Advertisement

Suicide Prevention Act Remains Legacy Of A Senator's Son

The Garrett Lee Smith Act, a federally-funded suicide prevention program, is up for renewal. The renewal has been written into various versions of various bills. That's not uncommon. What is uncommon is the origin of the initial legislation - a father who lost his son to suicide 13 years ago.

Reporter Joanne Silberner takes a look at how this suicide prevention program got its start - and where it is today.

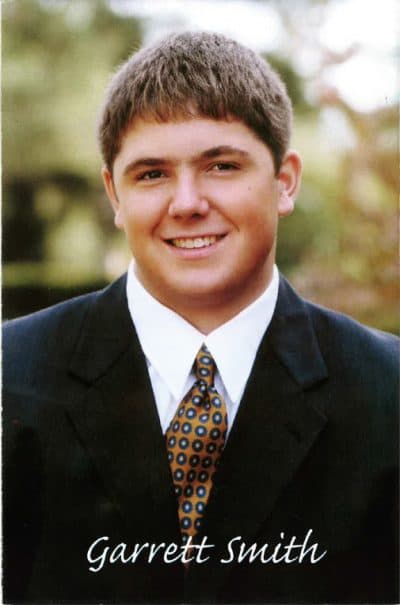

Suicide, it is said, is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. In 2003, Garrett Lee Smith took that permanent solution. Thirteen years later the effects are being felt in the continued grief of his parents – and the work they’ve done to prevent other families from suffering as they have.

Garrett Lee Smith was the son of Gordon Smith, a U.S. Senator from 1997 to 2009. Garrett, a college student, had struggled a bit with reading disabilities, and more seriously, just before his death, with several bouts of depression.

Still, neither his parents nor those around Garrett at college expected that after his bouts of trouble sleeping, alcohol abuse, complaints of low self-esteem and giving away possessions such as a TV and his CDs, he would take his own life. On the day before his 22nd birthday, he played with his beloved bulldog Ollie, enclosed the dog in the kitchen with extra food and water, wrote a suicide note, and took some pills and alcohol.

Ten months later, Gordon Smith introduced the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act on the Senate floor.

“Most of you can probably discern by now that my emotions are somewhat tender,” Smith began, his voice breaking. “I didn’t volunteer to become a champion of this issue, but it arose out of the personal experience of being a parent who lost a child to mental illness and suicide.”

He wiped his eyes and after a long pause, he continued, without looking at any notes.

Advertisement

He talked about Garrett, and about the importance of ending the epidemic of youth suicide. And he introduced bipartisan legislation that would support three years of suicide prevention and intervention programs in states, on college campuses and on Indian reservations.

After Smith’s emotional speech, Senator Harry Reid stood up and talked about his father’s suicide. Then it was Don Nickles of Oklahoma, also talking about his father. Multiple Senators from both sides of the aisle talked about others they’d known, and heartily supported Smith’s plan.

The Garrett Lee Smith Act passed, 100 to 0, and after some changes on the House side, it passed there too. It was signed into law Oct. 21, 2004, with $82 million in funding.

"I didn’t volunteer to become a champion of this issue, but it arose out of the personal experience of being a parent who lost a child to mental illness and suicide."

Sen. Gordon Smith, introducing the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act on the Senate floor

The act covered three years, and has been renewed each year for about $30 million. This year both Republicans and Democrats in Congress are trying to provide more of a guarantee with new legislation that promises funding for the next three years, plus provides an extra $12.5 million for a resource center and for college campuses.

So how has the Act been working so far?

Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, got a three-year Garrett Lee Smith grant that went into effect in 2014. Their programs include online and classroom education on suicide prevention for dorm RAs, interested students and staff. There are also suicide awareness walks, an annual fair, classroom lectures, available counselors, outside speakers, an art show, theatrical performances, and classes in resiliency aimed at men.

Psychologist Farrah Greene-Palmer, who administers the grant at WWU, says a major problem for teens and young adults is that they don’t recognize the symptoms of depression that can lead to suicide, and they don’t do anything about it.

“It’s like not knowing the symptoms for heart disease, you know, it’s like some people don’t realize this is a problem,” she says. “They’ll admit I’ve been sleeping all day, I haven’t been eating, I’m not interested in activities … They don’t think it’s that serious.”

Until it’s too late. So the educational activities at Western Washington University that come out of the Garrett Lee Smith Grant are aimed at alerting students, or people around students and making sure students know where to go to get help.

It looks like it’s working at Western – there were three suicides the year before the grant went into effect, and none since. But that’s too small a database to say for sure. On a national scale – the Act gets good grades. Richard McKeon is head of the suicide prevention branch at the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. He and several others have spent years evaluating the act, comparing counties where there was a Garrett Lee Smith Act program to counties that had no programs.

“The estimates were that during the period that the study covered, which is 2007 to 2010, there were about 427 fewer deaths by suicide because of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act.,” he says. And there were 79 thousand fewer attempts. But there’s a caveat, he warns. While the impact was measurable the year following the activities, it fades out after that.

McKeon and others have data that suggest that there’s a clear cost benefit — Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act activities have more than paid for themselves through reduction in emergency room and hospitalization costs for young people who attempt suicide.

But a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that death rates among 15 to 24 year olds are going up – for example, for young males the rate went from 16.8 per 100,000 in 1999 to 18.2 in 2014, and in females from 3.0 to 4.6.

McKeon says that’s not a failure of the Act – suicide attempts and deaths would have been even higher without it. He credits Gordon Smith’s floor speech back in 2003 for saving young lives.

As for Gordon Smith himself – he lost a re-election bid in 2008, and he’s now head of the National Academy of Broadcasters. He still gets letters from parents whose sons and daughters have been helped by the programs set up through the legislation. He thinks the program will be re-funded. “I believe this funding will continue, I believe it needs to continue, it is saving human lives,” he told me recently.

Several Republican congress members are vying to include the provision in several different bills, and while it is difficult to predict anything about the current Congress, many Capitol Hill watchers think that some form of the Act will be renewed. Meanwhile, Western Washington University has committed to funding its own suicide prevention activities after its grant runs out in September.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24/7 at 1-800-273-8255.

Reporter

Joanne Silberner, freelance reporter and artist-in-residence at the University of Washington. She tweets @jsilberner.

This segment aired on June 10, 2016.