Advertisement

From Iran To Everest To Space, 'The Sky Below' Recounts One Astronaut's Life Of Adventure

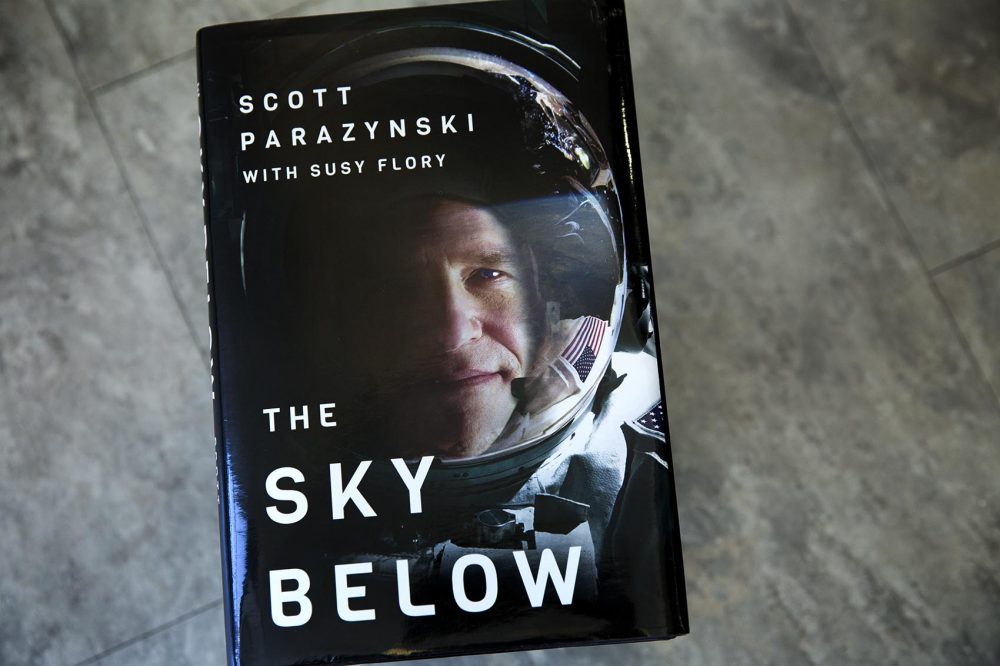

As a teenager, Scott Parazynski's lifelong dream was to become an astronaut. Though he was slightly sidetracked by trying out for the U.S. Olympic team in luge and becoming an emergency room doctor, Parazynski was selected for the NASA space program in 1992. He went into space on five missions and has done seven spacewalks — and also climbed Mount Everest.

Parazynski (@AstroDocScott) writes about it all in "The Sky Below: A True Story of Summits, Space and Speed," and joins Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson to talk about the book.

Book Excerpt: 'The Sky Below'

By Scott Parazynski

Chapter One

On the Shoulders of Giants

"No true adventure is fun while it’s happening." — Dom Del Rosso

EVEREST CAMP 2, 2008

It’s well before sunup on the south side of Mount Everest, and I’m in my tent at Camp 2, twenty-one thousand feet up in the sky, on my way to the summit. The jet stream tears at the thin ripstop nylon walls as it has all night long, but it’s not the bone-chilling cold or shrieking winds driving away any chance of sleep. It’s the searing pain in my back.

My wristwatch alarm chirps at 3:00 a.m. and I struggle out of my bag, determined to ignore my condition. After pulling on my boots and crampons, I cinch down my waist harness until it is vise-tight, like a weight-lifting belt. The pressure helps, and my back feels a little better as we set off in the frigid predawn.

Climbing from Camp 2 to Camp 3 today means over three thousand staggering vertical feet of hard, blue ice, including the Bergschrund, a massive crevasse formed by a migrating glacier separated from the ice on the mountain above. My team includes Kami Sherpa, Ang Namya Sherpa, Chip Popoviciu, Vance Cook, and Adam Janikowski, a good friend I attempted Denali with a few years ago.

Advertisement

After we cross down into the crevasse via fixed lines, we climb up a short, near-vertical pitch of ice to get on the Lhotse Face itself, a long, very steep slope of unforgiving ice leading up to Camp 3 at 24,500 feet. I make it to camp in a very respectable time of four hours, strained back and all.

Camp 3 is the next-to-last waypoint on the route to the top and by far the least comfortable, situated on a few small platforms etched out of the very steep incline of the mountain’s face. Climbers typically confine themselves to their tents except to answer the cold call of nature because it is dangerous to get out and move around without being roped up. There is potential, and historical precedent, for a fatal slip and fall with a catastrophic slide down the Lhotse Face, ending in a 2,500-foot abrupt splatter at the Bergschrund and the Western Cwm below. If we want to make a successful push for the summit, then getting as much rest as possible here and throwing some food down our necks is crucial.

Upon arrival at Camp 3, my tent mate, Adam, and I hurry to settle in well before sunset. When I eventually release the tension in my waist harness to climb into my sleeping bag, I know it isn’t good. The pain and stiffness come back with a fury, and then some. I just need to get some sleep, I keep telling myself. Then I can give it a go and head for the summit in the morning. It feels like someone is hacking away at my lower vertebrae with a Rambo knife. I writhe in my sleeping bag as the pain comes in waves, then recedes. Again and again. It’s tough to breathe.

