Advertisement

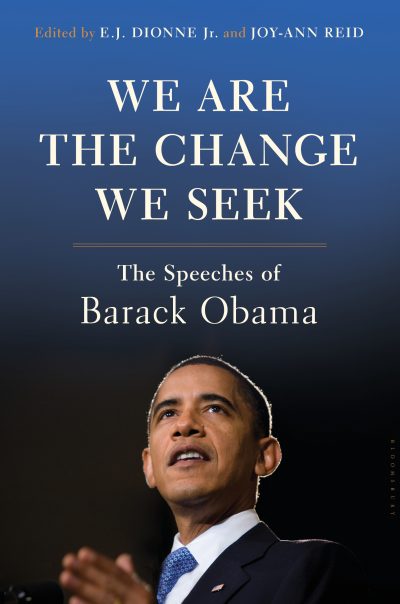

'We Are The Change We Seek' Looks Back At President Obama, In His Own Words

Resume

Barack Obama was a young U.S. Senate candidate when he burst onto the national stage with his keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in 2004.

In 2008, he made history as the first African-American to be elected president. Tuesday night in Chicago, he'll deliver his farewell address.

Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson talks about the book with E.J. Dionne (@ejdionne) and Joy Ann-Reid (@joyannreid), editors of "We Are The Change We Seek: The Speeches of Barack Obama."

Watch: Obama's Speeches From The Segment

Obama's speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention

Obama's Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 2009

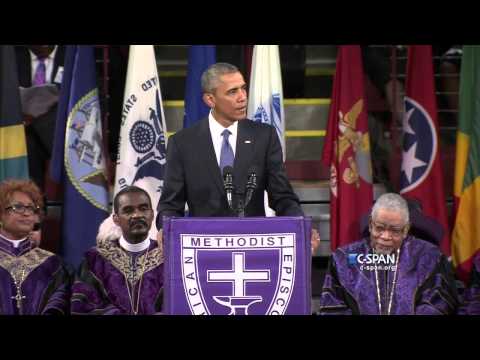

Obama's eulogy for Clementa Pinkney in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015

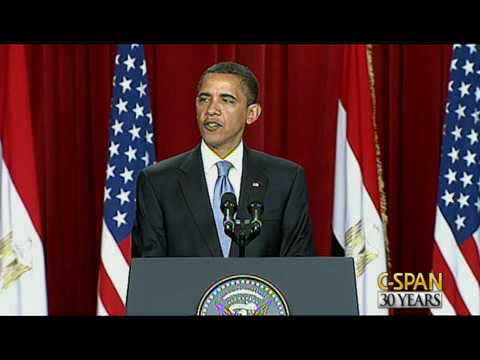

Obama's speech in Cairo in 2009

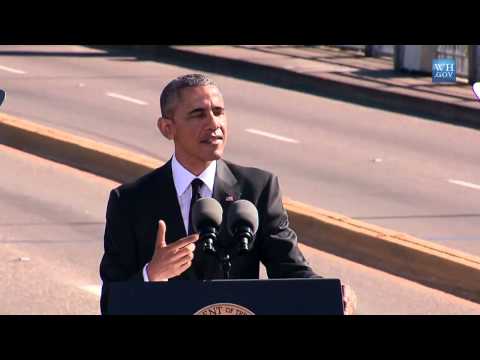

Obama's speech in Selma, Alabama, on the 50th anniversary of "Bloody Sunday"

Book Excerpt: 'We Are The Change We Seek'

By E.J. Dionne Jr. and Joy-Ann Reid

Barack Obama entered the White House in January 2009 confronting as dismal a constellation of circumstances as any president since Franklin Roosevelt: a global financial meltdown that would come very close to being an economic collapse, skyrocketing rates of unemployment, and unpopular wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that showed no signs of being resolved. Despite his fervent campaign promise to ease the country’s political divisions, he discovered that he faced a Republican opposition intent on taking back power by stymieing his program, challenging his mandate to govern, and leaving his dreams of harmony stillborn.

Over time, this meant that Obama had to use his rhetorical gifts to confront and defeat his political adversaries. When circumstances required, Obama could be a highly effective partisan, which further embittered his opponents. Even at his most eloquent, Obama would never win over those who saw him as a dangerous philosophical antagonist.

Yet Obama never dropped the idea that beneath the surface of seething conflict, a country that had elected him as its first African American president was not as torn as it seemed to be.

For his supporters—and, increasingly, as his term concluded, for Americans who had grown weary of the endless partisan wars—Obama remained a figure intent on evoking Abraham Lincoln’s appeal to the “better angels of our nature.” By the time his presidency neared an end, even some among his opponents conceded, sometimes grudgingly, that Obama had a calm fluency they would miss.

Obama always understood that when it came to moving people through the spoken word, he had “it.” He acknowledged as much in 2009 to Harry Reid, then the Senate Majority Leader, after Reid described an Obama floor speech as “phenomenal.” In his memoir, Reid said he would “never forget his response.”

“I have a gift, Harry,” Obama said in a way that seemed quite matter of fact.

Reid insisted that Obama spoke these words “without the barest hint of braggadocio or conceit, and with what I would describe as deep humility.”

The account was published after Obama had become president and Reid, the loyal Democrat, may have been going out of his way to make sure the new president was not seen as arrogant in his certainty about his eloquence. Yet there was a plausibility to Reid’s claim because Obama’s cool detachment often allowed him to tote up his own list of virtues and shortcomings dispassionately. He had simply concluded that being able to persuade, move, and inspire counted as one of his most important assets. He was right about this.

