Advertisement

Jell-O Has Delighted Many American Households. But For One Family, It Was A Curse

Editor's Note: This segment was rebroadcast on July 24, 2019, after "Jell-O Girls: A Family History" was released in paperback. That audio is available here.

Jell-O was a staple of American households for decades and made a fortune for author Allie Rowbottom's family. But her family was also haunted by alcoholism, suicide and cancer.

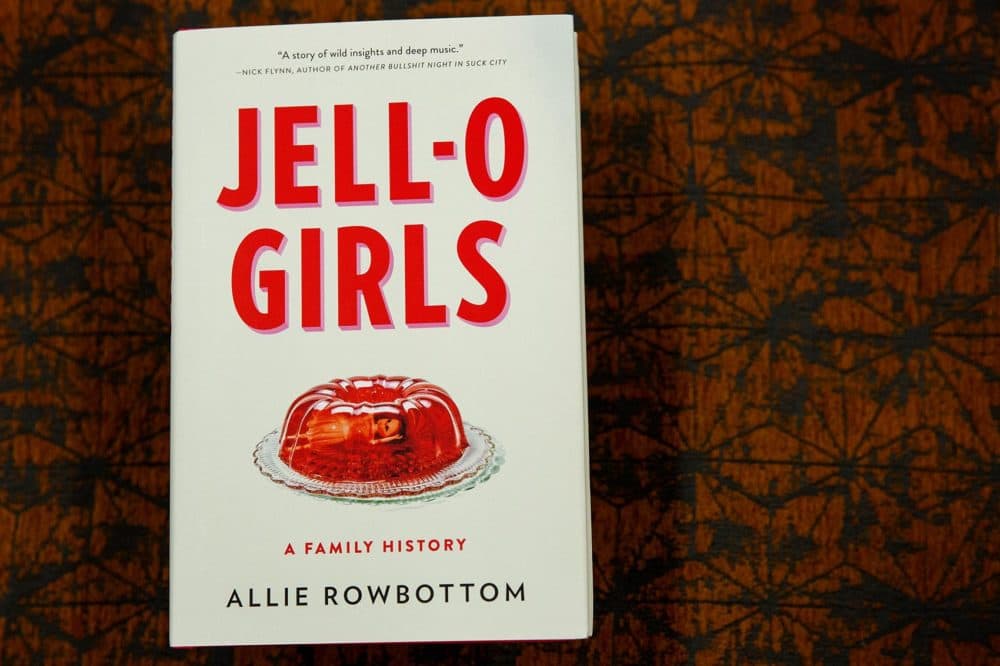

Rowbottom (@allierowbottom) writes about that duality in "Jell-O Girls: A Family History," and joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about her memoir.

Interview Highlights

On her mother’s death and how she avoided Jell-O until she was dying of cancer

"At the end of my mother's life, she accepted it, but for much of her life, she avoided Jell-O, seeing it as sort of a symbol of patriarchy on a broad scale, but also of her own family's struggle against patriarchal forces and against what they thought of as a Jell-O curse.

"At the end of her life, when it turned out that Jell-O was the only thing that she could stomach, it was this sort of grim irony. Unfortunately, it wound up being the last thing she ever ate."

"At an age where America was really privileging science and technology, it compelled its audience."

Allie Rowbottom

On the history of Jell-O, its ingredients and uses

"Jell-O's marketing really took hold around the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Many American women were losing a lot of their help in the kitchens to factory work that was more lucrative and probably more rewarding in a lot of senses for people who had previously worked in the kitchens of the middle classes.

"Many American women were finding themselves unsure of how to prepare the recipes that they had grown used to eating, but Jell-O came around and sort of had a double hook, in that it was so easy to prepare, but it was also this new, scientific food. At an age where America was really privileging science and technology, it compelled its audience.

"I think it's made more from boiled hides and skins. But at the time, it was rendered from hooves and bones. ... It could be a breakfast, but it was also a salad, but then it could also be a dessert, so it was very versatile, and it really molded itself, if you will, to people's palates."

