Advertisement

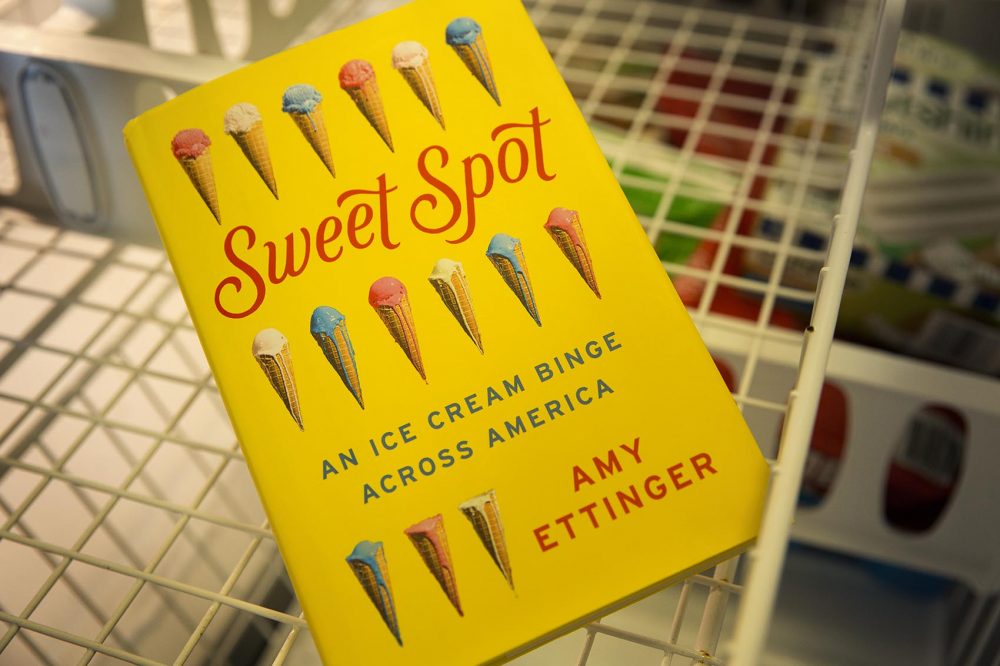

'Sweet Spot' Gives The Scoop On Ice Cream

Journalist Amy Ettinger is obsessed with ice cream. She traveled from coast to coast to visit stores, farms and soda fountains, and even attended a course in ice cream making at Penn State University to find out more about the sweet treat.

Now, Ettinger (@ettinger_amy) has published what she’s found out in the book “Sweet Spot: An Ice Cream Binge Across America.” She joins Here & Now's Lisa Mullins to talk about the book.

Book Excerpt: 'Sweet Spot'

by Amy Ettinger

I was sitting at an outdoor table at Humphry Slocombe in San Francisco, poised to take my first bite of foie gras ice cream, when I began to wonder if my life might be in danger.

The risks, as I saw them, were twofold. First, and most urgently, there was the fear of food-related aggression. Jake Godby, chef and co-owner of the ice cream shop, receives repeated death threats every time the fatty duck-liver ice cream is on the menu. When the shop first opened in 2008, animal rights activists set up a website called Humphry Slocombe Must Die, which featured a photo of Godby with a red slash across his face. Some even threatened to force-feed him until he died.

What if an animal rights activist saw me with the item, which was exposed inside a crinkly cellophane package, stamped with a bright blue sticker, and labeled Foie Gras Sammie?

No food item is quite as contentious as foie gras, which has been the center of a food fight in the United States and has led to bans, repeals, protests, menacing phone calls, Facebook rants, hurt feelings, lost friendships, and even violence.

Advertisement

The concerns about foie gras center around the ethics of gavage, or the process of force-feeding, and have led to countless articles with existential titles like, “Does a Duck Have a Soul? How Foie Gras Became the New Fur.”

I was sitting about 20 feet from where that menu proudly proclaimed Humphry Slocombe’s fatty duck-liver ice cream. There is no actual Humphry or Slocombe. The shop is named after Mr. Humphries and Mrs. Slocombe, the main characters in a satirical 1970s British sitcom, Are You Being Served? Godby runs the shop with his business partner, Sean Vahey. I’d met Godby six months earlier at his shop on 24th Street. He seemed to embrace his inner schlumpiness, proudly displaying his “I don’t care” attitude in a fraying gray sweater he’d paired with shorts.

Despite the violent threats against him (or maybe because of them), Godby still makes the foie gras. Yes, he has to worry about protesters. On the flip side he’s never had to pay a dime for advertising.

In addition to the sometimes violent emails, the shop receives a tremendous amount of interest—with 20-plus phone calls a day from people wondering how they can get the foie gras (and who are disappointed when it sells out).

