Advertisement

A Chance Encounter, A Life-Changing Friendship

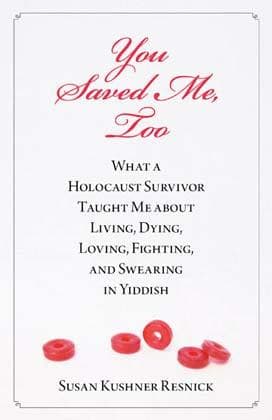

What began as a chance encounter between an aging Holocaust survivor and a young mother developed into a 15-year-long relationship that both credit with changing, if not saving, each other's life.The relationship is chronicled in Susan Kushner Resnick's new memoir, "You Saved Me, Too: What a Holocaust Survivor Taught Me About Living, Dying, Fighting, Loving, and Swearing in Yiddish."

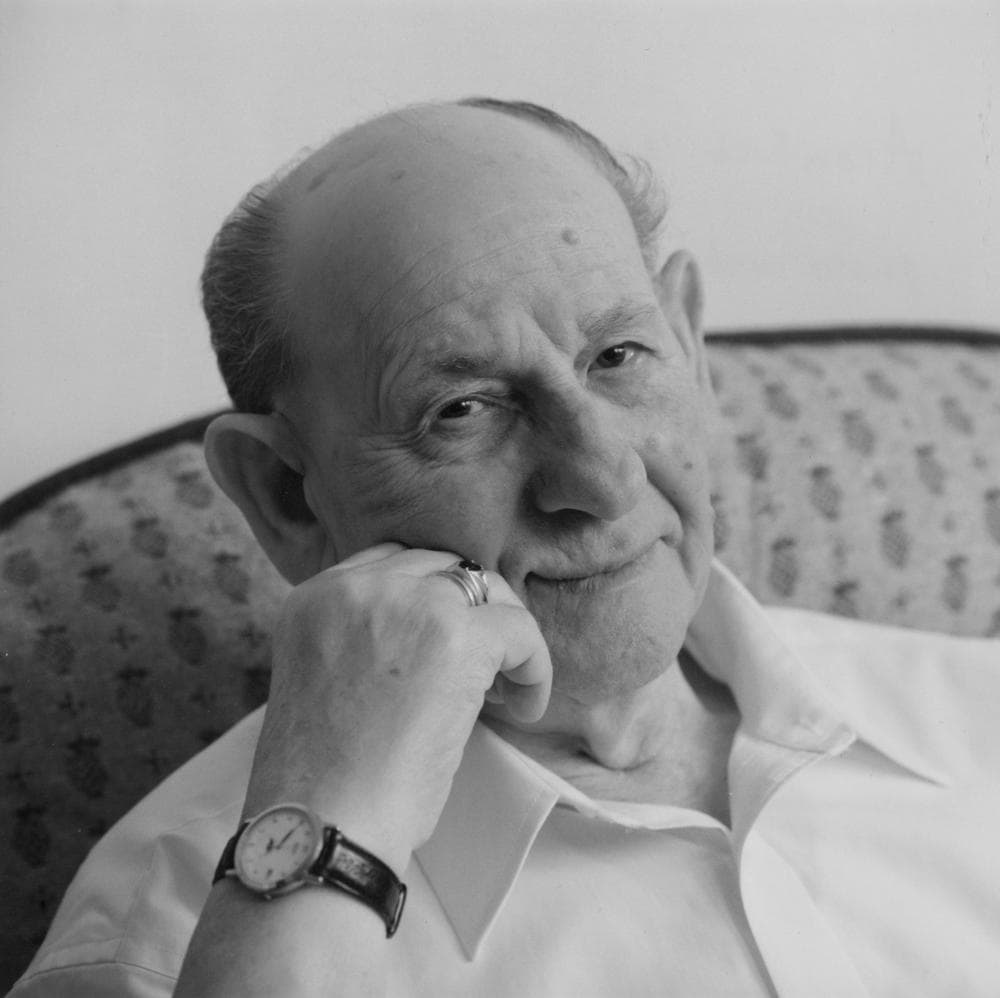

Kushner writes the book in the form of letters to her now-deceased friend, Aron Lieb, and others. The letters detail not only Kushner and Lieb's intense, funny and unusual relationship, but also the horrors he experienced during the Holocaust, his family history and the efforts Resnick made to help him die a good death after living a painful life.

In the shortest letter in the book, Resnick writes to Adolf Hitler.

"Dear Adolf,

This morning Aron Lieb, graduate of Auschwitz, who your staff left to die in Dachau in April of 1945, turned ninety one years old. You lose.