Advertisement

On writing about her mother after her death

"It was a really moving experience, honestly. I started this book before she died, but it really wasn't until after she died and I experienced grief and loss that I really understood why she had behaved the way she had for most of her life. For example, on birthdays and Christmases, she would send us presents from her own dead mother, and I always found that strange. And now I completely understand it.

"I think all of my mother's behaviors could really be traced back to that initial loss."

On how her mother had wanted to write a memoir that also included the theme of patriarchy

"She had tried for much of my life to write a memoir of her girlhood and adulthood and to braid in this idea of the curse of patriarchy and how it connected within her family and how it probably in her mind connected in most women's lives."

On a mysterious illness that plagued a group of young girls in Le Roy, New York, where Jell-O was invented, and how she and her mother believed the sickness to be connected to the town’s silencing of women

"The girls were initially a mystery and later diagnosed with conversion disorder and mass psychogenic illness — conversion disorder being the conversion of emotional trauma or stress into physical symptoms, and then mass psychogenic illness being ... the mysterious spread of these symptoms through groups with no real reason for it having spread.

"My mom really felt that these girls were very obviously responding involuntarily to a culture that was particularly strong in Le Roy of silencing women. And so, as she and I both knew through our own experiences, when one's voice is silent, often times the body finds other ways to speak."

On her and her mother’s own mysterious illness that partially paralyzed their hands, and its relation to patriarchy

"I think that, like the girls in Le Roy and like my mother before me, a lot of my struggle traced back to not feeling free to speak. Once I started to speak and express myself in therapy and to learn that it was safe to do so, my symptoms became less present."

"I think it just proves the importance of work by women that challenges the norms that we still live with and norms that would see us stay silent."

Allie Rowbottom

On the response to the book

"I've heard a lot of wonderful stories of people's childhood relationships with Jell-O. I've been gifted recipes. I've been gifted old cookbooks. A lot of people don't see this book as portraying Jell-O necessarily negatively.

"I will say that there are some people, maybe connected to Le Roy, who don't feel great about the book. It's a challenge as a writer to write honestly of a place or a person, but also to not portray it as any one thing.

"It's a constant challenge, I think, probably with anyone who puts a book out into the world, but for this book in particular, to stand behind my work and to stick to my guns when there are many who are coming forward — or some who are coming forward, I should say — who are proving the point of the book ... and trying to shut me up.

"I think it just proves the importance of work by women that challenges the norms that we still live with and norms that would see us stay silent."

Book Excerpt: 'Jell-O Girls'

by Allie Rowbottom

In the early 1960s, Jell-O’s age-old selling point as a national beacon of stability, a staple of nuclear-family dinner tables and affordable “fancy” dishes, flickered and surged dramatically. This wasn’t success: this was the gasp of a flame preparing to die out. The country was in flux, teetering on the latter half of a century that had inflicted trauma on the collective psyche. And now, America was in the middle of another war, facing stirrings of civil disobedience. Change was filtering into the country’s unconscious, hinting of the upheaval soon to roil up, a fever from beneath our national skin. Advertisements responded as best they could. Best to hunker down for now, they urged, their messages achingly upbeat, like forced smiles: best to lean on routine and familiar family structures. Best to serve a delightful and wholesome Jell-O mold tonight. In new mixed-fruit, blackberry, and orange-banana flavors!

More than ever, family was a focal point. The family unit was to be stressed, preserved. So even as Jell-O advertisements kept a toe in the water of the diet conscious, they also revolved around the nightly dinner table, reflecting the indulgent side of America’s cultural ethos. There are people who like to eat, one television spot began, speaking over a montage of different American dinner tables where a clan of Maine lobstermen shells the fruits of their labor, an Italian matriarch serves pasta, and a third family celebrates the oldest son’s return from military service by heaping his plate with food. There’s Always Room for Jell-O! the ad proclaims, even for those stuffed full of America’s bounty.

America’s tenuous bounty. By 1964 the beacon had gone out for LeRoy. In a move that would change the town forever, General Foods closed the original Jell-O factory and relocated manufacturing from New York to Delaware. Families who’d worked for Jell-O for generations were suddenly faced with an impossible choice: leave the only home they’d ever known, or lose their only job. Many LeRoy natives, so betrayed by Jell-O’s departure, vowed never to buy it again. They knew what they’d had was special.

