Advertisement

Monsanto CEO Talks Crops, Pesticides And Farms

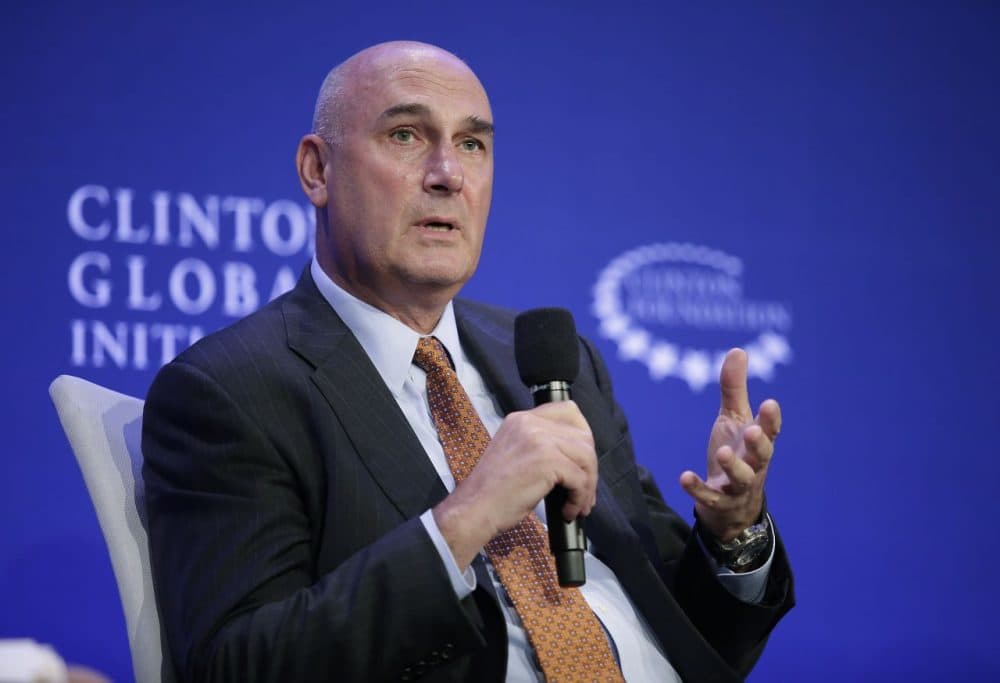

Monsanto is one of the most controversial companies in the world. Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson conducts a wide-ranging conversation with, Hugh Grant,CEO of the agrochemical and biotech giant, about pesticides, genetically modified crops (GMOs) and the future of agriculture. This is part one of a two part interview.

Interview Highlights: Hugh Grant

Why do you think Monsanto has become the ‘face of corporate evil’ in this country?

“I think a piece of this comes with – we’re the market leader, the original inventor of a lot of these technologies and I think sometimes when you’re first out the gate, when you’re in a leadership position like that, you become the de facto spear catcher. I think for us that was maybe the genesis of this, and I think there’s a piece of, also, this – we’re right in the middle of this discussion on food and agriculture and the safety and security of food, so I understand some of the concern. But I think, nevertheless, there’s work to be done in explaining more clearly where food comes from and how food is produced.”

What part of the concern do you understand?

“I think in the U.S. today there is still a very significant misunderstanding about science. When you think about the consumer today, there’s more work to be done in helping to explain the science behind these technologies, so I think a lot of the concern comes through that. My experience has been, when you can explain what these products do and you can explain the extraordinary benefits that they bring to growers and to society, you usually meet a middle ground. That’s been my experience over the years.”

On concerns about genetically engineered seeds

“So it’s springtime in St. Louis, in a few weeks’ time, the Midwest will start planting crops, and those crops feed the world. This is the 20th spring that the U.S. has planted GMOs; it’s the 20th anniversary this year for biotech around the world. So billions of acres, trillions of meals served and not a single health concern, so I think the weight of science and, frankly, the evidence of practices is pretty clear on this.”

So why are there still so many protests, in the U.S. and abroad, against genetically modified seeds?

