments just to keep the doors open. This allocation would put us in a situation where we have to consider whether we can afford to run the school long-term.”

Early last month, many leaders at recovery high schools feared for their survival. They posted on social media, testified at the House Ways and Means Committee about the importance of level funding based on all of the allocations they’ve received, and put in calls to the governor’s office.

Now, many school leaders told WBUR they’re optimistic they’ll see more funding due to conversations with the administration and with House legislators, who are releasing their budget this week.

"We’re grateful the governor released more funding earlier this year," Independence principal Morgan said, speaking of the $600,000 one-time payment the state doled out to the five schools earlier this year. "It pulled us out of a hole. Hopefully we’re able to keep working with the administration to address the needs of recovery high schools."

How Funding Impacts Operations

The school uses, and needs, every extra dollar it receives, Morgan said. In fiscal year 2016, for example, Independence received about $120,000 from a one-time payout from the state.

He can trace the direct impact. When Morgan was a first-year principal, in 2014, more than a few times he walked through the doors and found only one student had shown up to school. There were only about 10 kids total enrolled.

When it received the additional funding two years ago, Independence spent it all on transportation to get students to school.

Once Independence advertised in April 2016 that it could transport students to the school, Morgan says enrollment jumped. That month, the school received 11 referrals for new students -- about half of what they’d received in all of the seven months prior. The school serves the entire southeastern region of the state, and the average student travels 40 miles round-trip to attend school each day. The school now has about 35 students in attendance.

“Once referrals increased, it was then clear to us that transportation was the big stumbling block to enrollment,” Morgan said. “Once we could get students there, we could help provide the services they need.”

The schools also receive money from districts to send students to recovery high schools in their community. While districts pay an average of $15,000 per student to educate students in their own districts, they pay an average of $11,000 per student sent to a recovery high school, leaving a deficit that recovery schools have to make up.

On top of that, it costs much more than $11,000 to educate students at recovery high schools.

Fran Rosenberg, executive director of the Northshore Education Consortium, which oversees Northshore Recovery High School in Beverly, estimated it costs about $35,000 to educate each student. That cost includes individual and group counseling, as well as substance abuse treatment for students.

For comparison, at Northshore Academy Upper School, a special education therapeutic high school that’s also run by the consortium, public districts in the region pay about $40,000 for students to attend, Rosenberg said. Students with learning disabilities are protected under federal law, and school districts are required to provide special education services to these students to accommodate both their educational and mental health needs. But districts aren’t required to provide special services for students' substance abuse disorders.

Although the state is required to transport students with special education needs, they are not required to transport students solely on the basis of their substance abuse disorders.

Despite an infusion of state money earlier this year, Rosenberg said the school will finish the year with a deficit of $95,000.

The governor’s budget is a proposal, and not set in stone. A&F said the administration will work with the Legislature throughout the budget process to ensure recovery high schools have adequate funding in the final fiscal year 2019 budget.

"We are grateful for the Governor's support of Recovery High Schools and hope to continue to work with his office, DPH, and DESE to solve the issues related to sustainable funding and transportation so that students who need our schools are able to access them regardless of geography or family status," Rosenberg said in an email.

Students at the recovery high schools stress their importance, and how they provide environments to recover that are removed from the triggers at their original high schools. Dasia Ambers, 18, has attended Independence for about a year and said it’s more than a school to her.

"I didn’t even have classes today, but I was feeling anxious so I stopped by," she said last month. "This place is like a home. I don’t know where I’d be without it. Everyone deserves to get better, which Independence has shown me."