Advertisement

Lessons From A Legendary Gardener

Resume

Rosemary Verey was the must-have garden adviser to the rich and famous, including Prince Charles and Elton John. And she was a celebrity in the U.S. as well.

Verey, who became renowned late in life, once said about a garden's life in the winter, "I love the garden in winter just always as much I do in the summer. I find it very satisfactory walking through and then each month, there's something slightly different."

Barbara Paul Robinson is a Manhattan lawyer - the first woman to head up the New York City Bar Association - and her love of gardening sort of snuck up on her.

She took a brief break from her professional life to observe legendary gardener Rosemary Verey at work at her home in the English countryside.

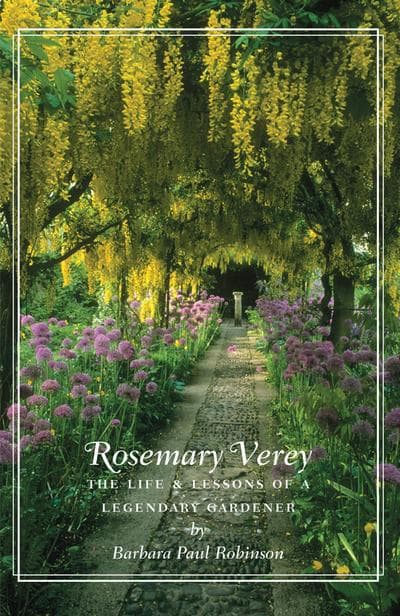

The book that resulted is "Rosemary Verey: The Life and Lessons of a Legendary Gardener." (See book excerpt below)

"One of her lessons is for everyone, not just gardening people, and that is her example coming to something quite late in her life and being self-taught and self-made and at the end of her life," Robinson told Here and Now. "She is world famous. Now, we might not all achieve that, but it is an inspiration that we can have an important chapter later in our lives."

Verey's first book came out in 1980 when she 62. She went on to write 17 more in 20 years, before she died in 2001.

Robinson says Verey could have been an anonymous country lady - with a handsome house, a nice family who was devoted to her church and hunted, too. But this gardening chapter came late in her life and it became her career.

Her house, Barnsley House, and garden were relatively human scale - she created a garden with different parts and different features. And Robinson says that's what she likes about Rosemary Verey - that she made people think they could do it too.

Video of Rosemary Verey speaking about her garden in the winter:

____Book Excerpt: 'Love Affair with America'

By: Barbara Paul Robinson____

Chapter 10

Love Affair with America

1990s

Here in America you all want to know, you listen,

I love your enthusiasm.1

Rosemary’s love affair with America probably began on her first visit, but it was certainly solidified by the books she later wrote about American gardens. At the start of the 1990s, her book The American Man’s Garden came out, based on the same successful format as her earlier The American Woman’s Garden and the original The Englishwoman’s Garden and The Englishman’s Garden. This time, however, Rosemary was the sole author, although she acknowledges it was written in association with Katherine Lambert, her long-time personal assistant. The American garden writer Allen Lacy observes in the foreword that these two books about American gardens are “particularly useful in correcting the false notion that many Americans have about our horticulture’s being vastly inferior to that of Great Britain.”2

Americans in turn adored her for validating their own gardening vernacular. The books gave her a special link, since everyone included in the book, and many who helped with them, would be sure to welcome her whenever her travels took her anywhere near their vicinity. They were proud to have been selected as creators of special American gardens, and all were eager to fete her, generously hosting parties in her honor. These men and women formed a dedicated core of fans, but they were just a small fraction of her ever-expanding American network. In her own acknowledgements in The American Man’s Garden, Rosemary thanks a long list of people with whom she has stayed and others who have taken her around their gardens. It is a Who’s Who of Americans, not only of American gardeners.

Reflecting her extensive American travels, The American Man’s Garden includes essays from twenty-nine men with gardens in eighteen states, from the East to the West Coast and several states in between, including one in Vancouver, Canada. The essays written by the garden owners are grouped under the following categories: estate gardens; country gardens; plant collectors; city and town; poets and painters; and seaside, mountain, desert. In a lengthy introduction, Rosemary draws upon her interest in garden history and links American garden development to the early English settlers who carried plants and garden notions with them to the New World. And she generously gives credit to American plantsmen like the Bartrams of Philadelphia who sent native seeds and plants to England, changing the face of British gardens.

