Advertisement

Biography Examines Prolific Career Of Choreographer Behind 'West Side Story'

Dances like the elegantly "rumbling" teenagers in "West Side Story" are the legacy of Jerome Robbins, who also created the memorable choreography in "Fiddler on the Roof," "Peter Pan" and "The King and I."

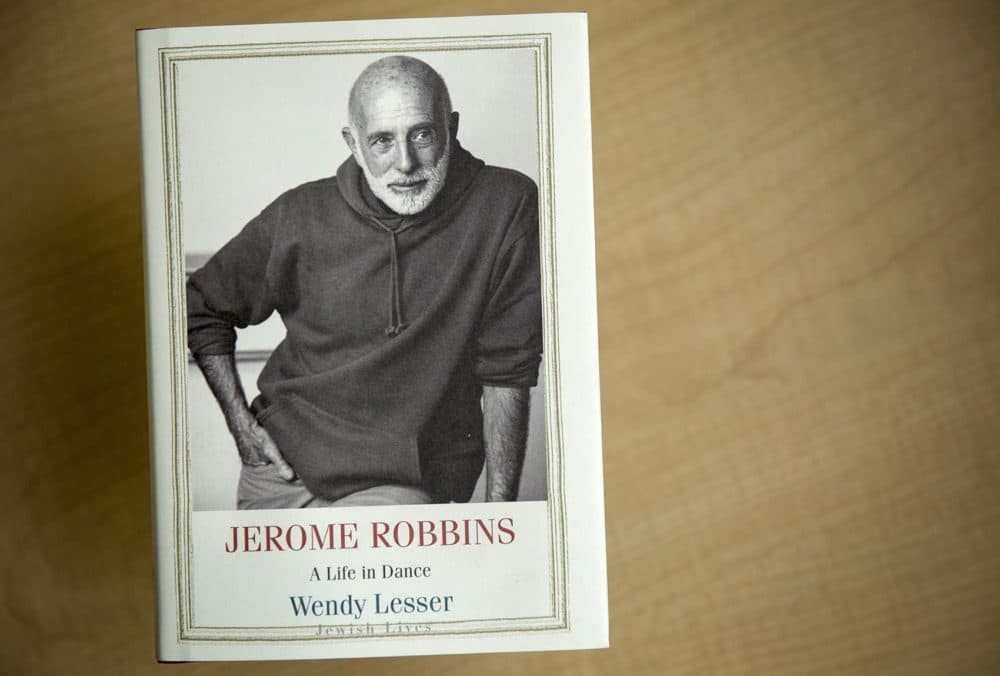

Here & Now's Robin Young talks with Wendy Lesser, author of "Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance," who says Robbins' work in ballet — which has been at times overlooked — was equally as strong as his work on Broadway.

Watch: Performances Of Robbins' Choreography

Book Excerpt: 'Jerome Robbins: A Life In Dance'

by Wendy Lesser

He may well have been the most hated man on Broadway. “Mean as a snake,” said Helen Gallagher, a performer who worked with him on several shows, and her words echoed the abundant testimony of others. A few dancers loved him deeply, and many more admired him, but almost all of them feared him. In particular, they feared the vicious outbursts that would tear them down to nothing, reducing them to a humiliating puddle of tears and sweat. He felt he had to break everything down in order to build it up in a better form. The performers understood that. But it was hard if you were the material being shaped.

A much-repeated story from one of his Broadway shows (probably Billion Dollar Baby, though it’s been attributed to several others) points to the intensity of the collective resentment. During one rehearsal, Robbins was addressing the dancers and singers as they stood on the stage of the theater. He had his back to the orchestra and the rest of the auditorium, and the performers were ranged around him, facing him. As he spoke, he stepped backward. Then he stepped backward again, dangerously close to the edge of the stage. Nobody said a word. He took another step back and fell into the pit, and not one of them came to his aid. Their silence, in the close-knit world of stage performers, was tantamount to a village stoning.

