Advertisement

A Son Faces His Father's WWII Ghosts

Resume

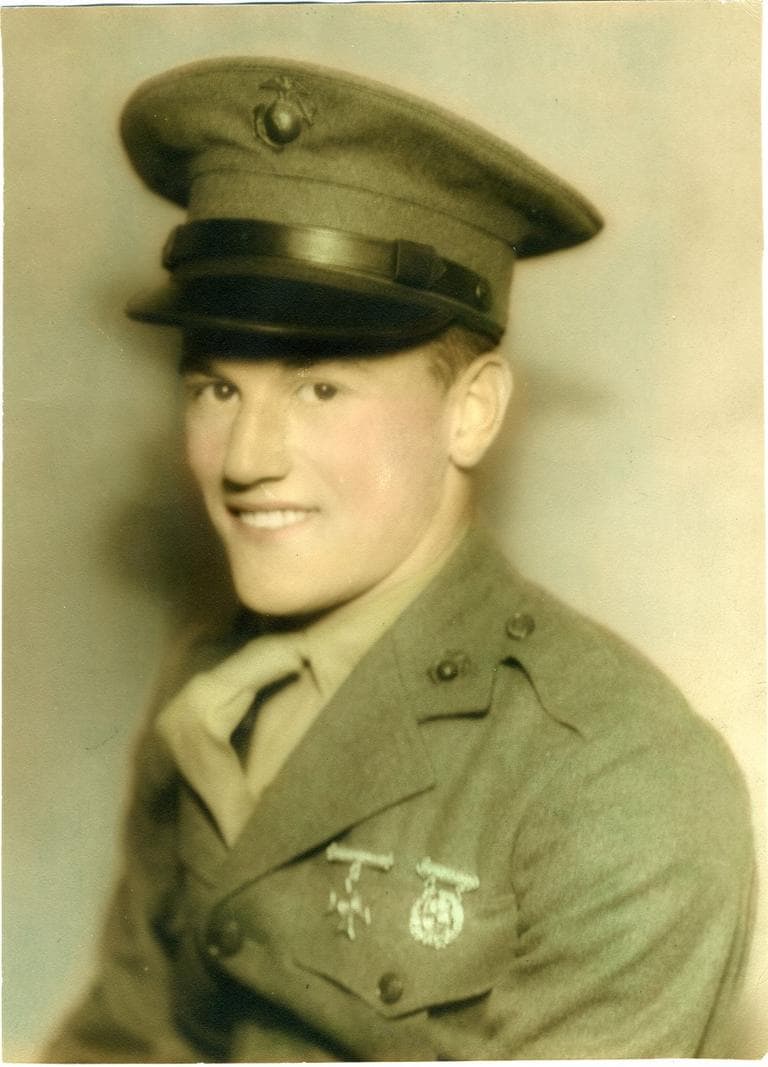

Steve Maharidge served as a Marine in the Pacific. When he came home, he was subject to fits of rage.

His son, Dale Maharidge, believed the war was the source of that rage, based on a photo his father kept. It showed Steve and another Marine.

When his father died, Dale tracked down members of his father's unit to find out who the other man was and why his father couldn't forget him.

"I learned that my father had two major blast concussion injuries," Dale told Here & Now's Meghna Chakrabarti. "My father's behavior — his screaming, his craziness — is one symptom of traumatic brain injury. I started meeting these guys. I started meeting their kids and I learned that our house was not abnormal, that there were many, many troubled families out there. World War II never ended for a lot of these guys, and their families by extension."

