Advertisement

The Longtime Role Of Race In Memphis Politics

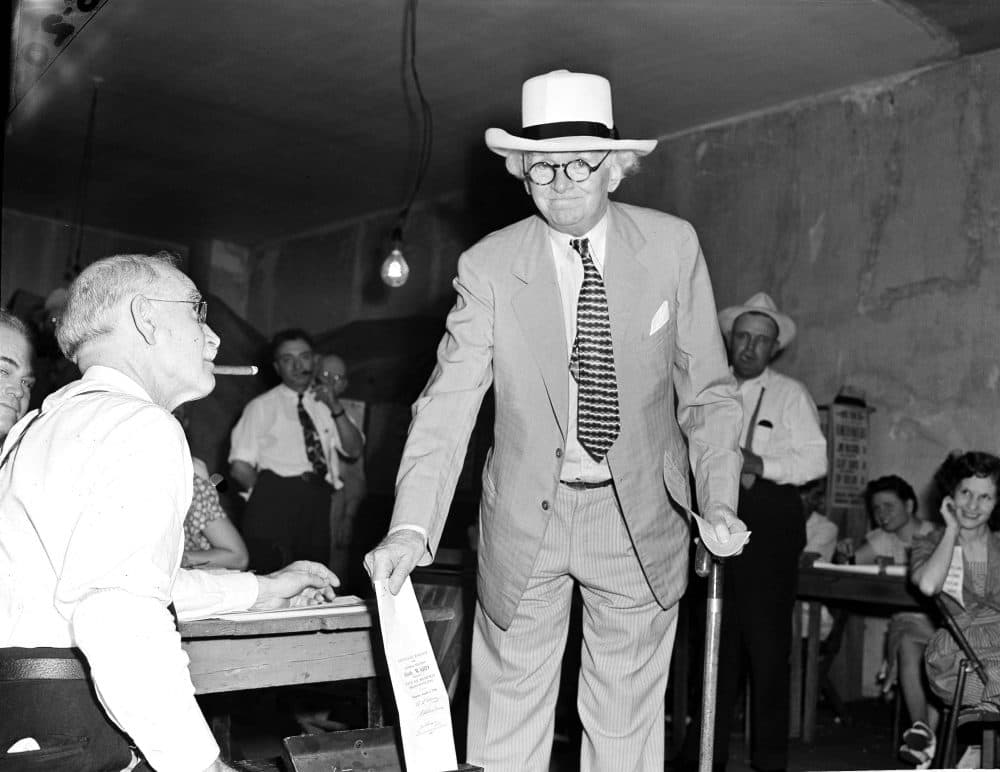

A new book explores how race has shaped politics in Tennessee's second-largest city. It starts with a political boss named Edward Hull Crump, a white man who courted black voters.

Eventually, the city's black population flexed its own political muscle and elected a black mayor for the first time in 1991. Along the way the city saw racial strife similar to many southern cities, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson speaks with Otis Sanford (@OtisSanford), author of "From Boss Crump to King Willie: How Race Changed Memphis Politics" and professor of journalism at the University of Memphis.

Interview Highlights

On Edward Hull Crump, or "Boss Crump"

"Boss Crump was the undisputed political and overall boss of Memphis for almost 50 years. He was only mayor a short period of time, a congressman for two terms, but he ran Memphis and Shelby County and a lot of Tennessee politics for most of his adult life. He was just a political figure that — there's never been one like him before or after."

On enfranchisement in Memphis and how Boss Crump won the black vote

"African Americans were voting in Memphis long before they were in other parts of the south, especially neighboring Mississippi and Arkansas and ... Alabama, but they were voting here. There was a pretty sizable African-American middle class here. He tapped into that, did it well, listened to some concerns of African Americans when nobody else was listening, and it endeared him to the African-American community almost all of his political life.