Bill Frederick recalls that she managed to make everyone in the book feel good. Since his own garden was pictured on the frontispiece of The American Man’s Garden, he certainly had reason to be grateful, but he appreciated how delicate her role had been with everyone involved. Bill understood that “People could easily take offense if one didn’t get the same amount of attention as the other one or didn’t get as many kudos or whatever. She achieved that by really being good at picking out the positive aspects of each person and each garden that she went to, so each one became different.” Her inscription to Bill on his personal copy of the book says, “For Bill and Nancy – the best garden is on page 142. I discovered once and for all that every visit is more and more magical.”

A knowledgeable and professional plantsman himself, Bill thought Rosemary had a rare ability to take in what she saw and “was one of the people that understood the kind of design that I was doing, and other Americans, better than any British person that’s ever been around here.” Not surprisingly, given her early university studies in social history, she “could adapt immediately to whatever the local conditions were and, to some extent, to the sociological aspects, the history of the area that the garden was in, especially if the garden was reflecting that.” She paid attention to what worked in each locality.

Following one of her fundamental rules, she always had paper and pencil in hand, noting the plants along with her observations. Unlike most other British gardening experts who came to America with “their usual palette of plants,”3 she did her homework and worked hard to learn which plants would work in the climate and conditions of the place where she was visiting. And if she promised to send seeds, as she often did, she always delivered.

Rosemary’s timing could not have been better. In the 1980s and 1990s, Americans were developing an increasing sophistication and interest in all things international, although most were initially modest about their own abilities. Americans looked to England to set the standards for great garden style. While there were those who emulated Japanese and Chinese gardens, and others who loved the formal structures of Italian gardens, Rosemary appealed to the vast majority of American gardeners who looked first and foremost to England for their models, but she encouraged them to think Americans were fully capable of creating their own garden aesthetic. “She was just there at the right time. You know when people were ready for all these lovely books. And she had the garden to show and of course her garden was also on the tourist circuit. It was plum there in the Cotswolds where all the Americans and other tourists passed

through. So she was perfectly placed geographically, as well as historically.”4

The fact that Rosemary Verey, the quintessential British lady, chose to feature American gardens as worthy of attention endeared her to a primed and receptive constituency. More importantly, her books showed Americans how much their countrymen and women already knew about creating memorable gardens, and she admired them. Tom Cooper, editor of Horticulture magazine, thought she was a “charming speaker. She made it a personal conversation in a very friendly way. She was very intimate. She admitted errors and it all felt very much like an honest account. You weren’t being lectured to, you were having a conversation with her.”

Rosemary’s American travel schedule each year built on the links she created through her books, especially her two books on American gardens. She usually went several times each year, covering great distances from coast to coast, with many stops in between. She became a regular in the Pacific Northwest, especially for the Northwest Flower and Garden Show, which began in 1989 and took place in Seattle in February of each year. Occasionally it was also held in nearby Vancouver, British Columbia. Next to Philadelphia’s, the

Northwest Show quickly became the nation’s largest flower show.

Dan Hinkley, plant explorer extraordinaire and founder of the renowned nursery, Heronswood, just outside Seattle, observed that “gardening really was at a fever pitch when Rosemary was at her height... especially in the Northwest here, which tends to be one of the centers of horticultural snobbery in the States. There was just an amazing devotion to the English mixed border. And trying to make it the American

border. All the people were going to England to buy plants and bring them back. And she was sort of the bridge between American and English horticulture for a long time.”5 She often spoke at the Northwest Flower Show and when she did, “she fortified our self-esteem, compared our gardening to that going on in Britain and often implied that we were doing it better in the Northwest.”6

Dan was impressed by Rosemary’s endless curiosity and her interest in local culture. Whenever she was in Seattle, she would “often go to the black Baptist Churches on Sunday. She loved the Pentecostals, the singing, the holy rollers.” He also enjoyed her sense of humor. Although she was not generally given to telling jokes, she could elicit laughs herself. One time Dan Hinkley picked her up outside of Seattle from

the ferry in his pickup truck. Since he had just been carting horse manure in it, he said, “Rosemary, I really apologize for not having brought the other car. I brought this pick-up, and it’s had horse manure in it. And she came back without batting an eyelash, ‘Oh shit!’ ”

Gregory Long remembers this as “a moment in time. Garden photographers certainly helped put her on the map and Rosemary’s books were everywhere. As America wasn’t producing many of its own gardening books, its gardening books came from England.” And her books sold extraordinarily well in the States, often exceeding 50,000 copies. For several books, Rosemary received from her London publisher, Frances Lincoln, a £40,000 advance, a staggering sum for the time.7

