Advertisement

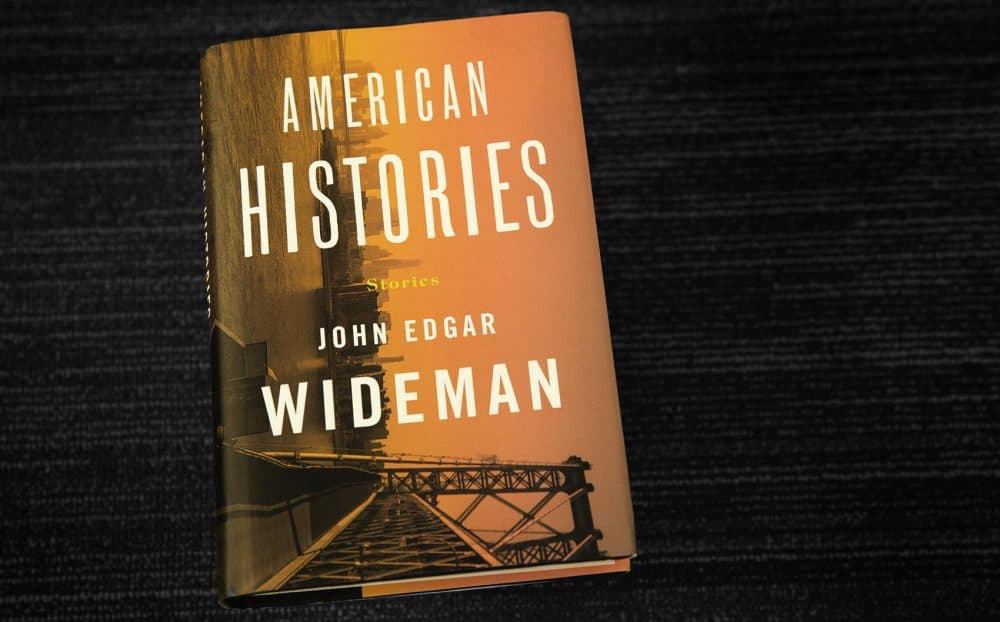

John Edgar Wideman Grapples With America's Continuing Slavery Legacy In 'American Histories'

Resume

Writer John Edgar Wideman's new collection of short stories "American Histories" explores issues of race through historical figures like abolitionists John Brown and Frederick Douglass up through modern times.

Here & Now's Robin Young talks with Wideman about his book.

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "American Histories"

Interview Highlights

On coincidences between himself and the book's narrator, like sharing the same birthday

"It's kind of mysterious, isn't it? There are a lot of coincidences — probably too many to be accidental, and I guess one subject of the book is, 'What is this stuff that you're reading, reader?' I don't know exactly what it is, and I want you to kinda play with me, or read along with me, and maybe puzzling out some of these issues will help us understand the stories."

On referring to Brown and Douglass by their initials in the short story "JB & FD"

"I call people by their initials when they're good buddies, and that's a kinda street thing, too — 'Here comes JF,' or, 'Here comes KC.' It's fun, it's intimate. And so by presuming to call these gentlemen, these historical figures, by initials, already sets up a kind of relationship between the narrative voice and the characters. I just wanted to raise the curtain in a way that said, 'Hey, these people are distinguished, these people lived in another time, but maybe they're also a little bit like you. Let's get right up front and personal.' "

"This racial identification remains a kind of weird sort of mythology and superstition that still haunts us, and still divides us."

John Edgar Wideman

On what he was trying to find through becoming more intimate with Brown and Douglass as characters

"I think I was just throwing out lines, the way a fishermen might throw out lines, or nets, and willing to take whatever I could get. And I wasn't sure whether or not I had a subject for a story, but I did know — and this speaks to your point about information, and Googling — one which I have not quite resolved, and realized it had not been resolved when copy editors and fact-checkers were going over the script. That is, as far as possible, the historical information is accurate. The two men did know one another, they did meet often. They had a kind of a quasi-secret relationship towards the end of their lives, because John Brown was essentially a fugitive, and there was a price on his head. And just before he went to Virginia to actually commence that raid on Harper's Ferry, he did talk with Frederick Douglass. I relied on that for part of the story. I do a lot of work."

