Advertisement

The GOAT

Resume

I am not much of a sports person. I am fairly athletic but clumsy — I broke my arm ice skating, I sprained my ankle playing soccer and I tore my ACL while skiing.

And while I'll never say no to some tickets at Fenway (that's meghan AT bu dot edu), I don't really watch many sports, either.

But even I, as a sports n00b, understand what the phrase "The Babe Ruth of X" means. Or as the kids today say, the GOAT — Greatest Of All Time.

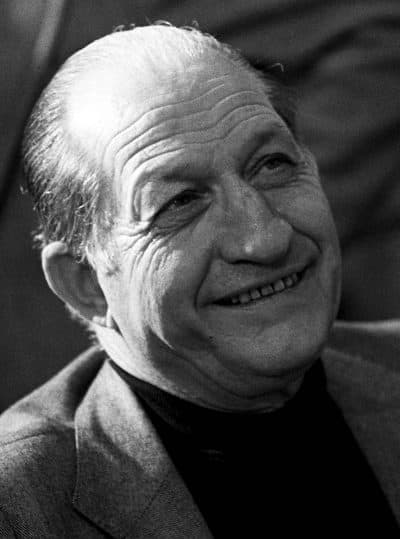

This week, we focus on a GOAT you may have never heard of, an Italian man named Gino Bartali.

Bartali was a famous Italian cyclist, who competed in the Tour de France in 1938 and 1948.

And he lived a bit of a double life, involving the Catholic Church, secret missions, Jewish refugees and a robust fake ID operation.

Bartali's story surfaced on Reddit one day, when u/EtOHMartini was looking online for a Mario Batali cookbook, but accidentally added an "R" in the middle of Batali's last name.

EtOHMartini posted on r/TIL about what he found:

TIL of Gino Bartali - champion Italian cyclist. During WWII, he cycled through Italy carrying messages for the Italian Resistance. from r/todayilearned

Amory and Ben, intrigued, reached out to Aili McConnon, who co-authored a book about Bartali called "Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, the Nazis and the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation."

She first began researching Bartali when she found a mention of him in an Italian newspaper about his work helping Jewish refugees during World War II.

"I thought, huh, a cyclist helped the Jews. I wonder how he did that. And as we did a bit more digging, we discovered, not only had he helped the Jewish community, but he'd used his bicycle to do so," says McConnon.

And he did all this while walking around as a famous guy, a household name, the champion of the Tour de France of 1938.

"Bartali, at the time, was kind of the Babe Ruth and Clark Gable of Italy rolled into one," says Oren Jacoby, who made the documentary "My Italian Secret" about Bartali and other Italians who helped Jewish refugees escape the Nazis during World War II.

Aili McConnon explains that, in 1943, when the Nazis came to Italy, a large community of Jews had fled to Florence, where the rabbi there turned to the cardinal of Florence.

And the cardinal, says Jacoby, turned to Bartali and asked for help to smuggle the Jews out of the country via monasteries.

So, Bartali gets on his bicycle, and becomes a de facto bike messenger for a network that ran between Florence and Assisi — about 110 miles apart — which helped refugees get fake papers. He would collect photos of the refugees from the monasteries and safe houses where they were taking shelter. And then he'd bike the photos to a father/son team in Assisi, who were printers and could make actual fake identity papers that the photos would be attached to.

"Bartali was a great person to participate in this secret network in this way because he was one of the few people during the war years who had relative liberty to move around," says McConnon. "He still trained on his bicycle, so he could be seen in the countryside in Tuscany and Umbria."

And if he got stopped, well, he could just say he was training for his next race. He hid the fake papers and photographs in the bike frame, the tube, underneath the seat and in the handlebars.

This was risky, of course. He was married and had a young son, says McConnon.

"His diaries from the wartime years, he discusses how difficult it was to sleep, and basically, that he was on edge and highly, highly anxious for much of that period," says McConnon.

His family knew some of what he was doing, as he was also hiding a Jewish family in his house. But they didn't know the full extent.

Near the end of the war, someone tipped off the authorities and Bartali was brought before the secret police, who knew something was up, even if they didn't know what.

The secret police headquarters was not a pleasant place, say Jacoby and McConnon. Prisoners were tortured in plain view and Bartali sat there for three days, watching people get their teeth pulled out or hot liquid forced down their throats.

"But after three days, when they took him out to question him, one of the aides to the head of the secret police said, 'Look, I can vouch for this man. If he says he hasn't done anything wrong, you should let him go,'" says Jacoby.

Bartali was released.

It wasn't until his older son, Andrea, was in his 30s that Bartali told him any of this. It stayed a secret to everyone else almost until he died, in 2000.

Oren Jacoby's documentary includes archival footage from 1985 of Bartali saying in Italian, "I don't want to talk about it or act like a hero. Heroes are those who died, who were injured, who spend many months in prison."

He's estimated to have helped at least 800 Jews escape the Nazis.

And then, in the post-war years when Italy was struggling, Bartali went and helped again — by winning the Tour de France in 1948.

"It was very much seen as being quite important in terms of improving the mood in Italy at the time," says Aili McConnon. "I think one historian said he gave the country back its smile."