As Gregory Long recalls, “She loved being a celebrity.” He felt that in America “everyone here needed her, they needed her books. They had real content, they were not just lovely photographs; you could learn from them. They were written by a very intelligent voice that could talk to an American audience and they weren’t just about the gardens of the wealthy.” Barnsley was not a grand estate. So it was relevant

to ordinary people, and she perceived that relevance. As a result, Gregory felt her message was clearly that “You can make gardens like mine, borders like mine, containers like

mine; you can learn how to make a Laburnum Arch like mine.”

Ryan Gainey, an American garden designer based in Atlanta, “always thought she was much better known here

than she was in England.” In America, “she was contagious. Because you know how Americans are about the English. And how they just love to hear an English person speak, it just lifts them up. She just simply came on the scene when there was a great revolution in gardening in America. And somebody had to be the one and she became it. She was totally socially astute and gracious and very thoughtful toward everybody.

And people loved having her around. She integrated herself into the idea of American gardening through The

American Woman’s Garden and The American Man’s Garden. She had the personality that could take what she had learned on her own and teach Americans who were struggling.”

Ryan Gainey introduced her to his own client and Atlanta-based neighbor, Anne Cox Chambers, who owned Le Petit Fontanille, a lovely home in St. Rémy, Provence, France, with gardens covering over forty acres, almost twelve acres of which are formal ornamental gardens. Rosemary thought the outlines, which had been designed by her friend Peter Coats, were good, but that the garden needed some reviving.

Rosemary worked on various parts of the garden with Ryan Gainey. Serge Pauleau, the head gardener at Le Petit Fontanille for over twenty years, who oversees five full-time gardeners, recalled that Rosemary worked on an ornamental potager there and also decided to create a cutting garden: “Mrs. Verey designed that cutting garden and took the pattern from a book.” While she did produce a rough sketch, she followed her preference for laying the shapes and plants out on the ground. It has her usual geometric patterns, filled with flowers useful for indoor arrangements. Perhaps her biggest contribution to Anne Cox Chambers was to suggest she hire Tim Rees. Tim became a major force in the ongoing development of the gardens, adding strong outdoor rooms and rich tapestries of plantings.

When Anne Cox Chambers later invited Rosemary to a dinner party in Atlanta, she commissioned an extraordinary centerpiece for the table. It was a replica of the Barnsley potager, measuring eight feet long and three feet wide. Mrs. Chambers flew the florist who created this centerpiece in from New York – the plants were all live!8

Rosemary loved this sort of American extravagance; she was treated like a star or better still, royalty, wherever she went. While she enjoyed enthusiastic gardeners of any and all stripes, she was clearly happiest when in the company of the rich and famous, such as Oscar de la Renta. He was beginning to establish his own impressive garden in the northwestern corner of Connecticut with some structural

advice from Russell Page. Rosemary was asked to write an article about Oscar’s garden for House & Garden magazine and made a date to go see it. Although Oscar planned to meet her in his garden, a storm prevented him arriving in time. Despite his own position, Oscar admitted to her afterwards, “I was so unbelievably relieved . . . because I was absolutely terrified!”9 She in turn replied that she had woken

up worrying about what to wear to meet the great designer, saying, “Shall I wear my pink skirt and my white blouse?” They did finally meet in New York, and Oscar succumbed to her charms. She told him she had written in her diary, “Today I met a man and I think we are going to become very good friends.”

Oscar joined her long list of American admirers and soon he was giving her some of his expensive designer clothes as gifts. After she thanked him for some of the clothes he had given her, he replied, “I hope you’ll be a big hit in them. You are the new Oscar de la Renta glamour girl!”10 Oscar enjoyed “her feminine quality. Even in her old age, she could be flirtatious.” He responded to her warmth and astutely observed that “if she liked someone, and I don’t think she liked everybody, but if she liked someone, you really felt it. She had a magnetic force. She was a force of nature. Something strong, but not manly. Something very coquettish about her. She had tenacity, and an intensity and a passion.” Rosemary never

designed a garden for Oscar, but she offered advice and was quite forceful in her views, advising him to take out a line of roses he had planted under an allée of trees to open the view.

