Advertisement

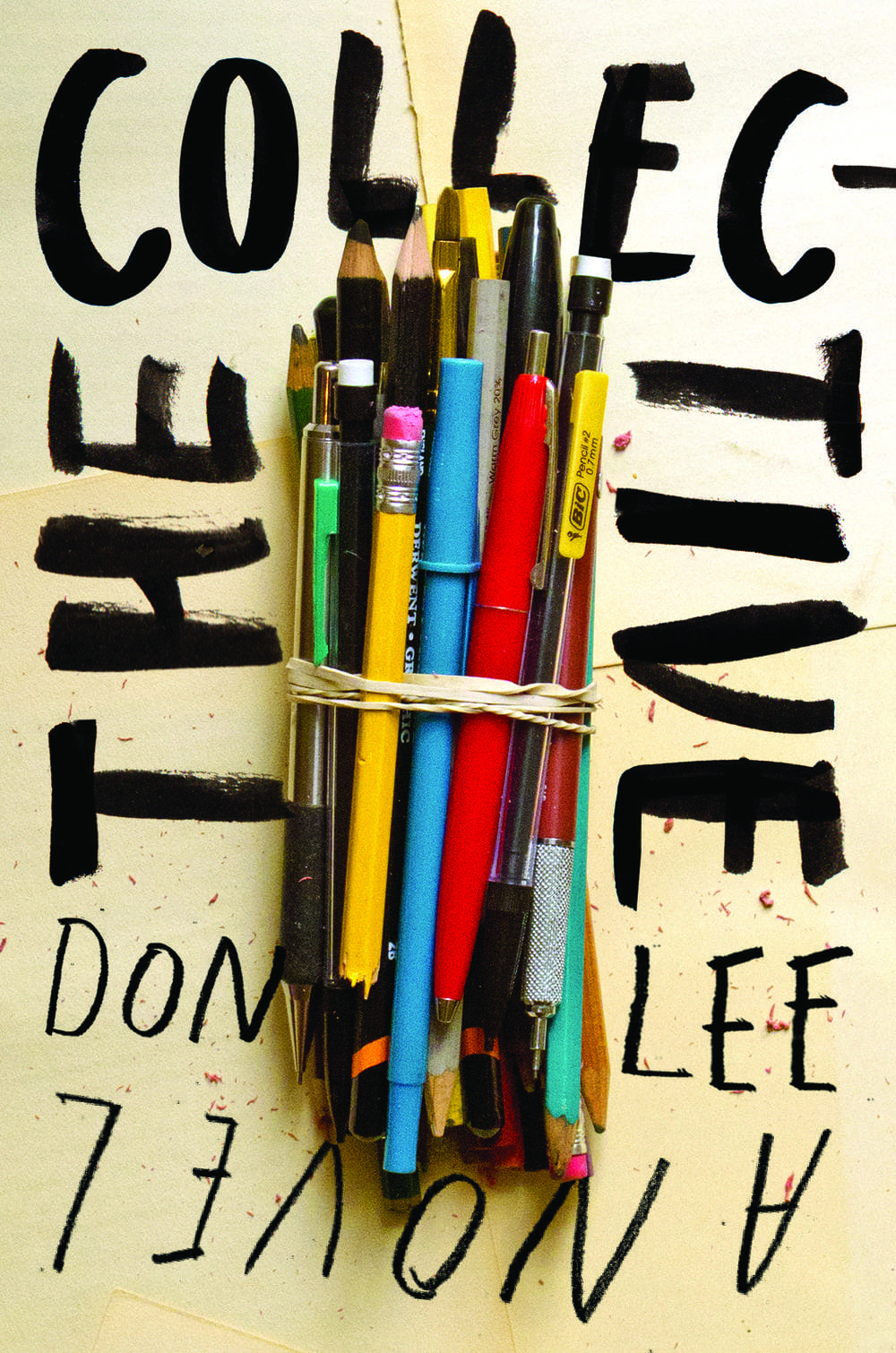

Author Don Lee Addresses The Young Asian American Experience

Resume

If you're Asian-American, have you suffered stupid questions like: What's a good place to eat in Chinatown? Do you know Kung Fu? Do you eat dog meat? The perceptions, stereotypes and realities of three Asian-Americans play out in Don Lee's new novel, "The Collective." Here & Now's Robin Young sat down with Lee, part of the conversation is transcribed below, followed by an excerpt from the book.

