Advertisement

The Vault

Resume

How good are you at keeping secrets? Do you blab immediately, or do you have a Seinfeld-esque Vault?

Of course, that’s not an actual vault — more of a metaphorical one.

This week on Endless Thread, we talk about a real vault, one that holds not only secrets, but actual valuables as well. The contents don’t glitter or shine or pay for anything, but they are probably the most valuable items in the world.

The vault in question is located far north, up in a Norwegian archipelago called Svalbard. Svalbard is almost like the end of the Earth — it’s a remote place with reindeer, Arctic foxes and about 2,500 humans.

Built into the side of the mountain, the vault holds seeds: seeds for every edible plant you can think of. Three thousand varieties of coconuts. Thirty-five thousand varieties of corn. Two hundred thousand varieties of rice. Kind of a Noah’s Ark of seeds.

It’s called the Crop Trust, and it’s meant to be a backup for humanity if… when?... things go wrong. We stumbled across this story while browsing one of the most popular subreddits, /r/todayilearned.

For each crop, there’s an envelope with 500 seeds, says Marie Haga, executive director of the Crop Trust. Any nation can store seeds in the vault for free, making the vault a sort of world peace zone. South Korea’s seeds sit next to North Korea’s. Ukraine’s are right next to Russia’s.

Protecting our food supply is probably the one thing the whole world can get behind. If the Big One happens, we’ll want to grow food again, right?

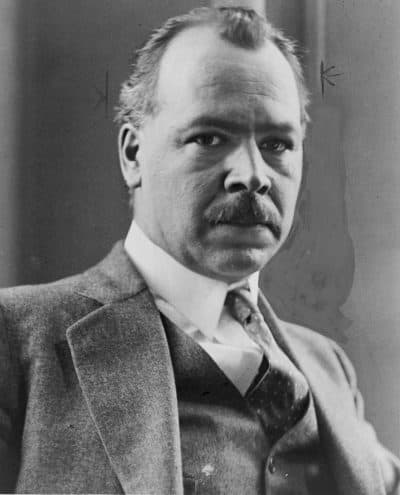

The vault's origins start with one man, during World War II — a global existential crisis if ever there was one. His name was Nikolay Vavilov and he lived in what was then the Soviet Union.

“I don’t know what the Crop Trust would have been without Vavilov,” says Haga. “He really explained why we are fully interdependent when it comes to crops.”

To get some background on Vavilov, Amory and Ben spoke to Gary Nabhan, an agricultural ecologist ethnobotanist, Franciscan brother and author of Where Our Food Comes From: Retracing Nikolay Vavilov’s Quest to End Famine.

Vavilov grew up during some intense famines in eastern Europe, and he was determined to never let them happen again, says Nabhan.

As Vavilov began his work as a botanist during the 1920s, he developed an idea: maybe collecting the seeds, and understanding how crop diversity across the world works, could help to fight off crop failures and to prevent famines.

It was a revolutionary idea, says Nabhan.

"Vavilov was the first one who had the education in what we would call evolutionary biology, how plants adapt to different climates and conditions, and could apply that to plant breeding and disease resistance in crops," says Nabhan. "He had this sort of humanitarian set of values that underscored the way he did science."

Vavilov and a team began gathering hundreds of thousands of different kinds of seeds from 64 countries, more than 100 expeditions in all.

But he was not without his detractors. A former student, Trofim Lysnenko, got Vavilov arrested and thrown into a gulag in Leningrad (which is now St. Petersburg). And though nobody, including his family, knew where he was, his group carried on.

The siege of Leningrad lasted almost two and a half years. More than 1 million people died — half of them from starvation alone, says Nabhan.

And yet, Vavilov's team continued his mission. Even when they were starving. Even when the seeds they were protecting could have saved their lives.

"A rice collector named Dimitri Ivanoff... died within just a few feet of a thousand packets of rice that, just by boiling up water and cooking, the rice could have saved his life....This is unparalleled altruism compared to selfish thinking," says Nabhan.

In total, 12 scientists died protecting the seeds. Vavilov himself starved to death in prison.

But the seeds survived. The Svalbard vault is a direct descendant, and the building in St. Petersburg where Vavilov first began his work is now the Vavilov Institute Of Plant Industry.

And just like Vavilov, Haga finds her work to be of the utmost importance.

"I consider it a great privilege to work on something so fundamentally important as safeguarding the diversity of crops," she says. "That job is really about safeguarding the basis for our food. Then, now, tomorrow and forever."

Thanks to /u/milksperfect for this week's featured art.