With so much travel and design work, some of Rosemary’s close friends and observers thought she was coasting a bit in her writing, capitalizing on her brand but without living up to her usual high standards. Indeed, two of her books, The Garden Gate in 1991 and A Gardener’s Book of Days in 1992, appear to be purely commercial affairs. The first was a small book in a series; it required her to write nothing more than a short introduction with short captions to pages of photographs of garden gates shown in various styles and settings. The second book was nothing more than a glorified calendar, with a short essay about each month and then empty pages for entries of dates and notes.

A Countrywoman’s Notes also came out in 1991 and though it is a charming book, it also required little work on Rosemary’s part. There was nothing original in it. The book was produced by Rosemary’s daughter Davina Wynne-Jones and was a compilation of some of her best of Country Life, selected from her columns written between 1979 and 1987 when Rosemary ceased writing for the magazine.11 The extracts are grouped by the months of a year and adorned with handsome engravings produced by a dozen artists. The topics are more about nature and life in the country over the course of the year than horticulture and cover a broad range from whippets, to bee swarms, to local Gloucestershire history.

As a remarkable tribute to their friendship, Prince Charles stated in the foreword that “Mrs. Verey . . . makes gardening seem the easiest and most natural thing in the world.” He goes on to say, “The garden at Barnsley House (which I love and you must visit) comes to life.” And then he puts Rosemary very much in the context of the Arts and Crafts movement, saying that “Mrs. Verey reveres the world of Ernest Gimson and Sidney Barnsley, those dedicated Arts and Crafts practitioners from nearby Sapperton. They would have approved so much of these wonderful wood engravings whose depth is such a good medium for revealing the intricacies of hedgerows. And wouldn’t William Morris have approved from across the willowy meadows in Kelmscott?” After a beautiful house, the next thing to be longed for, he said, was a “Beautiful Book. Here is one.” And then he signs “Charles.”12 A valuable endorsement not only of the book but of Rosemary and her gardens at Barnsley.

In the spring of 1994, Rosemary joined Christopher Lloyd for a lecture tour across America. Although they knew each other, Rosemary had not been Christopher Lloyd’s first choice. He had intended to travel with Beth Chatto, his close friend and a superb plantswoman, with her own specialty nursery and gardens in Essex. Christopher Lloyd, or “Christo,” as he was called by his friends, and Beth Chatto shared a passion for plants and swapped ideas and advice, some of which resulted in a book of their letters to each other.13 Unfortunately, Beth Chatto’s husband became seriously ill and she felt she couldn’t leave him, so Rosemary stepped into the breach.

At first Rosemary and Christo must have seemed an unlikely couple, but they proved to be a terrific team. They were “very supportive and cordial, but with quite a bit of goodhumored barbing. They were caricatures in a way. Rosemary was this stylish Liberty of London with a high-pitched, elegant voice and Christopher was this gruff, marbles-in-hismouth creature.”14 The two of them played off each other’s foibles, with Christopher making fun of her polite pastel palette and Rosemary joking about his messy ways. At one

lecture, she spoke first and showed a diagram of the color wheel as a point of reference. Christo purported not to understand it. When his turn came to show slides of his garden’s radical color combinations of magenta and orange, he teased, “You can see that I’ve never followed the color wheel.”15

Their banter amused their audiences and their shared seriousness about plants and gardens drew them into a strong friendship. They were certainly equals.

During their tour, Rosemary and Christo had dinner at Tom Cooper’s home in Boston. After a long, tiring day that would have exhausted anyone, Rosemary was still fresh and completely at ease, “just gay and happy and friendly.”16 She plunked Tom’s young daughter up on the kitchen counter and chatted away with her in the most natural manner. Somewhat flustered by his famous guests, Tom completely forgot to start cooking the wild rice in time, scrambling to find a quick substitute. As part of the conversation at dinner,

Rosemary praised Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher for restoring “the upper classes which were in decline,” and for “giving the aristocracy back a sense of itself, for giving the Royals back a sense of themselves.”17 Although not terribly political, she tended to be conservative and a strong supporter

of the royal family. Katherine Lambert, Rosemary’s assistant who was traveling with her and had more liberal views, jumped in to disagree, pointing out the unemployment problems and other inequities. After Katherine had gone on for awhile, Rosemary looked round the table, then back to Katherine and “very sweetly but very steely said, ‘Katherine. If you continue in this manner when we get back to the hotel, I shall have to strike you!’ ” Al though she purported to be joking, Tom was sure she meant it.