- Harvard Book Store: Don Lee Reading Tuesday, July 24

In your book, Eric, Joshua and Jessica all meet at a small liberal arts college in Minnesota. Eric, an aspiring author, Jessica, an artist, Joshua, a writer. All three of your characters are considered Asian American by others looking at them, but in fact they are very different.

Yeah, it's a strange and really broad rubric, especially these days when you include South Asians, Indians, and Pakistanis as well. It's an odd category, and I think that it is one that's probably too broad.

Eric is third generation Korean American. He grew up in Mission Viejo and thinks of himself as American. Joshua was abandoned at a Korean orphanage and adopted by Massachusetts intellectuals. Jessica is a second generation Taiwanese who wants to be an artist. There are similarities in the way the world sees them but many differences in who they are.

I think that its something that most people who aren't Asian American don't really recognize in terms of generational differences. I'm third generation Korean American and mostly from California, although my father was in the state department, so I bounced around a lot oversees as a kid. But really didn't think about my ethnicity until I moved to Boston back in 1984 to attend graduate school at Emerson College. It was only here that my questions about identity really arose, because here it seemed there was a kind of segregation in terms of race. People did actually say things to me. I had these encounters that were shocking to me.

Like what?

Just walking through a crowd of people, there were a bunch of guys and one of them said to me, directly to my face he said, "Did you know it's National Hate Chinese Week?" Things like that happen, and coming from California, where you have so many Asian Americans, you know, I never expected that.

So that goes to some of the racism that the characters see and feel. But what about who gets to write about race? When they're in this school in Minnesota, Joshua excoriates a young white woman because she wrote a story based in China. "You can't write about the Asian experience unless you are Asian," he says. What are you saying about who gets to write the story?

I think issue of cultural appropriation, in terms of writing, is very interesting. It's one that's heatedly debated. Here, I'm more interested in what's happening within Asian American writers and artists. And I think when we're going through this transitional period, and we're all asking ourselves several questions. You know, if you're an Asian American writer, do you always have to have race as your subject? Do you have to have all your characters Asian American? If you don't, is that race betrayal? I mean, if you keep on doing that, are you limiting yourself, are you ghettoizing yourself and your audience, or even perpetuating stereotypes? And so these are, you know, the arguments that they have within the collective here.

You're right in the middle of that debate because you're writing a book that's filled with Asian American characters. Is that what you think you should do?

From a personal point of view, I think that we should be able to do anything that we want to. And, actually, I think that that carries through as well to white writers. If they want to write from a different race's point of view, that's fine with me too.

And I've written stories about a chair maker, a sculptor. I'm not a chair maker or sculptor, but I believe if I do enough research and am true to those characters, then I have a right to do that. But there are many people who would adamantly disagree with that.

Book Excerpt: 'The Collective'

By: Don Lee

There’s a road in Sudbury, on the outskirts of Boston, called Waterborne. Famous for the great blue herons that nest there, the road cuts through the immediate floodplain of the Sudbury River. It’s lined with red maple, white oak, and dead ash yellows, long ago decimated by a virus. It curves and dips, wending through hills and an alluvial marsh, rising once again past meadows and farmland, then descending in a series of hairpin turns. It’s a beautiful road—smooth, continuous, unsullied by houses or businesses—and therefore popular with bikers, runners, and drivers in a hurry. To no one’s surprise, hardly a month goes by without some sort of accident on Waterborne.

