Advertisement

This Massive Model Of The Mississippi River Delta Could Help Restore The Fragile Ecosystem

Resume

Louisiana has lost about 2,000 square miles of coastline in the last 80 years according to estimates — an area about the size of Delaware. Coastal erosion and seawater damage have a lot to do with it.

Scientists have built a massive model of the Mississippi River Delta to discover the best way to restore the fragile ecosystem. Here & Now's Mina Kim learns more about the efforts, and problems facing the delta, from Clint Willson (@clintwillson), director of the Center for River Studies at Louisiana State University.

Interview Highlights

On why Mississippi River Delta wetlands are being overtaken by salt water

"The biggest problem we have is that the river has been disconnected from a lot of the wetlands, and we made that decision as a nation 150 years ago, and then reinforced that to allow the ships and allow the industries along the river to grow. So we basically leveed the river in order to maintain the navigation and protect those communities. The result of that is that we've disconnected the river, and so the river's no longer delivering the water, the sediment, the nutrients back to the wetlands."

"Our coast is really a deltaic coast, so it relied upon the delivery of sediment over thousands of years. And when you disconnect that, you get natural process like subsidence, saltwater intrusion and you get major wetland loss."

Clint Willson

On what kind of damage the seawater has caused

"The biggest problem, is that our coast is really a deltaic coast, so it relied upon the delivery of sediment over thousands of years. And when you disconnect that, you get [a] natural process like subsidence, saltwater intrusion and you get major wetland loss. The vegetation changes types, and then at some point dies off. And so, we've lost almost 2,000 square miles of wetlands, and that's projected to continue over the next 50 years."

On efforts to divert parts of the river and bring sediments back to these wetlands

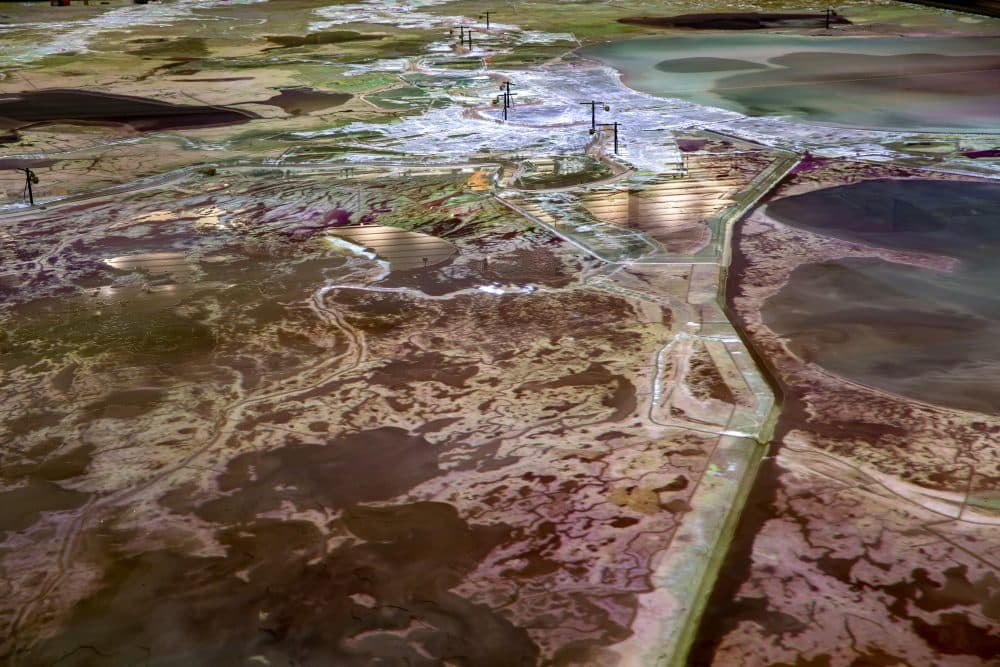

"The state's Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, the lead agency, developed a master plan for restoration and protection. One of the primary project types in their master plan are sediment diversions. The idea is to, in a controlled way, reintroduce the river, and its nutrients and its sediments, back into our wetlands."