The evening ended after far too much scotch, and as Rosemary and Christo left, stumbling off in the direction of a waiting taxi, Rosemary stopped, looked back, and swirled her arms at two far-too-large hemlocks towering over the front porch and shouted back to Tom, “You must do topiaries! Topiaries!”

A day later, Tom drove Rosemary and Christo to stay with Joe Eck and Wayne Winterrowd, at their plant-intensive garden, North Hill, in Vermont. On the way, she talked very openly about her need to earn a lot of money for herself and her family, along with her concerns about the future of Barnsley and its gardens. Christo snored away in the back. Tom felt she was not just seeking his sympathy, but was clearly wrestling with these issues.

They arrived at the height of black fly season and Joe and Wayne warned Rosemary to cover herself with bug repellant before going out with them to see the garden. In the process of having herself sprayed, she was outrageously flirtatious with all the attentive men, later observing, “I could never have done this when David was around.” That observation was quite revealing. In America, Rosemary clearly enjoyed being free from many of the constraints she felt at home. “She allowed herself a measure of play and certainly

of freedom that she could never have allowed herself at home.” Her good friend, Andrew Lawson, observed that although she wasn’t herself aristocracy, she “was very grand and she got on well with the grand . . . in style she associated herself with the aristocracy. The Americans are completely unaware of all these things where the English are always very aware. As soon as she was in the American context she was free, free of all those things. And [the Americans] all made such a fuss about her and she loved it.”

She was also endlessly curious about things American and always fearless. On a visit to Harlem in New York City, she went happily into a leather shop that sold jackets. Her American companion suggested she shouldn’t go in because it was a “black” store, to which she blithely replied, “What does it matter?” She entered and bought herself a motorcycle biker’s jacket with multi-colored patches of leather and a cap to go with it. Afterwards, she boldly sported this outfit at home in Cirencester, despite her age.18 She also proved to be an enthusiastic Texas two-stepper, delighting in dancing late into the night with her American friend, Victor Nelson. And because she was not constrained by American conventions, she could be very direct. At one dinner party, she turned to her host and asked him point blank, “Now tell me, are you a millionaire or a billionaire?” His somewhat surprised reply was “Actually, I’m a billionaire.”

One of Rosemary’s proudest American moments occurred on August 13, 1994. Never having completed her university degree, Rosemary received an honorary doctorate in humane letters from the University of South Carolina at their summer commencement. In the photograph of the event, she looks happy and dignified in her academic robe and soft cap with a gold tassel. She thought this was “an important moment in my life,” and was delighted that the other honoree was a colleague “of Martin Luther King.”19More than just a Martin Luther King colleague, the other honoree was Andrew Young, who was Mayor of Atlanta, a Congressman, and the first African American to serve as American ambassador to the United Nations, among many other achievements.

Americans bought her books in huge numbers and also sought her advice. Sometimes it was an informal consultation, but there were serious assignments as well. If she so much as offered a suggestion, the garden owner forever after would boast of having a “Rosemary Verey” garden.

One of her serious assignments was for Richard and Sheila Sanford, who asked her to help them design ambitious gardens around the stone Cotswold-style manor house they were building in the Brandywine Valley just outside Wilmington, Delaware. The style of the house was very similar to Rosemary’s own Barnsley, with stone lintels, leaded windows, and architectural details imported from England, but concealing the most modern fiber-optic technology in its walls. The house site was atop a hill overlooking the magnificent rolling countryside. The Sanfords’ gardener, John Gallagher, suggested they call in an American, Neil Diboll, a wildflower expert, to help develop the meadows along winding drives throughout the extensive property. Because of Richard Sanford’s interest in coaching, these drives were intended for horse-drawn carriage events. When Neil Diboll came, he suggested the Sanfords hire Rosemary Verey for the gardens.