It was around three o’clock on a Saturday afternoon in late September 2008, partly cloudy and unseasonably warm at seventy-six degrees, the tincture of fall edging the flora. Joshua Yoon, thirty-eight, was on his afternoon run on Waterborne, hugging the road’s left edge so he could watch for approaching cars. He had intended nothing for that day. The week before, in fact, he had arrived upon the method he’d use, suggested by a group on the Internet: he was going to put a clear plastic bag over his head, fasten the bottom of it around his neck with Velcro, open two canisters that would pump helium through tubes into the bag, and within minutes he would be unconscious and dead. Painless, quick, and efficient.

Once you decide to kill yourself, studies have said, there is clarity. You become focused. Your mood brightens. You’re blessed with a profound state of well-being. These sorts of decisions, momentous as they are, come willy-nilly. They begin as passing whims, an indulgence of reverie, and then, unbidden, they sharpen and coalesce within you, and you begin to fixate, and plan. You pay your bills, you write letters of instruction, you update your will, make funeral arrangements, buy an urn, label all your keys. There are only two things left to be determined—how and when. You have choices. You feel relief and joy.

This is not to say that Joshua was entirely lucid then. He was taking pills, so many pills. He was on antidepressants, anti-anxiety meds, mood stabilizers, sleeping pills, and painkillers, their effects aggravated by a recent experiment with robostripping, something he’d learned teenagers were doing, spinning a bottle of Robitussin centrifugally on a string to distill pure DXM to the top. He was high, perhaps even hallucinating—not that it mitigates anything.

He was running on a stretch of Waterborne where drivers are slingshot out of a curve and accelerate. He heard a car coming, and, rather than keeping to the edge of the road, he drifted a few feet onto it.

Did he really mean to do it, to be hit by someone and killed? Could he have been so callous, willing to burden an anonymous driver, through no fault of his own, with a lifetime of trauma?

To this day, I am not sure. I go over and over it, and still I don’t know. Maybe Joshua, my old friend, had only wanted to feel the whoosh and rev of the car as it went by, the inches between death and continuance, how arbitrary the sway can be between the two. Maybe he had yawed drunkenly into the car’s path without volition or meditation. Yet the impulse had probably come across Joshua before, more than once, running on that road, to step in front of a speeding car, ending everything right then and there. Whatever the case, there was a witness, a driver approaching from the other direction, who claimed she saw Joshua veer abruptly and unmistakably into the path of the car.

The timing of it, the multiple, trivial interruptions that could have prevented any of it from happening: a stoplight, a phone call, a detour for ice cream, a playmate needing a ride home. A few seconds would have made all the difference.

A few seconds before the car came out of the turn, the little girl in the backseat, three months shy of her fourth birthday, had unbuckled herself and climbed out of her safety chair to pick up a book she had dropped. Her father was driving too fast, a bit impaired himself, having had a few drinks earlier at lunch. He disliked seat belts and would have eschewed them altogether if not for the insistent warning beeps. That day, he had compromised by clicking in the lap belt and flipping the shoulder strap behind his back. He turned around to yell at the girl to get back in her chair right this minute. Then he glanced around and saw Joshua, ten feet in front of him on the road, too late to do anything, but swerving on instinct to avoid hitting him head-on. The car swiped out Joshua’s legs at an angle, crushing one of them and snagging the other on something, maybe the bumper, so his foot disarticulated at the ankle, much like twisting a chicken bone off at the joint. The impact vaulted his body into the air in deranged cartwheels, and the car itself flipped and rolled in the other direction, tumbling repeatedly and brutally, until it squashed to a rest against a stand of white oak. By then, the man and the little girl were slowly dying inside the car. Joshua was luckier, if one could call it that. He landed on his head on the asphalt, and the blunt-force trauma to his brain killed him instantly.

Copyright W. W. Norton & Company (July 16, 2012)

Guest:

- Don Lee, author

This segment aired on July 24, 2012.