Advertisement

Is It Possible To Love Too Much? New Book Details Life With Williams Syndrome

Resume

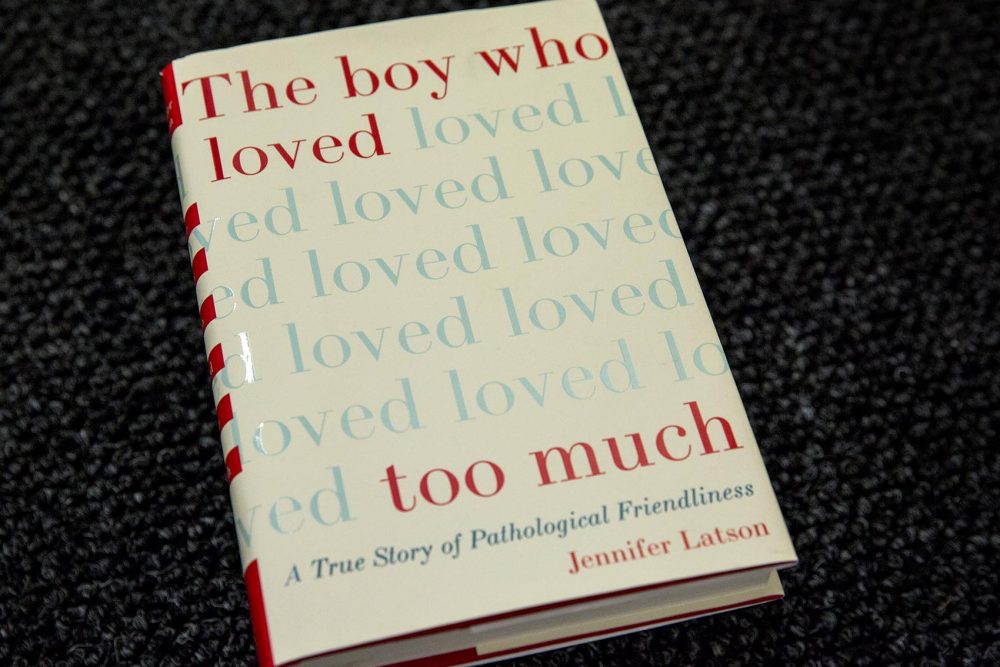

Is it possible to love too much? To indiscriminately love complete strangers? The new book "The Boy Who Loved Too Much" chronicles several years in the life of a boy with a rare genetic disorder called Williams syndrome, which causes developmental delays, heart issues and unabashed affection.

Author Jennifer Latson (@JennieLatson) joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about the syndrome, and the remarkable family she followed.

- Find more great reads on the Here & Now bookshelf

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "The Boy Who Loved Too Much"

Interview Highlights

On Gayle, her son, Eli, and Williams syndrome

"She actually got kind of lucky, although she didn't feel lucky at the time, that her son was diagnosed relatively young, because some people with Williams might not get diagnosed. It's a rare enough disorder — about 1 in 10,000 people has it. Unless a cardiologist happens to notice that you have a rare heart defect that's unique to Williams, a lot of people just could go years and years or their whole lives without getting diagnosed."

On the symptoms, disabilities and abilities of those with Williams syndrome

"Originally Williams Syndrome was actually called elfin face syndrome. So, these characteristics are like what you would see in a storybook drawing of an elf — upturned nose, narrow chin, pointed ears. People with Williams tend to look more like each other than they do their own family members.

"There are symptoms of Williams that are kind of a strange grouping. So you have intellectual disability. It's around what people with Down syndrome have, so an average IQ around 50. But with that intellectual disability, there are abilities. Like, people with Williams tend to be very verbally gifted. They're very imaginative, and they're just very chatty in general, and tend to be great at small talk.