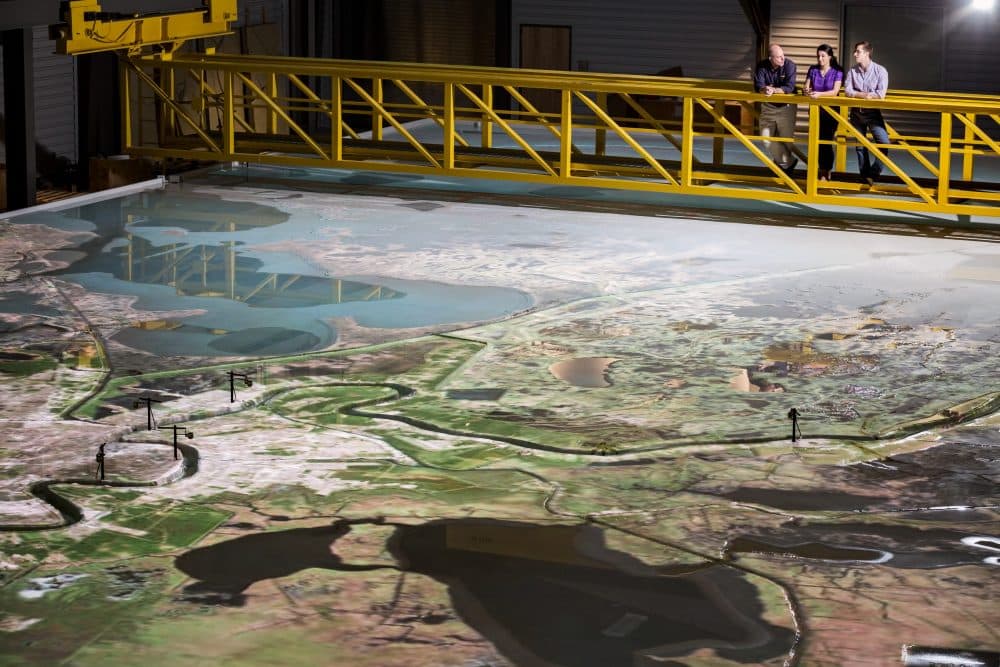

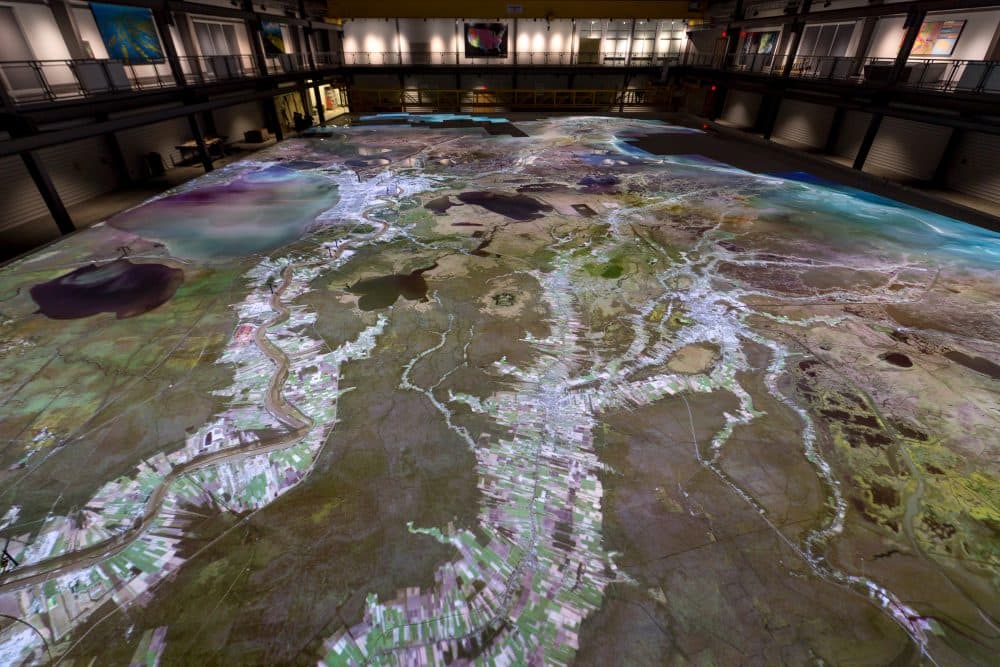

On the large-scale Mississippi River Delta model, and how it will be used

"It's 90-by-120 feet in size, so about the size of two basketball courts side by side, and it covers approximately 190 miles of the lower Mississippi River. And we're able to use the model to look at the flows in the river, the water levels along the river, we're able to look at relative sea level rise, so the combination of subsidence and the Gulf of Mexico rising, we're able to incorporate that into the model, and we're also able to, by using a very lightweight plastic material, we're able to replicate the Mississippi River sand.

"And so when you put all these things together, what we're really doing is looking in a kind of a macroscopic way at how the river is going to respond, whether it's sea level rise, different flows coming down the Mississippi River or most importantly, we're gonna be looking at the effectiveness of river sediment diversions and what impact they have on the river. In other words, are they going to increase or decrease dredging requirements in certain areas? Are we going to increase or decrease water levels in certain areas, because of the sediment diversion. So those are the kinda things that we're gonna study.

"And what makes the model so powerful, really, are two things: First is that we're able to replicate one year on the Mississippi River in one hour on the model, so we can basically go from Jan. 1 through Dec. 31, go through low-flow periods, high-flow periods, when sand moves, when it doesn't move. The second thing that's really so powerful is the ability to let people see how the river responds. How does the sediment move?"

On using the model to determine how diversion efforts will impact other parts of the river

"We want that balance between using the river and its resources for restoration, not disrupting navigation and not increasing flood risk to any of the communities or industries. So yes, we're able to look at, if a river sediment diversion is located around 60 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico, we're able to use this model to see what the impacts might be 10 or 15, 20 miles downstream from that diversion or 15, 20 miles upstream from that diversion."

This article was originally published on May 02, 2018.

This segment aired on May 2, 2018.