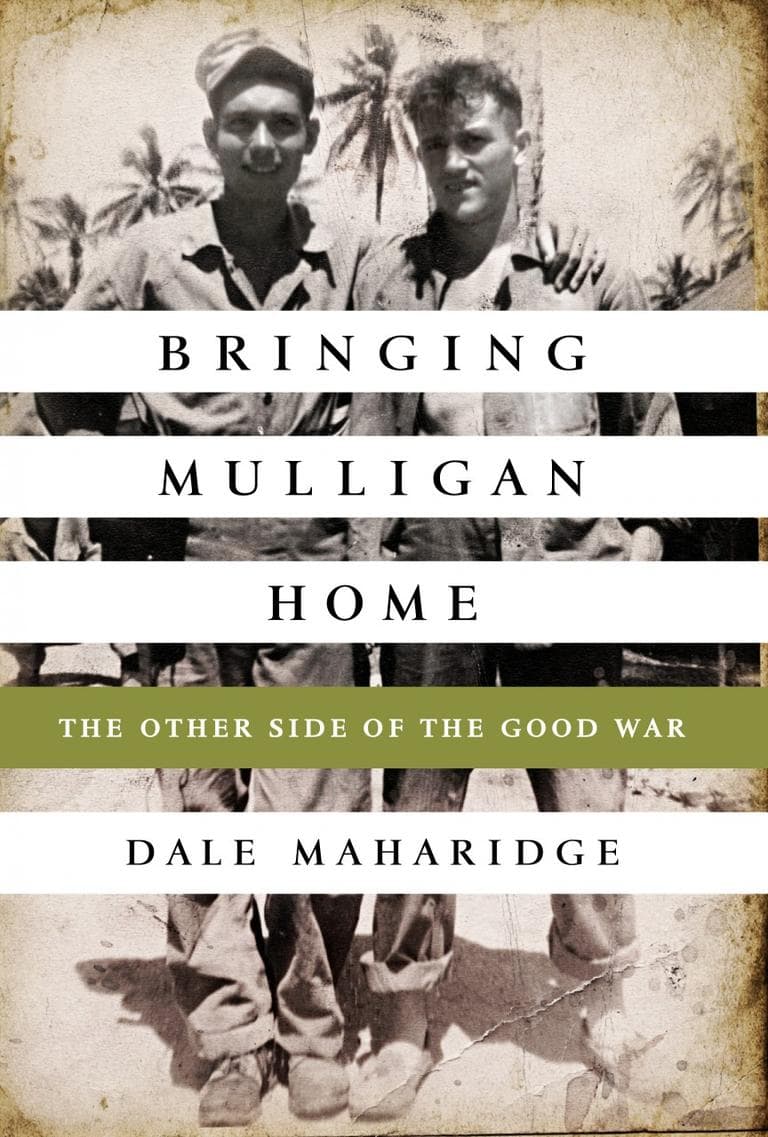

Dale, who is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist, writes about what he learned in a new book, "Bringing Mulligan Home: The Other Side Of The Good War."

____Book Excerpt: 'Bringing Mulligan Home'

By Dale Maharidge____

Introduction

Something was wrong in our house. My father had a depth of rage. The majority of the time he was a great dad. Then something would snap, and he temporarily became the worst. He was consumed by an anger that seemed at the edge of violence, but he always pulled back, except for one day in 1960, when he struck my mother. There was blood on the black and white wool wall-to-wall carpet at the base of the stairs. The domestic battle continued behind the closed bathroom door as our mother bandaged herself to stop the bleeding of her temple. The image of that ugly splotch coagulating on the carpet remained in my nightmares for years. Decades later Mom told me that she issued an ultimatum—she’d walk if that ever again happened.

Dad never again hit her. Yet the rage remained. It was never really targeted at us. It seemed to be focused on some unseen entity.

When I study my baby pictures, taken by my father with an Argus C3 camera, I smile in every frame. As a toddler, I grin ear to ear bundled up and wearing a wool cap while playing next to my sister in our side yard on an Ohio winter day. I was clearly a happy kid. In later pictures—age eight, nine, ten—however, I’m frowning, intense. My father’s rage had become my own.

Dad seldom talked about the war. I learned pieces about it beginning when I neared puberty. Dad disclosed things when he and I were alone, usually in his basement shop, where he had a side business grinding industrial cutting tools. I knew instinctively never to ask questions. I just listened. I never broke this unspoken rule.

The war was always present in the form of a picture of my father and another man that Dad had set, at adult-eye level, atop the gas meter next to the machine where he most often worked. It clearly meant a lot to him. Dad once mentioned that it was taken on Guadalcanal. Except for one other time, he said nothing else about it. I became obsessed with the image. The picture came to represent everything that I didn’t know about my father and the war, his rage that sometimes caused him to scream, and it was a great gnawing mystery as I grew up.