Godby warned me that he rarely makes the delicacy because it’s expensive and labor-intensive. He advised me to check the shop’s Twitter feed, which I did daily for six months before finally seeing, “DUCK, yes! Foie Gras ice cream on Ginger (oh) Snap Sammies have returned.” The tweet referenced the often confusing legal wrangling in California about the food item.

California became the first state to ban the production and sale of foie gras in 2012, only to have the ban overturned by a federal judge in 2015. Chefs around the state celebrated by bringing the liver back on the menus. This led to a rash of protesting. Ken Frank, who owns the restaurant La Toque in Napa Valley, told The Huffington Post, “A good share of them talk about shoving a pipe up my ass or down my throat.”

These graphic images were swirling in my mind as I sat and prepared to take my first bite of foie gras ice cream. But the Mission neighborhood seemed sleepy, unaware of or unconcerned about the provocative food item in my hands. Several dog owners even walked into the shop and asked for a spoonful of ice cream for their dogs; I watched a poufy-haired labradoodle lap up a scoop of vanilla.

If my life was temporarily spared of human aggression, I still had to contend with another potential danger: What if the ice cream sammie hooked me on the stuff, like a foie gras gateway drug? Getting addicted could very well happen because of the fat-sugar brain reward complex, abetted by a chewy cookie. A recent bit of research indicated that eating large amounts of foie gras could actually cause death. In 2007 researchers published the results of a study showing that mice developed abnormal protein clumps, known as amyloidosis, after ingesting large amounts of the fatty duck liver. In humans, amyloidosis is a rare disease that occurs when a substance called amyloid builds up in your organs. There is no cure.

If true, it seemed like the ultimate karmic payback.

If I avoided both of these potential outcomes, there was always the serious concern that my vegetarian friends might stop talking to me and would keep their like-minded vegetarian children from playing with my child. Julianna had refused to try the foie gras ice cream, as any smart child would. Still, she could be seen as an accomplice.

Humphry Slocombe is as kid-unfriendly as an ice cream store can be. Godby admitted as much. He unapologetically develops his flavors for adults. “I don’t really like children,” he’d told me. His most famous flavor is the Secret Breakfast, which includes cornflakes and bourbon.

Still, you can’t keep kids away from ice cream, even if you douse it in mystery meat or booze. Every ice cream shop, no matter how adventurous, keeps vanilla on the menu. Vanilla sells better than any other flavor throughout the world. Julianna sat with us, happily eating a vanilla cone, while I considered my first bite.

I had to admit I was apprehensive.

Societal shunning had never before been a factor when I considered my food choices. I eat what I want, when I want. Usually I’m a cautious eater, avoiding foods that could cause illness, discomfort, or offense. It was one reason ice cream has always been my favorite food: When I eat it, nothing is expected of me.

Along with the moral quandary, I wondered how it would actually taste, this mixture of duck liver and ice cream. My husband Dan gazed at me as if I were Diana, the leader of the lizard-alien visitors on the 1980s miniseries V. People change during 12 years of marriage. Your spouse can turn into a stranger, and her taste buds can lead to the ultimate betrayal. Still, I could understand his abject expression and confusion. Dan had married a woman who cooked Tofurky for Thanksgiving and experimented with different recipes featuring Veat, a discontinued mystery meat substitute. Now he was sitting across from me as I sat poised to eat meat-infused ice cream.

The foie gras ice cream was presented between two gingersnap cookies and came in a clear plastic wrapper with a bright blue label. I felt giddy as I unwrapped it, the fear adding to the excitement.

As I put it to my mouth, I could smell the ginger from the cookie. I took the first bite. The foie gras had an incomparable mouthfeel. The duck fat coated the edges of my tongue. It tasted a bit like salted caramel. I held it in my mouth and let it warm up, the slightly gamey flavors now easier to taste.

Dan took a bite. He had a look of complete incomprehension as his brain tried to work out the sensations on his tongue.

“It’s a taste best described as caramel pâté,” Dan said.

Humphry Slocombe has a cookbook that teaches you how to make what you’re eating while you’re eating it. That’s how I know that a home chef would start out by caramelizing half a cup of sugar and adding four ounces of raw foie gras, cooking it in a nonreactive skillet for three minutes. Then add cream, milk, more sugar, and salt, cool the mixture, and puree it in a processor. The mixture is strained, left to cool overnight, and then put into an ice cream maker. At Humphry Slocombe they use a Straus base, add the foie gras to it, sandwich the ice cream between two cookies, and wait for the death threats.