Bartali's actions may have remained relatively unknown for most of his adult life, but not for long. This year, the Giro d'Italia, Italy's famous annual cycling race, is starting in Jerusalem, to honor Bartali's work for the Jewish community during World War II.

His granddaughter, Lisa Bartali, with some help from WBUR staffer Jamie Bologna, talked to Ben and Amory about her grandfather. She is also an avid cyclist and runs a blog called Biciclettami.

"He never really talked about his history or his story. He was very reserved in character," says Lisa, in Italian, of her grandfather.

She sees this year's Giro d'Italia as a great way to honor her grandfather on a global scale, and hopes it will introduce her grandfather to a younger generation so others will be inspired to follow his example.

"It didn't matter the race or the religion of the people," Lisa says, in Italian. "He was against people who were violent and he was against the oppressors... He saved anyone who was in threat for their lives."

Grazie to our colleague, Jamie Bologna!

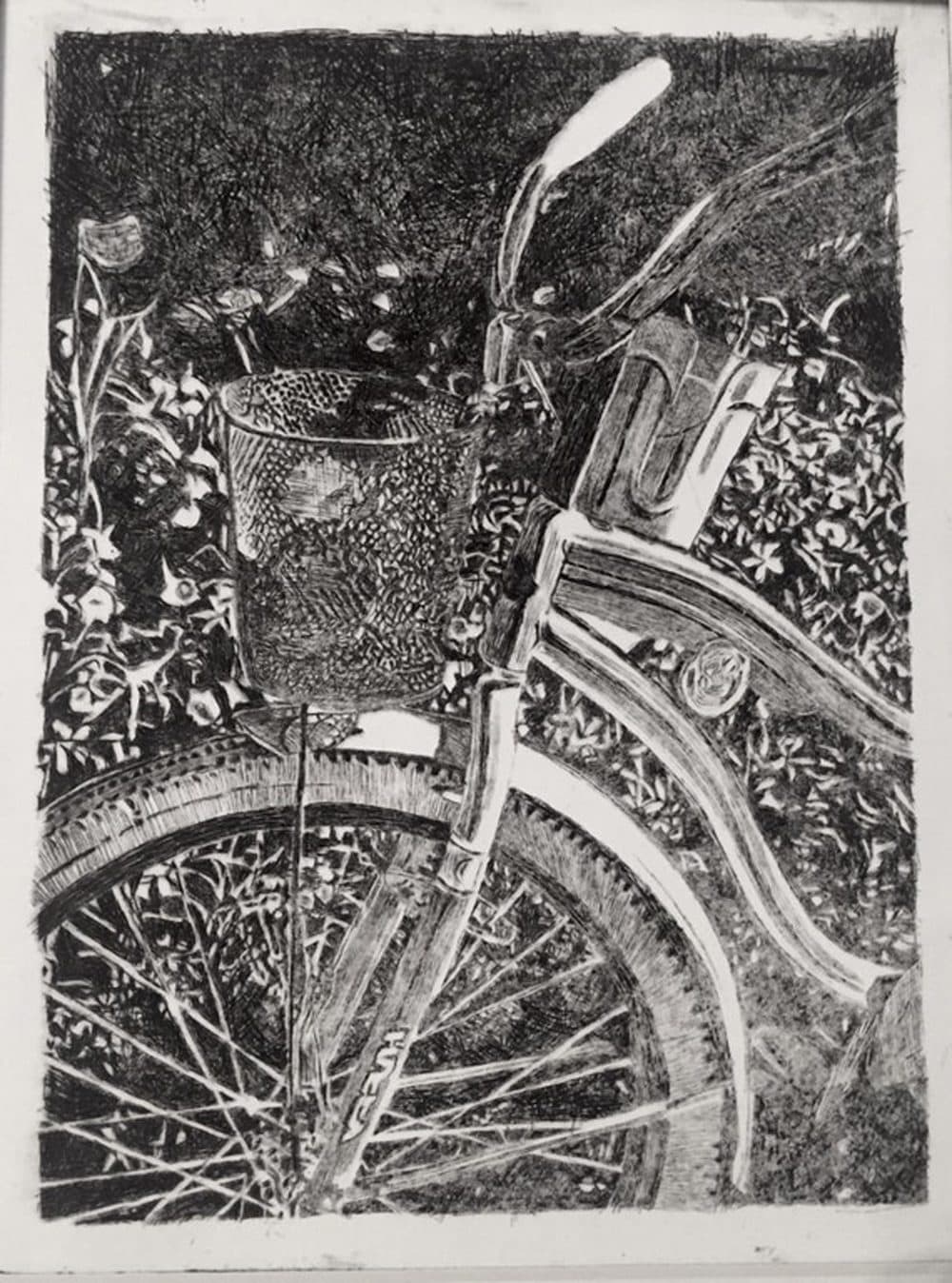

And thanks to u/leahmarie315 for letting us use her artwork for this week's episode. Follow her on Instagram HERE.

You can find us on Twitter at @endless_thread and on Reddit as /u/endless_thread. Subscribe to the podcast with Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, RadioPublic or RSS.