It is surprising that rhetorical genius is not and has never been essential to a successful presidency. Over the last century, the list of presidents we mark out as especially gifted speakers is not long—Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and Obama.

Roosevelt and Kennedy belong on the list not only because they spoke powerfully, but also because each mastered a new medium that had come to dominate politics—radio in FDR’s case, television in JFK’s. The demands of the two were different. Radio was warmly intimate, television friendly toward the coolly ironic. Reagan, liberals would always say, profited from his acting skills and from years on the speaking circuit, but he also excelled because he knew his own mind and had a clear sense of where he wanted to move the country. Clinton shared with Reagan a gift for making coherent arguments and the sure knowledge that making those arguments again and again was a central task of a successful presidency. At the 2012 Democratic National Convention, Clinton used his abilities to press the case on behalf of Obama, once his wife’s bitter rival, winning from the man he now supported a new title, “Explainer in Chief.” Proving that even Obama could sometimes be outshone rhetorically, Clinton’s case for Obama’s reelection was widely seen as more persuasive than the one the president made for himself.

In his choice of oratorical ancestors, Obama’s first love was Lincoln, a sensible choice for a politician from Illinois who had declared his presidential candidacy in Lincoln’s adopted hometown of Springfield, and whose election as the first African American president fulfilled the work of the Great Emancipator. (It did so in a way that might have shocked Lincoln, who, especially early in his career, shared many of the racial prejudices of his time.) Obama had something else in common with Lincoln: a view that the trajectory of American history pointed toward justice and inclusion. Here, Obama also followed Martin Luther King Jr. Lincoln, King, and Obama all believed that the best way to redeem the American promise was to insist that from the country’s origins, this promise was inherent in its founding documents, the Declaration of Independence especially. Obama bound himself to the American past in order to change the future.

There was also a great deal of Roosevelt in Obama, both Franklin and Theodore. Obama, like Clinton, saw himself as the president of a new progressive era that shared in common with the original Progressive Era an imperative to deal with radical economic and social changes. If the early progressives sought to write new rules for a country that had moved from farm to factory and from rural areas to big cities, latter-day progressives would bring order and a greater degree of fairness to a nation even more metropolitan, both suburban and urban, and that was replacing manufacturing work with toil in the technological, scientific, and service economies. In one of the most important speeches of Obama’s presidency, in Osawatomie, Kansas, Obama hitched himself firmly to Teddy Roosevelt’s intellectual and political legacies.

A president who took over in the midst of the greatest economic catastrophe since the Great Depression could not avoid embracing FDR, and he also had FDR thrust upon him. A cover of Time magazine depicted Obama as an FDR look-alike, with a confident smile and a jaunty cigarette holder at his lips. It seemed appropriate for a man who struggled with his smoking habit.

There were certainly some echoes of JFK, particularly in Obama’s generational rhetoric. If JFK was the young voice of the World War II generation, Obama was the first president not touched by the turmoil of the 1960s and he saw himself as liberating the country from many of that era’s assumptions, struggles, and discords. Despite what his conservative enemies often said about him, Obama, like Kennedy, was mistrustful of ideology and could sometimes be very tough on allies to his left. (His Osawatomie speech was, in part, an effort to rekindle their faith in him.)

Perhaps the most unexpected reference point for Obama, given the philosophical divide between them, was Reagan. But Obama’s respect for the Gipper shouldn’t surprise. They shared something unusual in our history: Both had used a single speech to push themselves into the highest reaches of American politics. It is hard to find other politicians who have done the same. William Jennings Bryan with his “Cross of Gold” speech in 1896 came closest.

In Reagan’s case, the speech that launched a political career was “A Time for Choosing,” a broadcast Reagan made on behalf of Barry Goldwater’s failing presidential campaign on October 27, 1964. It is doubtful that the speech changed many minds—Goldwater went down to an historically resounding defeat—but it marked Reagan out as a conservative hero into our day. Using the telling quip, the engaging story, and the apt (if sometimes misleading) statistic, Reagan made modern conservatism sing. By the time Reagan closed (with Lincoln’s “the last best hope on earth” formulation), the millions of conservatives who watched him that night knew that they had found the man who would lead them to the White House. Sixteen years later, he did.

Obama opened his door to the American political imagination with a very different speech, his keynote address to the Democratic National Convention on July 27, 2004. What we remember is its call for national unity, its insistence that “there’s not a liberal America and a conservative America; there’s a United States of America.” Also: “There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.” A country that, it seemed at the time, yearned for unity had found its champion. What’s forgotten is that the speech was also a partisan address with a political purpose. In a sense, it embodied tensions that were present throughout Obama’s rise to office and his time in the White house. Obama always had to go back and forth between his conciliatory hopes and his need to win pitched battles with a Republican party that resisted his overtures.

If Reagan sought to sharpen ideological divisions, Obama saw ideological divisions themselves—especially around social and moral issues—as both the product of Republican strategizing and a drag on liberal and Democratic hopes. The lead-in to Obama’s peroration on behalf of unity, after all, was an attack on Republican divisive designs. “Now even as we speak,” Obama said, “there are those who are preparing to divide us, the spin masters and negative ad peddlers who embrace the politics of anything goes.” Obama was dividing the country in his own way: between those who would divide the country for political purposes and those who would not.

Excerpted from the book WE ARE THE CHANGE WE SEEK by E.J. Dionne Jr. and Joy-Ann Reid. Copyright © 2017 by E.J. Dionne Jr. and Joy-Ann Reid. Republished with permission of Bloomsbury USA.

This segment aired on January 10, 2017.