"One thing that I recount in the book, after he got elected — he was first elected in 1909 — African Americans wanted their own park. They were not allowed to go to white-owned parks, they did not have a park for themselves except for one that black millionaire Robert Church had made for them down on Beale Street. But no other white leader in town would even listen to or entertain the idea of a black park. Boss Crump did, he thought that they deserved one, and so he made it happen despite the reluctance of all the other black officials, and he created Douglass Park, named after Frederick Douglass, that still exists today."

Advertisement

"It [wasn't] until 1990 when African Americans had the legitimate chance, because of the change in population, to elect an African-American mayor."

Otis Sanford, on the political history of Memphis

On whether or not Boss Crump was a racist

"I think there's an argument to be made that he probably was. I say to audiences that he was just a product of his time. I don't think there's any question that he used the N-word more than once. It's been documented and I documented it in the book even though his family says he didn't, but he did. But again, he was a product of his time. He held a council of prominent African Americans in town who respected him, supported him, came to him with their concerns, and he addressed those. So, yes, he was a staunch segregationist, never thought that an African American should hold public office, but you know, you can make an argument that he was a racist, but in those times, pretty much every white person in this area had racial tendencies."

On the election of the city's first black mayor, Willie Herenton, in 1991

"African Americans had long wanted a voice in political life in Memphis, they sought it. But, there was a lot of strain going on, there was a lot of resistance. You know, Memphis didn't get the attention that Birmingham got, or places in Mississippi, for racial violence. They kept the violence down in Memphis. But in terms of African Americans getting into political office, the majority white population that existed in Memphis until 1990, they just were not gonna have it, and it [wasn't] until 1990 when African Americans had the legitimate chance, because of the change in population, to elect an African-American mayor."

Book Excerpt: 'From Boss Crump To King Willie'

By Otis Sanford

The political evolution of Memphis, Tennessee, from the rise of Edward Hull “Boss” Crump to the 18-year reign of Dr. Willie W. Herenton, the city’s first elected black mayor, is one of the most compelling stories in American history. Its numerous characters, primarily elected and appointed leaders and community activists – black and white – were complex, controversial and, in many cases, charismatic. Some, especially Crump, were at times conniving and ruthless. But most were compassionate and forward thinking.

I have no doubt that each of them possessed a genuine love for Memphis. And each contributed mightily to the city’s progress as well as its racial divisions. Crump, for example, was similar in many ways to other big-city political bosses of the early decades of the 20th century, including Tom Pendergast in Kansas City and William M. “Boss” Tweed in New York City, although Crump was never officially linked to any overt criminal corruption.

Arrogant and paternalistic, Crump achieved enduring success as the undisputed boss of Memphis by building an unprecedented and unrivaled coalition of black and white voters at a time when racial segregation in America and black disfranchisement through the South were at their zenith. Still in his twenties when he won his first elected office in Shelby County in 1902, Crump became convinced that Memphis sorely needed a strong leader. It also needed political structure if the city was to grow and prosper. And he considered himself just the man – the only man – for the job.

At the other end of this story is Herenton, a native son of Memphis and arguably the best-educated man to ever occupy the mayor’s office. He is a former Golden Gloves boxing champion and, like Crump, a tall, imposing figure with a persona as big as they come. In 1991, Herenton was simply the right person in the right place at the right time to take advantage of the unified effort by black voters in Memphis to, at long last, elect one of their own as mayor.

Because he was fast with his fists, Herenton as a young man earned the nickname “Duke.” His supporters and admirers later called him “Doc.” But during his time as mayor, his harshest critics – mostly white conservatives from the suburbs surrounding Memphis along with conservative radio talk show host Mike Fleming – often referred to him as “King Willie.” Neither Crump nor Herenton cared much for the monikers their detractors gave them. But the names stuck throughout their respective political careers. Hence the title of this book is “From Boss Crump to King Willie.”