In response to a letter from Neil Diboll, Rosemary came to meet the Sanfords while in Wilmington giving a lecture and staying with her good friend, Bill Frederick, who lived nearby. Although the Sanfords had been intimidated by her fame and were reluctant to ask for her attentions, they were quickly enchanted with her warm, down-to-earth manner. Rosemary enlisted Bill Frederick to help do the actual planting. In addition to her work on their garden, Rosemary also introduced the Sanfords to English suppliers who could provide

Cotswold stone and other genuine English materials. While Bill Frederick and John Gallagher worked on developing the big picture, including long allées of trees to frame the striking views from the house to the distant landscape, Rosemary focused on the more formal plantings close to the house. Bill worked on the “overall concepts. Rosemary worked from the details up and [Bill] worked from concepts down.”20

Two of the gardens she designed for the Sanfords were patterned on her own garden, one a knot garden, the other a large, walled potager. The potager still exists almost exactly as she designed it, dominated by a large, handsome stone building at one end. Richard Sanford remembers her insisting on a full-scale mockup created so the size and proportions of this building could be designed precisely for the setting. Given the imposing scale of the main house overlooking this potager below, it was a wise move. By trying out

variations with a full-sized model, Rosemary ensured the garden folly would be proportioned exactly, large enough to be handsome but not so large as to overwhelm the potager or block the spectacular views beyond. Sheila Sanford has since become an accomplished gardener herself and keeps this potager true to her intentions; it remains one of the few gardens Rosemary designed that is still intact and complete.

The Sanfords also recall Rosemary’s common sense and willingness to listen to them, along with her savvy and practical country solutions. The woodland nearest the Sanfords’ house was overrun with multiflora rose and other invasive plants that had engulfed the handsome trees. No one had a good solution as to how to destroy these weeds without injuring the trees. State environmental laws prohibited the use of strong herbicides; bulldozing would be overkill. The weeds remained an eyesore, as well as a danger to the survival of the trees. One day, Richard Sanford said in passing to Rosemary, “How the heck do we get rid of that stuff?” Countrywoman that she was, Rosemary replied, “Have you thought about goats?” Astonished, Richard admitted goats had never occurred to him. He wasn’t quite sure what she was getting at but goats proved the perfect solution. A herd of goats was purchased and set loose under the trees within the confines of a temporary fence. “It was like a carpet cleaner – Whoosh – they ate everything! They were just like weed eating machines!”21 As the goats ate an area clean, the fence and goats were then moved on to the next overrun section and in short order, the beautiful stand of two hundred mature coffee trees was visible and the weeds were gone.

In the summer of 1997, the New York Botanical Garden commissioned her to design a potager along the lines of the famous one she had created at Barnsley. This was the only public garden she was ever asked to design and it was in America. Although this potager has not yet been built, the plans have been fully developed and the site chosen. From the start, Gregory Long made it clear that Rosemary’s garden would not be installed until NYBG raised sufficient funds to build it as well as endow its ongoing maintenance. Ever a realist, Rosemary knew that Beatrix Farrand had designed a renowned rose garden for NYBG in 1916 that wasn’t completed until 1988. She was confident that someday her potager would be installed, providing her a legacy in the United States. Perhaps that is why Rosemary ultimately chose to bequeath all her garden plans to the NYBG Library rather than an English institution.

When Gregory Long asked Rosemary to design this garden, he was puzzled as to why she had never been asked to design a public garden in England. “We could never figure it out. She was never asked to design a public garden there and she was never on the Council [of the RHS].” Having become a close personal friend of Rosemary’s over the years, Gregory and his partner, Scott Newman, often had Rosemary stay with them at their country house in upstate New York. In turn, they also often visited Barnsley but chose not to stay there. “She was sometimes too difficult, even cross, and as we were quite intimate, she often told us more than we wanted to know about her family relationships.” But when Rosemary came to stay with them in New York, she seemed to shed all that. “She really could drop so much of her baggage and jump into the moment. And when she came to us she was quite relaxed, not needing to be in charge.”

Rosemary’s potager for NYBG had to be on a much larger scale than her intimate one at home. It had to comply with all the applicable building codes, provide accessibility, and adapt to many other rules pertaining to a public facility. Rosemary worked with a large team of professionals, including architects, administrators, and other horticultural experts under the leadership of Dr. Kim Tripp, who at the time was

Vice President for Horticulture and later became Director, and was herself an expert in conifers.

Everyone agrees that the designs are completely Rosemary’s, but many other professionals participated, rather like the large team that had worked with her at Elton John’s. They helped produce the architectural drawings and computerized files. The work dragged on over many months, with Rosemary reviewing and revising the designs after they were drawn to her specifications by professional architects and draftsmen. Rosemary didn’t particularly enjoy the discipline of laying out all the lines with such precision, but she

would leave her sketches, suggested notes, and revisions, and they would all be incorporated in the next computerized version produced by John Kirk, the architect from the firm of Cooper Robertson working on the project.