Advertisement

If you had asked Jerome Robbins why he acted the way he did, he would have said it was all in service of the art. And for the most part it was. When he told the dancers playing Puerto Ricans and whites that they could not associate with members of the opposite gang during the entire rehearsal period for West Side Story—and when, to exacerbate tensions between the two groups, he circulated scurrilous gossip about Jets among Sharks and about Sharks among Jets—he did so in order to create the level of manifest hatred that he felt the show demanded. Similarly, when he jointly auditioned the two actors who eventually got the central roles of Maria and Tony, he first called them onto the stage separately. To Carol Lawrence, he said, “I want you to get lost on the stage somewhere, so he can’t see you. I’m going to bring him in and let him do ‘Maria.’ After that, if he can find you, do the balcony scene. If he can’t find you, you don’t have an audition.” Once she had hidden herself on a grating fifteen feet above the stage, he brought in Larry Kert and told him the same thing. The poor guy sang his heartfelt song, meanwhile frantically glancing around the stage and not finding his Maria anywhere. Just as he was about to give up, his co-star hissed, “Tony!” and he turned, saw her, and clambered up the rickety ladder to her side, where they finished the scene in an overflowing spirit of intimate relief. Leonard Bernstein— who, as the composer, had been privy to this scene—walked from his seat in the audience down to the front of the stage and said, “That is the most mesmerizing audition I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Rehearsals were nightmarish experiences, with everyone exhausted by the long days, forced to go through ten or twenty versions of a single scene as Robbins worked out what he wanted. Recalling her role in the ballet Age of Anxiety, Tanaquil Le Clercq complained that Robbins “rehearsed it to death . . . he changed it all the time,” working her and the other dancers until they were all “goofy with fatigue.” The choreographer thought nothing of exposing his performers to physical pain, as when he made one of his gang members lie on the blisteringly hot New York City pavement during the filming of West Side Story: “Where do you think you’re going?” Robbins snarled at the dancer when he tried to get up between takes. At other times he would freely ladle out insults, along the lines of “I thought you were a better dancer than that.”

And he was no kinder to his actors. When, during the out-of-town tryouts for Fiddler on the Roof, he gave notes to Austin Pendleton about his role as the son-in-law Motel, he sneered at this once-favored protégé, “I don’t know what’s happened to you. I had to walk out during the wedding scene last night because the idea of that girl being forced to marry you was so revolting. You’ve lost that tenacity—you’re not worth her time.” Years later, reflecting back on this moment, Pendleton admitted that Robbins “was seeing a weakness in me he had never seen, a complacency, a limpness. It was cruel but it addressed exactly what had to happen between me and the role. He was right.” And Robbins’s own comments about his cruelty contained much the same defense: “I blow, but it only happens when the person isn’t doing the job I think they should and not giving back as much as I’m putting into it.”

What he was putting in was his whole self, along with everything he knew about the world and its people and the emotions that governed their lives. That was the novelty of Jerome Robbins’s idea of performance, whether it was a Broadway show or a ballet for one of New York’s well-regarded dance companies. They were not just entertainments, in Robbins’s mind; they were not just finely wrought products of a traditional art form (though they were both those things as well). Those patently artificial forms—the American musical, the court-derived ballet —were for him the expressions of a felt reality, and if the actors and dancers putting them on could not feel them as real, then the artworks would be worth nothing in the end. “I emerged a different person” was how Austin Pendleton described his response to the last-minute critique of his Motel part, and that was what Robbins wanted every time: complete transformation. He wanted it of himself just as much as, and perhaps more than, he wanted it of everyone else. Observing that he was “just murder to work with,” Trude Rittman, the rehearsal pianist for Billion Dollar Baby, said her complaint “was not that he did it to me, but he did it to the kids and he did it to himself. . . . This man constantly murdered himself. He was so high-strung and tormented.”

Excerpted from the book JEROME ROBBINS: A LIFE IN DANCE by Wendy Lesser. Copyright © 2018 by Wendy Lesser. Republished with permission of Yale University Press.

This segment aired on October 17, 2018.