"They have something called hyperacusis, so their sense of hearing is very good, but it's also painful to hear certain sounds because it's so good and, you know, they hear things so loudly. But then as they grow up, it often becomes a source of fascination and that's what happened with Eli. He would watch YouTube videos of people vacuuming their floors. He especially loved this floor scrubber ... Every time I see one at like the Home Depot or something I'm tempted to take a picture and send it to him because he would just be thrilled."

On watching Eli's unabashed affection and how he and his mother handled it

"At first ... I was so just in love with Eli, and he's so adorable and charming and you just want to be around him all the time. But what I really came to appreciate was how amazing Gayle was, and, to me, she really became the hero of this story, because she did go through this struggle every single day, she never got tired of it, that I could tell, you know, she never reached the end of her rope, and she was just like a one-woman anti-hug police. She was just on top of what was going on at all times and just trying to pull her son out of harm's way. But also, her big challenge in the years that I followed him was that kind of awkward transition of, when you're a little boy who hugs everyone, that's adorable. When you're a grown man who hugs everyone, that's assault. So she really wanted to prevent him from being taken advantage of, but also just becoming a pariah. Even when he knew it was wrong on an intellectual level, he just couldn't stop."

On Eli's future

"Well, that was the No. 1 concern for Gayle throughout this whole time that I spent with them is, you know, he's growing physically, he's becoming an adult, he's angsty, but he doesn't have, really, the emotional or intellectual maturity to articulate what he's feeling, and sort of what ends up happening is as he's maturing he's also regressing. So during his early teens, he was throwing a lot of tantrums. He just didn't know how to express what he was feeling, and so he sometimes lashed out with physical violence against his mom and against his grandmother, at one point. That was just really so heartbreaking because he seemed like he was literally beside himself. He just didn't know how to convey or deal with these overwhelming feelings. And as soon as they subsided, you know, he was back to his lovable, cheerful, hugging self. But that was Gayle's concern is, 'How is he ever going to be a mature independent adult, will he ever be independent?' And those are some of the questions that she's still sorting out."

Book Excerpt: 'The Boy Who Loved Too Much'

By Jennifer Latson

Chapter One: Unlocked

July 2011

Gayle didn’t know where to turn. She had been driving east for hours on an unfamiliar highway (I-80) in an unfamiliar state (Pennsylvania), searching with increasing desperation for a place to stop for the night. She had been checking each exit since 9 p.m. But every reputable hotel from Clarion to Punxatawney had been booked full. Now it was past 11. She tapped her crimson fingernails anxiously on the steering wheel.

Twelve-year-old Eli was scribbling with crayons on a notepad in the backseat. His crayons were the fat kind kindergartners used; Gayle bought them because they were easier for him to grip than the slender version. He clutched a red crayon tightly in his fist and drew furious circles, throwing his full weight into the task. Then he lifted the crayon from the page and stabbed it rapid-fire — a manic pointillist creating a fusillade of dots. A few tore through the paper. He lifted his artwork and admired it in the dome light Gayle had left on for him. He chirped with glee, smiling to himself. Then he selected a blue crayon, bent his head over the notepad, and began again. As he worked, he sang a selection of hits from Disney’s The Lion King. Every few minutes, he asked enthusiastically, “When are we gonna get to the hotel?”

Road trips were a source of great excitement for Eli, since they meant a new cast of characters and new social opportunities he wouldn’t find at home. Home was a townhouse in a small Connecticut apartment complex where Eli and his mother lived by themselves. Eli’s father hadn’t been around for years.

From his kitchen window, Eli often watched other boys his age playing in the parking lot. From the French doors overlooking his back patio, he caught glimpses of them shooting basketballs through the hoop behind the subdivision’s communal grass patch. But he’d never joined them. Even if he’d been invited, Gayle wouldn’t have let him go.

Road trips, however, meant stopping at diners and hotels — places where you could meet new people and see unfamiliar vacuum cleaners and overhead fans, to Eli’s great delight. And this had been a nice long road trip: two days north to Michigan and now two days back. Eli squirmed giddily in anticipation of all the adventure still in store.