As always, her real love was in the planting plans. She relished “deciding where the cold crops would go over years 1, 3 and 5 and the lettuces would go in years 3, 5 and 7 and then she’d switch them to allow for the rotation of crops and make a list for year 1 and year 2.”22 Characteristically open to the local culture, Rosemary was interested in the Bronx community that was primarily Hispanic and African American.

She learned about “Bronx Green-Up, and some of the vegetables that were grown by Latin American gardeners.

She met with them a few times and put a few of those in because she thought this is the Bronx and some things of local interest would be good in the vegetable garden.” Rosemary always paid attention to one of her basic rules, “Who is the audience and what is the message?” Here she made sure to include some ideas that would appeal to the neighbors.

Preferring to be hands on, Rosemary had the most fun working on this project when she was out in the garden. “She was dying to get out with the two gardeners on the ground with some open beds, lay out the hose and design the bed with the hose and start talking about which plants should go where.” Kim Tripp thought she had a kind of “gardener radar”; she could spot the working gardeners in any group. Then she would be completely engaged with them, soaking up and listening to what they had to say while offering

knowledge in return.

Although Rosemary liked best to be out on the site, she was thoroughly professional. “She came to the design work with enormous patience and intense concentration on every detail.” To Kim Tripp, she was the antithesis of the “twenty-first-century instant cad designer.” Instead, she would “very painstakingly and attentively draw out and think about all these details so it all came together very beautifully.” Kim

Tripp found her an inspiration. She was the real thing. She could talk about the most minute aspects of the plants in great depth and detail. She knew every plant “like one of her children so that she knew when it had been nice and when it had been naughty.”

Rosemary’s attention to detail and her reworking of the plans with almost excruciating precision were impressive. Rosemary was “thoroughly committed to taking however much time it took to get to the right answer in the design. [For example] she would spend days thinking about and detailing paving patterns.” Kim, a master multi-tasker, used to jumping quickly from one issue to the next, remembers being taken to task. “She would kind of look at me out of the corner of her eye with the twinkle when she could see that I was getting a little impatient about how long it was taking to figure out which corner this medallion should go in the paving and where exactly the step-over apples should end in relation to the radishes and then she’d look at me with that kind of expression, and I would realize that this really does matter, I should just not be worried about rushing off to do the next thing. She didn’t have to say a word. She would just look at me with this certain kind of sparky look and I would know, okay, so I should stop jiggling my knee.”

Rosemary could also grow testy. “Periodically she would get impatient with us.” Simon Verity, whom Rosemary brought in to sculpt a piece for the potager, recalls moments when she was “being such a bitch. She just crucified poor Kim Tripp who was doing her utmost to be helpful. ‘What are you doing? Why do you get involved at all?’ ” But Simon believes that her ill health was causing her to lose control. Even though she tried to carry on as usual, she was prone to lashing out in frustration when she wasn’t up to it.

Indeed her health was beginning to fail toward the end of the decade. Rosemary thought she had fought off the threat of arthritis some years before when she consulted a nutritionist who recommended she avoid dairy products and wheat. But with age her energies began to flag and she was afflicted with polymyalgia rheumatism; as a result, she was often medicated for the pain.

But America continued to honor her. In October 1998, she went to Boston to receive the George Robert White Medal of Honor from the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. Her friend, Jerry Harpur, whom she enlisted to accompany her, recalls that at one point during her acceptance speech, she chose to tell her Boston audience that when David Verey had asked her to marry him, she had replied, “Yes, but I won’t pick up your socks.” When Jerry asked Rosemary later where that story came from, it was clear she had simply made it up on the spot. Still, it brought the house down. The award recognized her “as an internationally renowned plantswoman, garden designer, and writer. Mrs. Verey’s garden at Barnsley House, one of England’s finest and most famous, delights thousands of visitors in practice and through the written word. Mrs. Verey’s lifetime of gardening has offered boundless inspiration.” The medal itself was for her “overwhelming personal and professional commitment to advancing the world-wide interest in horticulture through her writings and lectures and especially by sharing her magnificent garden at Barnsley House.” The English horticultural establishment would not finally award her their highest honor until the following year.

Excerpted from the book ROSEMARY VEREY by Barbara Paul Robinson Copyright © 2012 by Barbara Paul Robinson. Reprinted with permission of David R Godine.

Guest:

- Barbara Paul Robinson, author of "Rosemary Verey: The Life and Lessons of a Legendary Gardener."

This segment aired on December 21, 2012.