“I actually think it’s improving. I think the dialogue – so here’s the interesting thing, and it’s more evident today than I think it was 10 years ago. It doesn’t matter where you go, if you’ve got a party on the weekend there’s usually a conversation about food and food is front and center in many discussions, and any time there’s a conversation about food, usually Monsanto is at the table, and I think it’s a healthy thing, but I think of if you look, you know, GMOs have been around 20 years. If you think of it the next 30 years, we’re gonna have to figure out how to grow twice as much food on a shrinking footprint. We’re gonna have to figure out how to grow more on a smaller footprint worldwide and use less stuff. We’re gonna have to make agriculture much more sustainable, and I don’t think GMOs are the silver bullet there. I think there’s other things that we’re gonna have to figure out, how we look after soil better, how we use less water, but I see that conversation improving. The quality of that dialogue is improving and I think that’s cause for optimism.”

Advertisement

You think by using genetically modified seeds, we can use less water when planting crops?

“This is the conundrum. There’s three things that as a civilization we’re going to have to do simultaneously. We’ll have to do, I think within the lifetime of our children or for some of us our grandchildren, and the three things that we’ll have to figure out to do simultaneously are number one: How do we use less water in agriculture, because agriculture is gargling its way through about 70 percent of the world’s fresh water, so obviously we need to improve that. Number two: How do you change the slope in the curve of food security? Because as many parts of the world don’t have enough to eat, and Africa this year is heading into another famine. We see the front end of that right now. And number three: How do we help solve climate change? I think that the key in this is how you do three things at once. You can’t say ‘I solved food security, but I’m really sorry about water,’ or ‘I’m using less water, but I apologize about climate change.’ I think agriculture can contribute to all three, and I thing GMOs and microbials and better use of data, I think the convergence at hand for these technologies has a really important part to play in solving these three pieces.”

Why is there a need for Monsanto to sue farmers that reuse their seeds instead of buying fresh ones every year?

“Yes, one of these urban myths.”

Is it an urban myth? You have sued farmers in Canada, and won.

“Here’s the reality. We sell to about, in the U.S., a quarter of a million to a third of a million farmers every year. We’ve been selling to that same group for 20 years. So 20 times a third of a million, you’re about 7 million customers that we have sold to over the last two decades, and we will have sued less than 10 growers in that time. So any business - a business where you sue your customers isn’t really great for business. If you’re in a generational business where you’re selling to farmers and hoping to sell to their sons and daughters, that doesn’t really shake out. The reality is, and that’s why I call it a myth, growers buy fresh seed every year because fresh seed yields better crops. They’ve been doing that with corn since the 1940s. In fact, when America fed a war-torn Europe in the 1945 to 1950 time frame, America flipped to hybrids. You buy fresh hybrids every single year, and now the world has followed them. France followed America in the 1950s, Vietnam made the move in the 1970s, so it’s a nice soundbite, but the reality of agriculture is, you’re never going to force farmers into doing something that doesn’t make business sense, and they plant fresh seed because it yields more.”

So if a farmer decided not to buy new seed and reuse their older ones, you would have a problem with that?

“I’d have a problem with it, but the practice is 96 or 97 percent of them are planting, and corn, 100 percent of them plant fresh corn every year. Nobody stores corn because the second year you plant it, the yields are lousy. That’s the nature of a hybrid, and in soybeans you get disease, bugs and broken seed. So 95 or 97 percent of them are planting fresh seeds. The challenge of this is, there’s a piece of our technology in there, just in the same way as if you buy a DVD or a piece of recorded music, so there’s an expectation that we get paid for the investment we make. That’s a fair deal, and farmers honor that.”

What would you say to the people that still, after this interview, dislike everything Monsanto does?

“I think, I mean it’s a complex one. I’d ask people to take a step back, to think about our little blue planet, and think about food production, not just this harvest but for the next 20 or 30 harvests and think from the perspective of how are we going to feed a population that has grown significantly. The irony of the population growth and the life of their kids or grandkids, the irony is that the growth is going to come in many parts of the world that are largely or more affected by climate change. So the world is going to be warmer, dustier, drier and thirstier, and we are going to have to grow more stuff against that backdrop. I guess I would ask your listeners to think about how we’re going to produce more food and how we’re going to feed the world, and a lot of that is going to be done in the U.S., Brazil, Argentina and I think Mexico, and that food will be moved and we’re going to have to figure out how we apply technologies to do that in a much more sustainable manner. That’s a long answer, but I think the faster that we can get to a central dialogue rather than an either-or, that would be a healthy outcome for everybody I think.”

See part two of this interview.

Guest

- Hugh Grant, CEO of the Monsanto Corporation.

This segment aired on March 30, 2016.