I work hard to keep myself in great physical shape, but the reality is I’m an aging astronaut, and space missions aren’t kind to the back. I picture my spine like a game of Jenga blocks slowly growing unstable as the game progresses. The average human back’s vertebrae, and the cushioning discs in between, take a real beating from the rigors of a life of upright, bipedal locomotion. These incredible loads on the spine cause disc pressures as high as 230 pounds per square inch.

But I’m a perfect candidate for serious back problems and not just because I’m oldish and getting older. Add in height, six foot three when I’m not slouching, and then factor in the high-g exposures I experienced competing in luge and flying in high-performance aircraft.

Finally, and probably even more important, my multiple spaceflights and spacewalks mean the likelihood of spinal trouble is almost as inevitable as an overloaded, rickety Jenga tower toppling over into a ragged heap. In space, the spine straightens and the intervertebral discs swell when not being compressed by gravity, so my height in space would increase to an impressive six foot, five and a half inches in the absence of gravity—almost worthy of the NBA (regrettably minus the talent). But a return to gravity always meant a return to my original height, or less.

For most astronauts, this zero-g spinal growth is part of the routine, so spacewalking suits are size-adjusted to account for the temporary increase in height. That’s the theory anyway. NASA engineers add about an inch to the spacesuit’s torso, but since it never seems to be quite enough, initially you feel a sense of compression from the slightly too small suit. But after a few minutes your body adjusts, the suit presumably overpressurizing your poor intervertebral discs and squeezing away the excess height.

I know my back pain is a big problem here on the mountain. But my time is running out, and there is a lot at stake. Climbing Everest is all about stacking the cards in your favor, and most climbers aim for the premonsoon season in the Himalayas, before the summer snows arrive, because temperatures are generally a bit warmer. The month of May typically offers a one- or two-week weather window when conditions are at their absolute best. Even so, temperatures average minus 13 degrees Fahrenheit with winds that can crest to 50 miles an hour on a bad day.

Most people don’t know the top of the mountain is so high that it almost penetrates into the stratosphere. The summit feels the full brunt of the jet stream, which can hammer the mountain at speeds approaching 175 miles an hour. By comparison, a tropical storm is considered a hurricane when winds reach just 74 miles per hour, and the winds of a Category 5 hurricane, the most severe, top out at 156 miles per hour. That means these Everest megawinds would be rated as a Category 6 hurricane, or stronger, if there even were such a thing, and temperatures can drop to minus 73 degrees Celsius (or, in Fahrenheit, about 100 degrees below zero).

I am already at Day 59 of my expedition to the top of the world. I’ve planned and plotted with my patented extreme focus, hoping for success but preparing for serious kinks in the road. I’ve made four trips up the harrowing, near-vertical, and not infrequently fatal Khumbu Icefall, a frozen river of jumbled snow and icy cliffs interspersed with dizzying crevasses opening up beneath my feet, sometimes 150 gnarly feet down. I’ve front-pointed my crampons up the hard blue ice of the Lhotse Face higher than I’d ever been before, as the lactic acid burns in my legs and my heaving lungs warn me I am working right up at redline. I’ve fought hard to get up here, where people were really never meant to tread, and I can’t wait around for my back to feel better. With experts recommending spending no more than forty-eight hours at that altitude else your body begins to degrade on its way to death, I have a short window of time. More than anything, I need to rest at Camp 3 and give my back a chance to heal. If that’s even possible.

Adam is asleep in the tent before sunset, a bandana over his eyes and an oxygen mask over his face. He immediately starts snoring, deep gulps of air interspersed with periods of silent apnea. It’s frightening and sounds like a death rattle, but the rational part of my brain tells me it’s just a physiologic condition known as Cheyne-Stokes respiration, normal at these extreme altitudes.

I’d give anything to settle into my own blissful pattern of snores, but instead I spend the next twelve hours tossing and turning in my sleeping bag, trying in vain to reposition my body to something approaching comfort, or at least bring my pain level down a notch or two. I have a few tablets of oxycodone in my medical kit for team emergencies, but at that altitude even a small amount of narcotic medication can suppress respiratory drive, and I reason that breathing is more important than blunting the pain. So I rely on ice, awkward stretches in my sleeping bag, and high hopes of healing through a very long night.

It’s my worst possible nightmare coming to life. At just twenty-four hours from the summit of my dreams, searing pain has kept me up all night, and this morning it’s much worse. How the hell can this be? I writhe in my sleeping bag as the pain comes and goes again. It’s even tougher to breathe now that we’re above twenty-four thousand feet, where the oxygen level is only 40 percent of what you get at sea level. Even though I’ve been on the mountain for almost eight weeks and feel acclimatized to the thin air, it’s still like being slowly choked. But when the pain plunges me into a cold sweat, my thirst for oxygen is of secondary importance.

Every thirty seconds all through the night, I thrash around and instead of recharging, I feel myself sinking down into complete and utter exhaustion. It’s like the worst night on-call I’d ever had in the hospital, racing for my patients all night long, except this time I have a touch of hypoxia, some dehydration and malnutrition, plus a healthy dose of pain. This is not what I planned.

I’m clearly not ready to climb, but at 5:30 sharp, Kami Sherpa and Ang Namya Sherpa unzip the tent flap, pop their heads in, and hand us hot water so we can make tea and eat some oatmeal. They’re anxious to get up onto the upper Lhotse Face in position for a run at the summit from Camp 4, also known as the South Col, our next destination. Will I make it?

Excerpted from THE SKY BELOW by Scott Parazynski with Susy Flory. © 2017 by Scott Parazynski with Susy Flory. Published by Little A. All Rights Reserved.

This segment aired on September 12, 2017.