Advertisement

'The Mars Room' Tells Story Of Those 'Invisiblized' By California's Criminal Justice System

Resume

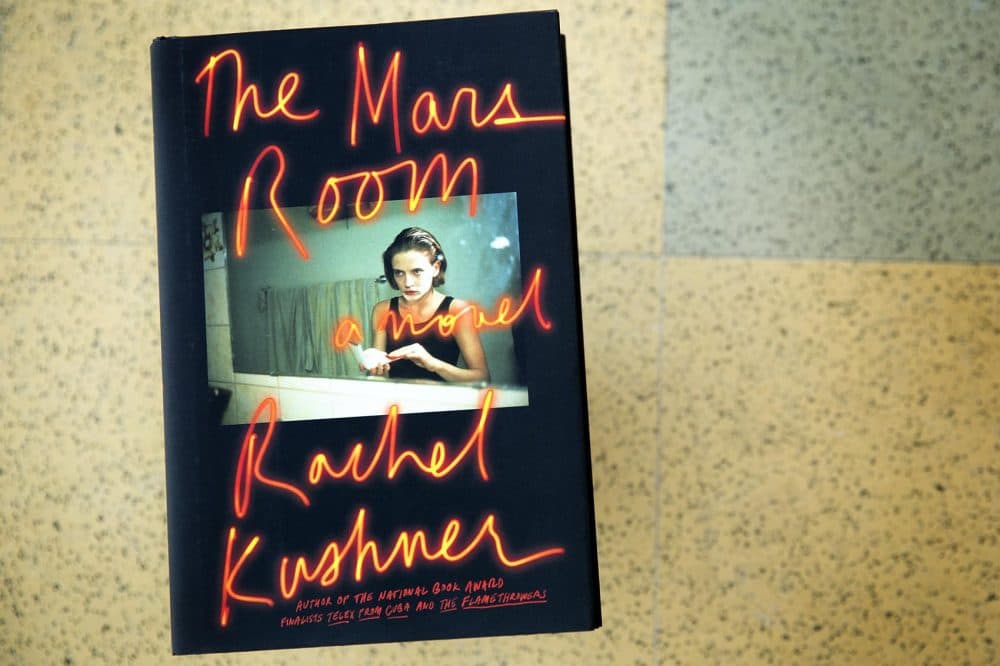

Two-time National Book Award finalist Rachel Kushner's new novel "The Mars Room" centers on a woman who's sentenced to two life terms plus six years in a California prison.

Kushner joins Here & Now's Mina Kim to talk about the book.

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "The Mars Room"

Interview Highlights

On the protagonist, Romy Hall

"It's not so much that my actual biographical life maps one to one to the narrator. She's more like an homage to people I was very close to at that time. And she's from my neighborhood and knew my friends and lived in the world in which I lived. I don't know if it was so much important, but it was the way that I knew to do this book. Because for me it's a book about California. And California is a place where many poor people end up ensnared in the criminal justice system, and once they go there they're invisiblized to middle-class society. And in order to fully inhabit the character and spirit of this woman who goes, I needed to be able to understand her prehistory. And in order to do that with authority, I needed to make her from somewhere that I understood."

On becoming close with people who are serving life sentences

"I know many people in prison. I've become very close to people who are serving life sentences. And I wouldn't really call that closeness a form of research. It's more like, I have a life and in my life I do certain kinds of social justice work that involves people serving life sentences. And many of those people have become mentors to me and I have really valued their expertise and try to honor it in my own work. Hearing from people who've spent a lot of time in what's called administrative segregation in California, which happens to be above death row, was fascinating to me because they know how death row works. And no one who hasn't spent time in administrative segregation or death row itself would know about that, because it's like this inner sanctum sanctorum of the secret proceedings of the prison. And I was stunned to learn that the women down there sew sandbags for flood control in California. So learning details like that, for me, seemed like they could have symbolic importance for letting people in the outside world know that this is a world and that it's very intricate."

On the lessons she learned

"I think one of the most surprising things I learned was when I was trying to advise somebody who was preparing to go before a parole board. And I read all these guidelines that public defenders had put together in terms of training somebody who's going before a parole board to exhibit insight into their crime. And the proverbial insight is of utmost importance to the people on the parole board, in terms of whether or not they think somebody is ready to be released to the public. And I mentioned this to a formerly incarcerated friend, like, 'Oh, I'm helping somebody and I think I can really help them understand their insight.' And this friend of mine said to me: 'If you exhibit perfect insight to a parole board and tell them about your crime and the details of it, and what you were thinking of at that time, and that you understand the horrific impact that it's had on the victims and the loved ones of the victim, you will remind those people of every reason why the state wanted to lock you up to begin with. And so what that did was alert me to this Catch-22, that understanding is not necessarily going to be of benefit to somebody trying to argue for their own release."