LeRoy’s sudden crisis reflected a larger, national one: looming cultural and economic upheaval, an identity in limbo. Like many small towns in America, LeRoy was actively losing the jobs that had made it prosperous. They knew no magical mass-produced cash cow would come their way again. And although Haloid Xerox, Lapp Insulator, and Eastman Kodak, staples of Rochester’s economy, mercifully stayed put (for the time being, however: Kodak laid off thousands of employees in 1997 and declared bankruptcy in 2012), the decampment of Jell-O marked the beginning of the end of the region’s boom time.

* * *

The decline has been significant since then but drastic in the last decade. As recently as the 1980s, the median income in LeRoy was nearly 9 percent higher than the national average. Since then it has fallen to well below the national average. The stress of unemployment, specifically the loss of the factory work that once helped it prosper, performs itself in LeRoy through the transformation of the town’s once-formidable homes—Gothic and Greek revival houses with butler’s pantries and enough bedrooms for large families—into multi-unit rental properties. Families, too, have changed, their structure altering alongside the disappearance of factory work. In 1980, LeRoy had fewer single mothers than the rest of the country. But in the past thirty years, that number has surpassed the national average.

The absence of strong father figures and nuclear families in LeRoy would become, in 2011 and 2012, a talking point for journalists and doctors investigating the origins of the LeRoy girls’ sickness. Financial instability and tenuous support systems were eventually targeted as key contributors to the girls’ condition, which was, doctors argued, fundamentally rooted in deep insecurity and stress. But stress and insecurity were quickly ignored in favor of older, more familiar narratives concerning the dangers of female desire. Watered-down versions even appeared in popular novels such as Katherine Howe’s Conversion and Megan Abbott’s The Fever, both fictionalized accounts of the girls’ illness. Where Howe’s novel posits that the tics and twitches come from the history of the town (moved, in the novel, to Danvers, Massachusetts) as a site of witch trials, Abbott’s The Fever frames the outbreak as a repercussion of the afflicted girls’ burgeoning sexuality and the “increased physical vulnerability” that accompanies their transition from children into adolescents. Abbott suggests this change is “a kind of witchcraft,” but by the end of the novel, the characters’ symptoms are revealed to have been caused less by magic than by a mélange of poison— administered by one particularly jealous girl—deception, and mass psychogenic illness, which Abbott barely defines. The whole fever, it turns out, revolved primarily around competition for the attention of a popular boy.

This, of course, is a common story, that of malingering and manipulative women, their competition and precarious sexuality, which must be tamped down, contained, lest it lead to sickness, crime, catastrophe. This is also the story that the mothers of the real LeRoy girls rejected. Their daughters weren’t faking, or poisoning each other; they weren’t insanely jealous or sexually deviant. Nor were they victims of unstable home lives. Many of the mothers found themselves in the position of wearily defending their ability to single-parent— or to parent despite their own illness—asserting with understandable defensiveness that they, and they alone, could handle motherhood, breadwinning, and the onset of this outbreak. They’d always had to, after all, and their daughters were stronger for it—not weaker. So there must be a physical origin to the girls’ condition. Emotional trauma couldn’t touch these girls, their mothers argued, because these girls had been raised by women strong enough to bear it.

Emotion as weakness, desire as instability, trauma as failure: these correlations came up often in regard to the girls of LeRoy. These girls were strong, mothers insisted, not traumatized. But the two are not mutually exclusive, my mother argued, even as she wistfully doubted all the girls would get the help they needed. “They need to express themselves,” she said, “but they don’t live in a culture that teaches them to.” Trauma needs to be spoken, she said, it needs to be heard. The girls’ conversion disorder was essentially a coping mechanism, a system their minds found to tolerate the intolerable until they were able to find help. Disorder is, she said, in its own way, an ingenuity.

Excerpted from Jell-O Girls: A Family History. Copyright © 2018 by Allie Rowbottom.

Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York. All rights reserved.

This segment aired on August 15, 2018.