Regards, Sue."

Book Excerpt: 'You Saved Me, Too'

by Susan Kushner Resnick

You picked me up—let’s not forget that. I wasn’t looking for love on that bright and boring August day. I was just trying to hang on to my mind, which at that point was like a wet bar of soap. I’d get it and lose it and get it and lose it.I’d been swimming laps just before we met. It was one of my less successful strategies for clearing up a nasty case of postpartum depression.

Every other day I’d drop Carrie at preschool and then drive from our bucolic town to the seedy city down the road, incongruous home to a posh Jewish Community Center. While Max delighted women in the babysitting room—an innate flirt, like you—I slapped the water, as if I could beat the misery out of my muscles and leave it behind like dirt from under my fingernails. I was balancing Max on one shoulder while an empty car seat dangled from my arm when you noticed us.My hair was still wet. You waited until I’d started to thread Max’s arms under his car-seat straps before approaching.

“Vhat’s his name?” you asked.

I turned, summed you up as harmless, and answered.“Max.”“Hey, Maxeleh,” you said, your voice pitching higher. “What are you doing, Maxeleh?”You seemed to really like kids, which is why I asked if you had any grandchildren. I figured you were seeking out strange babies because yours lived far away and you missed them.

Advertisement

No grandchildren, you told me. No children, either. And your wife had died four years earlier.

“She killed herself,” you said.

Comedic beat. Wait for it.

“With chocolate.”

Okay, not exactly, you explained. She had diabetes and wouldn’t eat right. Your eyes twinkled when you saw me grasp the chocolate joke.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

It was time for me to go, but I wanted to keep talking to you. I was lonely and weak, but at that moment in time, you weren’t.

“Poland.”

“How long have you lived here?”“Since 1949,” you said, smiling down at Max. “After the war.”

“You fought in the war?” I asked, stupidly.

“I was in the camps. All the camps.”

All the camps. Maybe that wasn’t completely true, but close enough. You’d lived in the Big House, the Yankee Stadium of camps, the White House of camps, the Taj Mahal of camps: Auschwitz. It was there that you became a number, as did everyone else who passed under the work-will-set-you-free banner and avoided the introductory gassing. I didn’t realize until recently that Auschwitz inmates were the only ones tattooed. I’d thought they’d inked all of you. Now whenever I see someone with a Nazi-designed string of digits on their arm, I wonder if they knew you—if they crossed your path, shared your

bunk, tried to steal your shoes.

Auschwitz was more of a stopover than a destination for you.

Same with Dachau. You settled in longer at Birkenau, Auschwitz’s sister property, but they were always moving you someplace. You resided in so many slave-labor camps that you can’t remember all their names, and I will never be able to track your moves with journalistic accuracy. It will turn out to be easier to track your little sisters and the rest of your family because they traveled to death in a pack. But I knew none of this at our first meeting. Before you could dole out more hints, Vera arrived from the locker room. She’d been chlorinating herself in the pool, too. She had her stern Soviet face on, a face that said Who the hell is this chick, and why is she talking to my man? A biker’s face.

You introduced me to your girlfriend, but when did we introduce ourselves to each other? I’ve rewound that morning countless times, but an exchange of names never plays. Maybe, as Max would later observe, it wasn’t necessary. Maybe we already knew each other and you recognized us. Could you have been keeping an eye out for us before we were even born?

We walked out together and you two stopped to talk to another white-haired couple. I headed to my car, buckled Max in, and stalled in the driver’s seat until you came close enough to hear me. I loved your contrast: so cheery for a Holocaust survivor. Nothing like the tragic heroes I’d read about or seen in movies. They never seemed to laugh, as if that ability had been starved out of them. You laughed more than I did. I wanted to know more.

I beckoned you over.

“Do you want to meet for coffee someday?” I asked.

“You buying?” you said, with the twinkly eyes again.

So I guess maybe I picked you up.

We decided on the following Friday. All week I worried that you’d stand me up. Why would this stranger want to hang with me? I knew I’d feel like an idiot if you didn’t show, and inexplicably

sad, too.

You weren’t at the row of lobby chairs where the old men roosted while their wives exercised. I thought you’d blown me off; then I thought maybe I’d forgotten what you looked like and you were one of those dudes. But one was too fat and another had a mustache and none of them seemed to recognize me, so I kept walking. And there you were, a few yards down, all alone in your cap and glasses, waiting.

You waved and jumped out of your seat.

You showed. That day and every week after. And while we blew on our hot coffee, you began to tell me everything.

Guest:

- Susan Kushner Resnick, author

This segment aired on December 11, 2012.