Advertisement

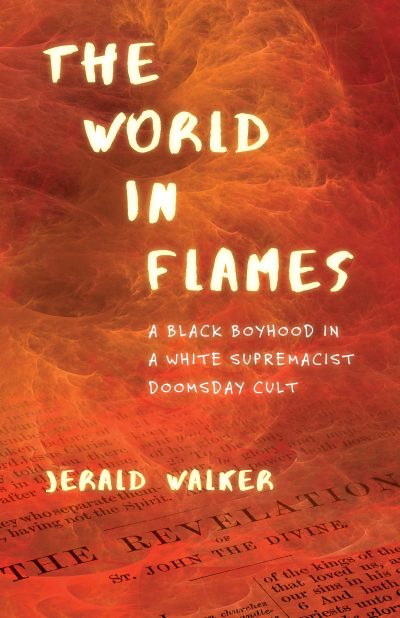

Memoir Documents Author's Youth In 'White Supremacist Doomsday Cult'

Jerald Walker's youth was anything but typical.

The African-American boy on the South Side of Chicago grew up with his blind parents and siblings as members of a "white supremacist doomsday cult." The Worldwide Church of God had them preparing for, and believing in, the imminent end of the world.

The Walker family tithed much of their income, lived in semi-poverty and accepted the belief that God condoned slavery and believed that whites should rule the world.

Walker joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about "The World in Flames," which describes both his difficult childhood and its unraveling, as church leader Herbert W. Armstrong was revealed to be a fraud, and his siblings gradually abandoned the religion.

Book Excerpt: 'The World In Flames'

By Jerald Walker

The lights are off, signaling that pagans are not welcome here. They come anyway. Every few minutes a mass of bodies marches across the lawn and climbs the stairs, fingers already reaching for the bell. We don’t answer. Usually the pagans leave. But sometimes the bell is pressed again, or the door bangs impatiently. Then our father rises from the couch, a print Bible in hand he can’t read, there only to emphasize his position and to help shield against evil. As soon as he steps onto the porch the visitors surge forward with their bags extended, and our ears fill with their sinful plea.

Our father explains that it’s against our religion to celebrate Halloween. A couple of the older kids always laugh, perhaps believing this is a continuation of the gag that had us bathe our house in darkness. The intention is to give the impression that no one is home, but the effect, for some, is to make the premises foreboding, potentially dangerous, and that draws them to us.

Advertisement

At first they’re not disappointed: a grave-looking, blind man clutching a Bible could prove to be the highlight of the evening. And this is even before he mentions the fiery pits of hell. When he does, the laughter starts up again. Our father counters it with scripture, something from the book of Colossians about idolatry and Satan. He usually gets no further than two verses in before the children interrupt him. “Trick or treat!” they demand, making it clear the gag has gone on long enough and it’s time to stop this crazy talk and deliver the Milk Duds and Snickers.

Each time my father goes outside, I creep close to the door so I can get a better view of their costumes. When he returns, I go back to my post by the picture window next to Bubba. We watch a few kids linger on the porch, still unconvinced that this isn’t a trick before they slouch downstairs toward equally perplexed parents, and then everyone moves toward another house, a straggler casting a final glance our way. We wait for the next group, and the scenario is repeated. In the morning our house will be covered with raw eggs, our garbage bins overturned. But at least the holiday will be over.

I hate Halloween. I hate all the pagan holidays, but Halloween is especially difficult to endure because I know in my heart it’s harmless fun. Does God really intend to sear the skin off my fifth-grade classmates for cutting witches from construction paper and taping them to the walls? Did he actually write Mrs. Montgomery’s name in the Book of Punishment for allowing her students to wear their costumes to school on the day before Halloween? Did he not see how unhappy I was watching my classmates prance around like actors on a stage, a dress rehearsal for the biggest night of the year? Or did he only see my sinfulness, how I longed to be that pirate with a puffy white shirt and plastic sword, or that cowboy in the suede vest and boots with twirling spurs, or that football player in shoulder pads and cleats, or that policeman, or that lumberjack, or maybe even that prostitute who tripped into the room in high heels and a skirt so short that we caught flashes of her underwear before she was sent to the principal’s office to wait for her mother to take her home.

Despite my prayers for the strength to not covet these costumes, I wanted them all, and if God would punish me for that sin, he would punish me for this one too: yesterday after school, I stood in my basement’s bathroom wearing a wig, pumps, and a dress. The dress was purple with small white flowers; the pumps were black with ribbons on the toes. I think the clothes were Mary’s, but they could’ve been Linda’s. I was certain the wig was my mother’s. She had several of various styles and colors, and the one I selected had long, brunette curls that fell beyond my shoulders, the same one my father had donned once before sitting at the dinner table, causing Tommy to laugh so hard that the orange juice he’d just swallowed sprayed from his nose. I wondered what my neighbor Paul’s response would be when I emerged from behind the door.

This was his idea. He said he and his little sister dressed up in their mother’s clothes and wigs for fun all the time. Since I couldn’t officially celebrate Halloween, he reasoned, this would be the next best thing. I agreed to give it a try.

Excerpted from THE WORLD IN FLAMES by Jerald Walker. Copyright © 2016 by Jerald Walker. Reprinted with permission of Beacon Press.

Guest

Jerald Walker, author of "The World in Flames: A Black Boyhood in a White Supremacist Doomsday Cult" and a professor of creative writing at Emerson College. He's also author of "Street Shadows."

This segment aired on October 6, 2016.