“We’ll be there soon, Eli,” Gayle said. Her voice was worried, slightly exasperated. She asked him to sing a little quieter.

It was nearly midnight, and Eli was dozing, when Gayle finally found a motel with a vacancy: a low white-brick building near an oil refinery in Clearfield, Pennsylvania. But as soon as she pulled into the parking lot, she was tempted to turn around and keep driving. The warm air drifting through her open window carried the acrid smell of diesel fuel on a cloud of cigarette smoke. The parking lot was filled with work trucks around which men stood in groups, dimly lit by streetlights. Tractor-trailers lined the edges of the parking lot, bordering the motel like a menacing metal hedgerow.

Gayle considered getting back on the highway. If she drove all night they could be home by morning. But she knew she was too tired. They were stuck here at the Clearfield Budget Inn.

Eli woke up when the car rolled to a stop. He surveyed the landscape enthusiastically, oblivious to the seediness of the place.

“I’ve never been here in a long time!” he exclaimed, clapping his hands together.

Gayle stepped out of the car and opened the back door to let him out. She could feel the eyes of the men on her, the only woman in their midst, and on Eli, who was now rocking back and forth on his heels with excitement. Both Gayle and Eli were rumpled from hours in the car. Gayle, a youthful forty-one-year-old, wore a purple camisole and capri-length cargo pants that revealed some of her tattoos. On her back, feathery wings spread outward from her spine. Her left shin was covered with a series of colorful images: on the back, a dragonfly; on the left, flaming dice; on the right, a serpent coiled around a sword; and on the front, a red heart with a banner that said “Eli.”

Her long black hair, usually wavy, had gone limp in the muggy heat. She had pulled it up into a clip, revealing the ear gauges that had stretched dime-sized holes in her earlobes.

Eli wore a black T-shirt and the baggy denim shorts that Gayle had bought at Kohl’s just before the road trip, hoping these wouldn’t split at the seams like his last pair. She described her son as “husky,” but it was his pear shape that made him hard to shop for. Boys’ clothes weren’t designed with this shape in mind.

She ran a protective hand through Eli’s dark curls. His features were those of a much younger child: chubby cheeks, an upturned nose, and a smile so wide it made his eyes crinkle. They were crinkling now. His face was bright with joy, and he tugged at Gayle’s arm, pulling her toward the light, the trucks, the men. She jerked him forcefully in the other direction.

In the sweltering front office, the motel’s owner slid open a thick glass window — bulletproof, Gayle thought. He looked as tired as Gayle felt. She rummaged through her purse to find her wallet, and handed him her credit card. Eli, meanwhile, bounced up from behind her, smiling broadly.

“I’m Eli! What’s your name?” he said, extending a hand to the motel owner. The counter was higher than Eli’s head, but he stood on his tiptoes and strained to reach. The man gave him a quizzical look. Without answering, he reached through the window and shook Eli’s hand.

Turning to Gayle, the motel owner nodded toward the parking lot. “Don’t worry about those guys,” he said. “They’re here for the summer, working construction. They just like to relax out there after work.”

Only slightly reassured, Gayle took the room key.

“He likes me,” Eli declared as they left the office, pointing his thumb toward his own chest.

“I’m sure he does,” Gayle agreed blankly. She was already scanning the row of doors for the number on her key. She slung Eli’s backpack over her shoulder, rolling her suitcase across the uneven pavement with one hand and holding Eli’s hand with the other.

Eli peered at the faces of the men in the parking lot, hopeful that someone would return his gaze, but they looked away when he caught their eyes. One man lit a cigarette; another stubbed one out on the pavement. One man mumbled something too quiet for Gayle to hear. The others laughed.

Apart from the rest of the group, one man sat alone on the sidewalk, his elbows propped on bent knees, his head drooping heavily in his hands. His eyes were closed. Gayle noticed his sinewy arms, his muddy work boots. Maybe he was just tired from a long day, but Gayle’s instincts told her he was more likely drunk or high. She looked for a way around him, but he was on the walkway just in front of her room. There was no other way to go.