My decades-long desire to tell this story stems from the fact that I have loved Memphis for as long as I can remember. This once barbarous city atop the Chickasaw Bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River has had a profound and positive impact on my life as a journalist. But that’s not the sole reason I love Memphis. The city has a pace, a character and a history that I have long respected and admired. So much has changed politically and socially in Memphis over my lifetime, and the city is arguably not as prosperous as it once was. Peer cities such as Nashville, Charlotte and Louisville have experienced greater economic growth over the last two decades primarily for two reasons – less poverty and less racial strife.

But Memphis in the early 20th Century was a boom town of sorts. It was the center of the cotton trade that made plenty of Memphians wealthy and influential. In addition, African-Americans prospered as business owners and professionals in far greater numbers than those in other major southern cities. And despite an economic decline, Memphis today remains the metropolis of the Mid-South, particularly the surrounding counties in West Tennessee, North Mississippi and East Arkansas – and is the only city of any real size within a 200-mile radius.

I am among those middle-of-the-pack Baby Boomers from a rural community not far from Memphis, who craved a life beyond the gravel roads and cotton fields. Thanks to the newspapers, magazines and television shows that came into our home, I was completely taken by the allure of the big city.

Our farm was located two miles west of tiny Como, Mississippi, and about fifty miles due south of Memphis. I am the youngest of seven children born to Freddie and Bertha Sanford. And our 40-acre farm was the center of my world for the first eighteen years of my life. The cotton produced on several acres of our land was my family’s primary source of income. We grew our own vegetables in a large garden a stone’s throw up the hill from our farmhouse. And we maintained “truck patches” that yielded sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, watermelons – even, for a couple of years, popcorn. We raised several head of cattle, hogs and scores of chickens that roosted in a tin-top hen house just steps away from our back porch. My father was not much of a hunter, but he kept a shotgun and a rifle beside his bed, mostly to ward off the foxes that occasionally preyed on Mom’s prized chickens.

Before Dad could afford to buy a used John Deere tractor to till the fields, we relied on two mules to do the job. My two older brothers were primarily responsible for the plowing, but once I was old enough to help out I gladly did my part on many spring and summer days. When I wasn’t helping with the plowing, I was chopping cotton, picking peas, pulling corn or digging potatoes with my siblings and my mom, who supervised it all.

As I worked on the farm, I constantly fantasized about a life in the city. And that city was always Memphis. Four of my uncles had long since left the farm life in Mississippi and were established Memphis citizens. Three of them had been in the military and, as a result, they got good jobs after they returned home; one worked for the U.S. Post Office, a coveted job for any black person, and another uncle worked at the Memphis Defense Depot, which managed the delivery of supplies for the U.S. Army.

Every trip we made to Memphis to visit them at their homes on well-kept streets in South Memphis and the Orange Mound neighborhood was for me a special occasion. I was dazzled by Memphis’ streetlights, the taxi cabs, the bustling traffic and the fancy stores. I particularly relished our family’s annual trip to the all-black Tri-State Fair, and later the Mid-South Fair, after it was integrated in the mid-1960s. I delighted just in seeing the huge, red-cursive Kellogg’s sign at the cereal plant on Airways Boulevard en route to the fairgrounds. Nothing like that existed in Como. I also loved shopping with my mother at the downtown department stores, especially Goldsmith’s Lowenstein’s and Shainberg’s. It was an added bonus when we took the Number 4 Walker city bus from my uncle’s home on Wilson Street in South Memphis to get downtown.

Memphis is also where we got our news, through the Mississippi edition of The Commercial Appeal newspaper, which was mailed to us six days a week. I started reading the paper every day at the urging of my father, who had little time to spend with it but wanted to keep up mostly with news about baseball. I dutifully kept him informed, but eventually my appetite for news expanded beyond the sports pages.

Excerpted from the book FROM BOSS CRUMP TO KING WILLIE by Otis Sanford. Copyright © 2017 by Otis Sanford. Republished with permission of University of Tennessee Press.

This article was originally published on June 12, 2017.

This segment aired on June 12, 2017.