Advertisement

Steve Almond's Manifesto Against Football, Continued

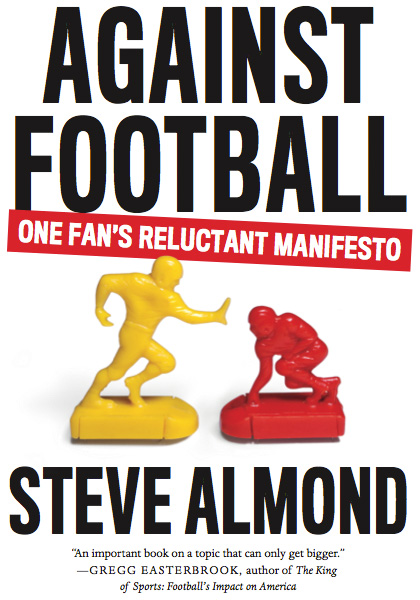

Steve Almond has been a football fan all his life - especially of the Oakland Raiders. No more. He wrote a book that was published last year in which he outlined his reasons for never watching the game again.

In "Against Football: One Fan's Reluctant Manifesto," Almond cites a number of reasons, including the increasing body of research that playing the game causes brain injury. But he also wonders whether our addiction to the sport leads to a tolerance for violence, greed, racism and homophobia.

Almond has written a new afterward to the book and joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about his stance against 2015 football.

Interview Highlights: Steve Almond

On how Almond gave up watching football

“I feel like I should have one of those - a year’s sober kind of a thing. I didn’t watch and it was terrible, because I love football and I get why people love it so much and I was a member of the church in good standing for four decades. The game was a place of refuge, for fans in general, but especially for guy fans. It is a place where the complications and frustrations and moral duty of adult life just disappears - poof - and you are re-immersed in those pleasures of childhood and the kind of magical thinking that prevails in childhood.”

On the NFL’s response to concussion lawsuits

“For me, the most fascinating moment of everything that happened in the offseason was the announcement by the NFL itself in federal court. Their actuaries, in response to this massive lawsuit filed by all these former players saying, ‘you lied and covered up the damage done to our brains playing this game’, estimated that 30 percent of players were going to end up with long-term cognitive ailments, which is a polite way of saying brain damage. There is no business in America where, in the workplace, up to a third of the employees are going to get brain damage. That’s not a tenable model morally for the American people, and it’s not a tenable model business-wise. I really, honestly thought, 'that’s it.' They spent all these years trying to keep people from realizing the profound dangers of the game and now they themselves admit what other industry in the United States wouldn’t find even close to acceptable.”

One of the central rationalizations people use of football is that it’s a way out for certain kids. I don’t believe that football is the right model for empowering communities who are disadvantaged economically and socially and educationally.

On media coverage of the NFL

“What happened is, that huge story about a workplace in America in 2015 where a third of the employees get brain damage, got completely wiped out by these very gratifying seductive scandals about brutal actions that occurred off the field. In this way, I think the fan is made to feel consistently by the media like a victim rather than what we really are - the sponsors of the game. The Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson stories allowed fans to get very angry and indignant, and not see any relationship to what’s happening on the field. I think about it oftentimes from the point of view of the brain. You don’t know what the external context is, you just know if you’re knocked senseless you’re suddenly no longer functioning. The brain inside Ray Rice’s girlfriend, now wife, was knocked senseless, and we all saw that and got upset; it seemed monstrous. Brains are knocked senseless in that same manner every Sunday and it’s because in the context of football that we say, ‘great’. Football has managed to sanitize the violence.”

Advertisement

On drawing a line from football to stereotypes of young black men

“Look at the case of Michael Brown or Eric Garner, these were two African American men, in one case a teenager, who were described by and treated by law enforcement as if they had monstrous powers. In Ferguson, you have the officer talking about being shaken around like a rag doll, and lines that are suggesting that Michael Brown was this huge figure. Well he was 6-foot-5 and so was Darren Wilson, and yet there was this exaggerated sense of his menace. Eric Garner, who was a big guy, was tackled by four guys. And what’s so eerie about it and the connection I’m trying to draw here, is the guy who tackles him and applies the fatal chokehold, is he isn’t wearing police blues, he’s wearing a football jersey. In this country there’s a long tradition of grotesque stereotypes about African-American men and men of color, which exaggerates their physical menace in order to justify menace against them. That is the line I would draw in this rash of cases we saw. One of the central rationalizations people use of football is that it’s a way out for certain kids. I don’t believe that football is the right model for empowering communities who are disadvantaged economically and socially and educationally. I think this is a perversion of our values, which should say that every kid matters because of their intellect and morality, not because they get really good at playing a brutal, murder ballet game that we really love watching.”

Guest

- Steve Almond, author of “Against Football” and co-host of the WBUR podcast Dear Sugar Radio. He tweets @stevealmondjoy.

This segment aired on September 3, 2015.