She whispered to Eli through clenched teeth, “Do. Not. Say. Anything. To. Him.”

“Why?” Eli replied in an ordinary voice. They were ten feet from the man, and closing in.

Gayle raised a finger to her lips. “Because. He’s sleeping.”

Eli’s eyes never left the stranger. When they were less than an arm’s length from the man, Eli shouted, “Are you sleeping?”

The man raised his head and gave him a dark, bleary look, but didn’t speak. Eli grinned at him. The man dropped his head again. Gayle pulled Eli past, fumbled to unlock the door to their room, and dragged Eli inside. She shut the door hard behind her.

The motel room was outdated — forest-green carpeting, purple-and-green swirled curtains and a pink bedspread — but it looked clean, at least. Gayle checked the mattress ticking for bedbug shells, but found none. There was still a faint smell of smoke inside, which grew stronger when she turned on the air conditioner. She could hear the men’s voices outside, even over the rattling of the AC, and wondered if she’d be able to fall asleep here. Eli, meanwhile, pulled off his Velcro shoes and his shorts, dove under the polyester bedspread, and was snoring before the lights went out.

The next morning, Gayle spent close to an hour looking for the room key, which she had somehow lost. She dumped out the contents of her suitcase, her purse, and Eli’s backpack. Eli chattered happily while she searched, asking questions she only half-answered.

“What are we going to have for breakfast, Mom?”

“I don’t know. We’ll see.”

“We can go to a diner?”

“Maybe. I don’t know what’s around here.”

“I think there’s a diner!”

“Oh, you do?” She couldn’t help but smile at his optimism. He stood at her shoulder, looking up at her expectantly. She set down the backpack she had been rifling through and gave him a hug before continuing her search.

When she kneeled to search under the bed, Eli sprawled atop the shiny pink bedspread and watched her. When she moved into the bathroom, he jumped up and followed her. Gayle crouched to look behind the toilet.

“You can draw a picture of a truck?” Eli asked from the doorway, craning his neck sideways to see her face.

“Not now, Eli. But maybe later.” She opened the cupboard below the sink and looked beneath the extra rolls of toilet paper. She couldn’t really imagine how the key could have gotten under a roll of toilet paper, but she was out of ideas.

“But you can draw it for me?”

“Yes, OK. But later.”

She squeezed past him, back into the bedroom. She pulled the dresser away from the wall in case the key had slipped behind it. It hadn’t. Eli flopped back down on the bed. He cupped his chin in his hand and sighed, growing bored. Gayle re-checked every place she had already looked. The key was nowhere.

Finally she instructed Eli to wait in the room while she flagged down the motel owner. He was also apparently the motel’s one-man housekeeping crew: She saw him a few doors down with a cart full of cleaning supplies. She sheepishly confessed to losing the key.

“I have it,” he said. “You left it in the door last night.”

Gayle’s mind raced with retroactive terror. As if they hadn’t been vulnerable enough already, she’d made it even easier for danger to creep in. She pictured a lineup of the men who must have passed their door while they slept, and the key turn that would have brought them inside. Not only had the door been unlocked, it had been advertised as such. The dangling keychain might as well have been a neon “Welcome” sign.

Gayle shuddered. This was, after all, the central struggle of her life: trying to shelter her son from the world. Eli himself was perpetually unlocked, open, and vulnerable. He carried a welcome sign wherever he went. Gayle was the only barrier between him and everything that lurked outside the door.

She dashed back to the motel room, which she had left unlocked this time by necessity. Eli’s face was pressed to the window. It lit up when he saw her, and behind her, the motel owner. He waved at both of them ecstatically, as if he was being rescued from a desert island and it had been years since he’d seen another human being.

Excerpted from THE BOY WHO LOVED TOO MUCH by Jennifer Latson. Copyright © 2017 by Jennifer Latson. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc, N.Y.

This article was originally published on July 26, 2017.

This segment aired on July 26, 2017.