On how the book explores race

"My books are not about how it feels to be a black man. My books are about how it feels to be a human being, and part of what I'm trying to sort out is what we mean — what I mean, what you mean, what everybody in the culture means — when they say 'black man,' or they say 'white person.' And this racial identification remains a kind of weird sort of mythology and superstition that still haunts us, and still divides us. And so I'm always writing at some level to sort of loosen that grip of race on our collective imagination — which is not to say race does not exist in one sense, but certainly to call into question the notion that any human being is somehow defined by some quality that's kinda hammered in, or hand-of-God in, before birth."

On working through his own painful personal stories

"The title of my book is 'American Histories,' plural. And as far as I'm concerned, my reading of history is it is a sort of nightmare. It is a sort of nightmare, and I'm trying to wake up from it. And as any nightmare, it's full of much that is unspeakable. And unfortunately from my purview, most people's lives contain incidents, stuff that happens to them, stuff that happens to people they love, stuff that happens in a culture in which they reside, events that are unspeakable, just too painful to bear. And so you're left, as an individual, as a human being, with this unfinished business, and there's a lot of it. And my response to those things in my life is to interrogate them, try to make sense of them, sing about them, cry about them, etc., etc.

"And so, that's my answer. I'm coping. Coping with history, coping with what it means to be alive. How do you talk about the Holocaust? How do you talk about slavery? Probably the best thing to do is just be quiet and hide from it, forget about it. Except, then it jumps up and bites you. Because it's there."

Book Excerpt: 'American Histories'

by John Edgar Wideman

A PREFATORY NOTE

Dear Mr. President,

I send this note along with some stories I’ve written, and hope you will find time in your demanding schedule to read both note and stories. The stories should speak for themselves. The note is a plea, Mr. President. Please eradicate slavery.

I am quite aware, sir, that history says the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery in the United States of America in 1865, and that ensuing amendments extended to former slaves the precious rights and protections our nation guarantees to all its citizens regardless of color. But you should understand better than most of us, Mr. President, that history tells as many lies as truths.

The Thirteenth Amendment announced the beginning of the end of slavery as a legal condition in America. Slavery as a social condition did not disappear. After serving our nation for centuries as grounds to rationalize enslavement, African ancestry and colored skin remain acceptable reasons for the majority of noncolored Americans to support state-sponsored, state-enforced segregation, violence, and exploitation. Skin color continues to separate some of us into a category as unforgiving as the label property stamped on a person. Dividing human beings into immutable groups identifiable by skin color reincarnates scientifically discredited myths of race. Keeps alive the unfortunate presumption, held by many of my fellow citizens, that they belong to a race granted a divine right to act as judges, jurors, and executioners of those who are members of other incorrigibly different and inferior races.

What should be done, Mr. President. Our nation is deeply unsafe. I feel threatened and vulnerable. What can I do. Or you. Do we need another Harpers Ferry. Do we possess in our bottomless arsenal a weapon to demolish lies that connect race, color, and slavery.

By the time this note reaches your desk, Mr. President, if it ever does, you may be a woman. No surprise. Once we had elected a colored President, the block was busted. Perhaps you are a colored woman, and that would be an edifying surprise.

This note is getting too long. And to be perfectly honest, Mr. President, I believe terminating slavery may be beyond even your vast powers. My guess is that slavery won’t disappear until only two human beings left alive, neither one strong enough to enslave the other.

Anyway, please read on and enjoy the stories that follow. No strings attached. No obligation to free a single slave of any color, Ms. or Mr. President.

Excerpted from AMERICAN HISTORIES: Stories, by John Edgar Wideman. Copyright © 2018 by John Edgar Wideman. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This article was originally published on March 21, 2018.

This segment aired on March 21, 2018.