As I took another bite, I couldn’t help but feel a thrill. There was something decadent in eating a treat that so many people would be upset about. The wrath I could incur by simply opening my mouth, chewing, and swallowing made me feel powerful. And maybe that perceived transgression is itself a flavor enhancer, much like artificial coloring can ramp up our experience of “lime” or “banana” in some mass-produced, neon-colored taffy or gum.

Is that why Godby put it on the menu—so he could wield that kind of power? Why continue making food that would anger people? Was it to get attention?

Godby insisted that wasn’t the case, that he was just trying to make flavors that would appeal to his own sensibilities and to those of his friends who are chefs. “We don’t do anything for the sake of being weird,” Godby said.

Although Humphry Slocombe put out a cookbook with exacting recipes for consumers, and in spite of its reputation for defying convention and following its own rules, Godby does not make his own base. He told me he gets it by the truckload from Straus.

Having made my own flavors, I could relate to the desire to experiment and try something no one has done before. Following a recipe, especially one from a pre-made mix, seems both boring and repetitive.

Despite what he says, Godby comes across as a bit of a button pusher who does what he does regardless of others’ reactions. He reminded me of my dad, so uncaring about his lack of fashion sense that he was content to walk around with a slide ruler in his breast pocket. Perhaps you need to have that kind of ego to be a tinkerer and sometimes inventor, either in the kitchen or in the world of engineering. And if people don’t like what he’s made? So what? Godby doesn’t spend a lot of time worrying about it.

“It’s not my job to educate,” he said.

What’s the limit to what’s acceptable with ice cream? I asked.

“There’s a place in London that does breast milk ice cream,” said Godby, the revulsion clear on his face.

He was referring to the Icecreamists, which sold pints of breast milk ice cream labeled Baby Gaga in 2011. Just a few days after going on sale, the ice cream was seized by regulators for safety testing. The Licktators, a UK company that also sells female-Viagra-infused ice cream, brought breast milk ice cream back in celebration of the birth of Princess Charlotte and called it Royal Baby Gaga. Lady Gaga threatened to sue because of the name, expressing concern about the implied association between the Lady Gaga brand and a product that struck her as “nausea-inducing.” Its revival was short-lived, and it’s no longer on the menu.

Breast milk ice cream is one of the few dairy products that does not draw the wrath of animal rights activists. PETA has touted breast milk as a more humane alternative to cow’s milk in ice cream. “If Ben and Jerry’s replaced the cow’s milk in its ice cream with breast milk, your customers—and cows—would reap the benefits,” wrote Tracy Reiman, executive vice president of PETA.

The trend with extreme ice cream shows that one person’s gross-out experience seems to be another person’s gleeful experimentation. It left me wondering about why we are eating more extreme foods. Foods that were considered ridiculous 20 years ago are now mainstream. Hence the migration of bacon off the breakfast menu and into every possible food item, including ice cream.

Dan said eating the foie gras ice cream reminded him of the novel My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki. There’s a scene in the book that describes making ground meat fudge.

“I remember thinking the idea of having meat as part of the sweet is the most revolting thing I’ve ever heard in my life,” said Dan. “It became passé to have bacon in people’s ice cream.”

Dan and I passed the silver-dollar-size sandwich between us, taking tiny bites. Does the ginger cookie make the foie gras taste more savory? That was one theory of the kids who scoop ice cream at the shop.

“If I’d advertised to someone on PETA that I was eating a foie gras ice cream sandwich, they would want to set my hair on fire,” Dan said. “They would be very angry with me.” I looked blankly at Dan’s bald head and wondered if lunacy was a symptom of amyloidosis.

Food that causes such delight and rage is extreme, and it begs the question of why anyone would want to make it or eat it. Freya Estreller and Natasha Case of Coolhaus make the argument that our palates are changing as we explore the umami taste. What’s brought about this taste revolution? They say it’s the melting-pot quality of America—with fusion foods bringing rise to things like a Korean barbecue taco or a sushi burrito.

Now more than ever, our minds and taste buds are primed for unusual pairings.

But a little historical digging proved that theory incorrect. We have a history of unusual ice cream in America that dates back to the founding fathers.

We may have fallen collectively into a vanilla-and-chocolate rut, but we were more adventurous in our flavors during our early years of ice cream eating. First Lady Dolley Madison insisted on ice cream at her husband’s inaugural ball. Her favorite flavor? Oyster. She made the fish into a kind of chowder, with onion and ham, added egg yolks and cream, and froze the entire concoction. The recipe appeared in The Virginia Housewife, by Mary Randolph, in 1824.

Excerpted from SWEET SPOT by Amy Ettinger. Copyright © 2017 by Amy Ettinger. Reprinted with permission from Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

This article was originally published on July 05, 2017.

This segment aired on July 5, 2017.