When my father died in 2000, the picture remained an enigma. That’s when I began a quest to locate men who were with Dad in L Company, “Love Company” in the military jargon of the era. Love Company, part of the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, Sixth Marine Division, fought in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

Over the course of twelve years I spent ceaseless hours making hundreds of phone calls; I sent out hundreds of letters. Many men had common names—you can’t begin to comprehend how many Robert Harrisons and A. Robertsons that I telephoned, all false leads. And there were those with complex names who appeared to have simply vanished. (A startling number died between 1946 and 1950, and though the database that I used to find their records didn’t give causes of death, I’d learn that many drank themselves into early graves.) I got hold of sobbing widows, children who were more troubled than I was by their late fathers’ war experience.

A majority of the men were dead by the time I finished—over twothirds by a rough count, though I’ll never know for certain.

I conversed with twenty-nine guys from Love Company and got to know half of them really well. What’s remarkable is that most of these men, nearing the end, were talking. Many had spent their lives like my father, shunning any discussion of the war. These were in some cases essentially deathbed confessions. I discovered a World War II story that had been impossible to get for over a half a century. The silent generation was finally speaking in its octogenarian years.

I initially focused my quest on learning about the man in the picture with my father. That man represented something that happened to Dad, and I needed to know what it was.

I found six guys who were present when the man died. One Love Company veteran told me I was the first person in sixty-five years whom he’d talked to about the incident—he’d carried Herman Walter Mulligan’s body that day. Despite this, Mulligan’s body was, oddly, listed as not recovered. I fixated on finding his remains. For US Marines, there is semper fidelis, commonly shortened to “semper fi.” It means always faithful or loyal—never leave a buddy behind. But I can’t say that I was personally motivated by semper fi. I was never a soldier. I never heard my father utter those words. Yet he lived them by keeping Mulligan’s memory alive his entire life. So in essence, for my father, I was abiding by semper fi as I sought to bring Mulligan “home,” by at least putting a name on his grave. That would, I felt, put some of Dad’s demons to rest.

My search, however, broadened as I came to know the men of Love Company. Mulligan was like a ghost I grew up with; to this day, after a dozen years of research, he remains something of a ghost. This book does not end with a surprise discovery of Mulligan’s remains nor is it about his life and times. The picture that I was obsessed with as a boy turned out to be the vehicle that propelled me on a journey to learning something much larger and equally fitting to honor the memory of Mulligan: an understanding of that war. In addition, through this quest I finally came to truly know my father.

The years spent researching this book were at times traumatic. For a period in the middle, when my mother fell ill with cancer, I gave up. Frankly, a lot of it is a horrific story. I would have slept better many nights had I left it alone.

But I was pulled back. I needed to write this book because World War II followed a lot of men back to the United States. Ignored in many “good war” narratives is what really happened overseas—and most important, what occurred after the men came home. Many families lived with the returnee’s demons and physical afflictions. A lot of us grew up dealing with collateral damage from that war—our fathers.

This is not a “trash your father” memoir, if it is a memoir. (I loved my father. At his core he was a good man. I also love the guys from Love Company, except for one—why will become clear later.) This is a reported book, told from a personal perspective, about the outfall of war. After unearthing what my father went through, I’m amazed that he wasn’t more damaged. He grew less crazy tempered as he aged, and near the end I saw perhaps the man that might have existed before he set off for the Pacific.

As I was writing this book, a new generation of US soldiers was returning home after brutal tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, many with the trauma of wounds both physical and mental. Some of those soldiers, especially those wounded by roadside bombs and suffering blast concussion, will have the same issues that my father struggled with. Their children will wonder why their mothers or fathers have rage or are depressed; those kids will face the puzzlement that I had as a boy. Joe Lanciotti and the other guys from Love Company know the answer. But they will be long gone. After my multiyear mission to learn from them, my goal is to put the past in touch with the future.

I hope this book helps those kids learn about their parents and war and also bring home to them an understanding of what happens once the bullets and bombs stop flying—wars never end for the participants and their families.

Excerpted from the book BRINGING MULLIGAN HOME by Dale Maharidge. Copyright © 2013 by Dale Maharidge. Reprinted with permission of PublicAffairs.

Guest:

- Dale Maharidge, author of "Bringing Mulligan Home: The Other Side Of The Good War." He tweets @DaleMaharidge.

This segment aired on June 13, 2013.