On whether chance plays a role in going to prison, and in the lives of these women

"To some degree, yes. The fact is, it is almost entirely poor people who go to prison and serve long sentences there. But within the so-called problematic or unruly layer of society, there are many exceptions, there are many people who do not go to prison and others who do. So inside of a pattern that predominantly ensnares poor people, chance does play a role."

Book Excerpt: 'The Mars Room'

by Rachel Kushner

The trouble with San Francisco was that I could never have a future in that city, only a past.

The city to me was the Sunset District, fog-banked, treeless, and bleak, with endless unvaried houses built on sand dunes that stretched forty-eight blocks to the beach, houses that were occupied by middle- and lower-middle-class Chinese Americans and working-class Irish Catholics.

Fly Lie, we’d say, ordering lunch in middle school. Fried rice, which came in a paper carton. Tasted delicious but was never enough, especially if you were stoned. We called them gooks. We didn’t know that meant Vietnamese. The Chinese were our gooks. And the Laotians and Cambodians were FOBs, fresh off the boat. This was the 1980s and just think what these people went through, to arrive in the United States. But we didn’t know and didn’t know to care. They couldn’t speak English and they smelled to us of their alien food.

The Sunset was San Francisco, proudly, and yet an alternate one to what you might know: it was not about rainbow flags or Beat poetry or steep crooked streets but fog and Irish bars and liquor stores all the way to the Great Highway, where a sea of broken glass glittered along the endless parking strip of Ocean Beach. It was us girls in the back of someone’s primered Charger or Challenger riding those short, but long, forty-eight blocks to the beach, one boy shotgun with a stolen fire extinguisher, flocking people on street corners, randoms blasted white.

If you were visiting the city, or if you were a resident from the other, more admired parts of the city and you took a trip out to the beach, you might have seen, beyond the sea wall, our bonfires, which made the girls’ hair smell of smoke. If you were there in early January, you would see bigger bonfires, ones built of discarded Christmas trees, so dry and flammable they exploded on the high pyres. After each explosion you might have heard us cheer. When I say us I mean us WPODs. We loved life more than the future. “White Punks on Dope” is just some song; we didn’t even listen to it. The acronym was something else, not a gang but a grouping. An attitude, a way of dressing, living, being. Some changed our graffiti to White Powder on Donuts, and many of us were not even white, which becomes harder to explain, because the whole world of the Sunset WPODs was about white power, not powder, but these were the beliefs of not powerful kids who might end up passing through rehab centers and jails, unless they were the chosen few, the very few girls and boys, who, respectively, either enrolled in the Deloux School of Beauty, or got hired at John John Roofing on Ninth Avenue between Irving and Lincoln.

When I was little I saw a cover of an old magazine that showed the robes and feet of people who had drunk the Kool-Aid Jim Jones handed out in Guyana. My entire childhood I would think of that image and feel bad. I once told Jimmy Darling and he said it wasn’t actually Kool-Aid. It was Hi-C.

What kind of person would want to clarify such a thing?

A smart-ass is who. A person who is safe from that image in a way I was not. I was not likely to join a cult. That was not the danger I felt in glimpsing the feet of the dead, the bucket from which they drank. It was the proven fact, in the photographed feet, that you could drink death and join it.

--

When I was five or six years old I saw a paperback cover in the supermarket that was a drawing of a woman and her nude body had two knives coming out of it, blood pooling around her. The cover of the book said, “Killed Twice.” That was its title. I was away from my mother, who was shopping somewhere in the market. We were at Park and Shop on Irving and I felt I was not just a few aisles away but permanently sucked out to sea, to the engulfing world of Killed Twice. Coming home from the market, I was nauseous. I could not eat the dinner my mother prepared. She didn’t really cook. It was probably Top Ramen she prepared for me, and then attended to whichever of the men she was dating at the time.

For years, whenever I thought of that image on the cover of Killed Twice I felt sick. Now I can see that what I experienced was normal. You learn when you’re young that evil exists. You absorb the knowledge of it. When this happens for the first time, it does not go down easy. It goes down like a horse pill.

Excerpted from THE MARS ROOM by Rachel Kushner. Copyright © 2018 by Rachel Kushner. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This article was originally published on May 03, 2018.

This segment aired on May 3, 2018.