Advertisement

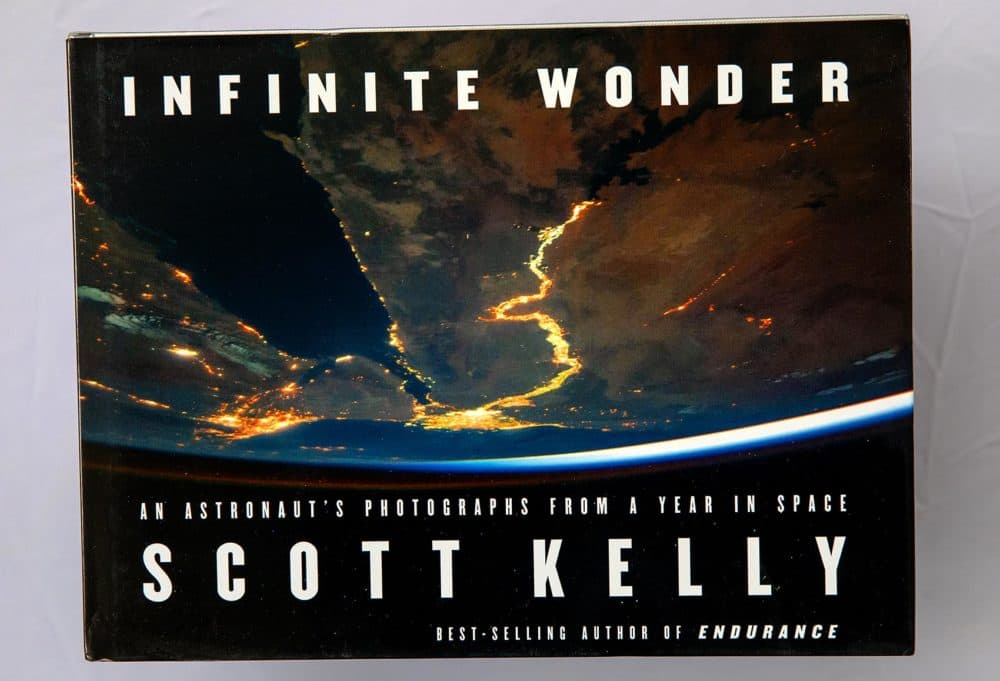

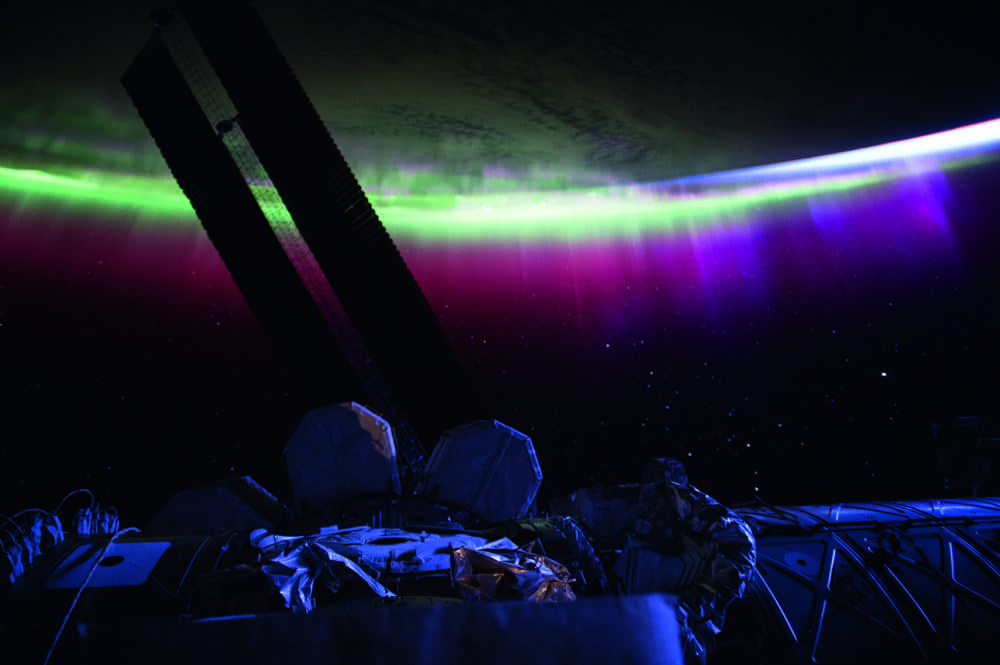

Astronaut Scott Kelly On Capturing Earth's 'Infinite Wonder' From Outer Space

Resume

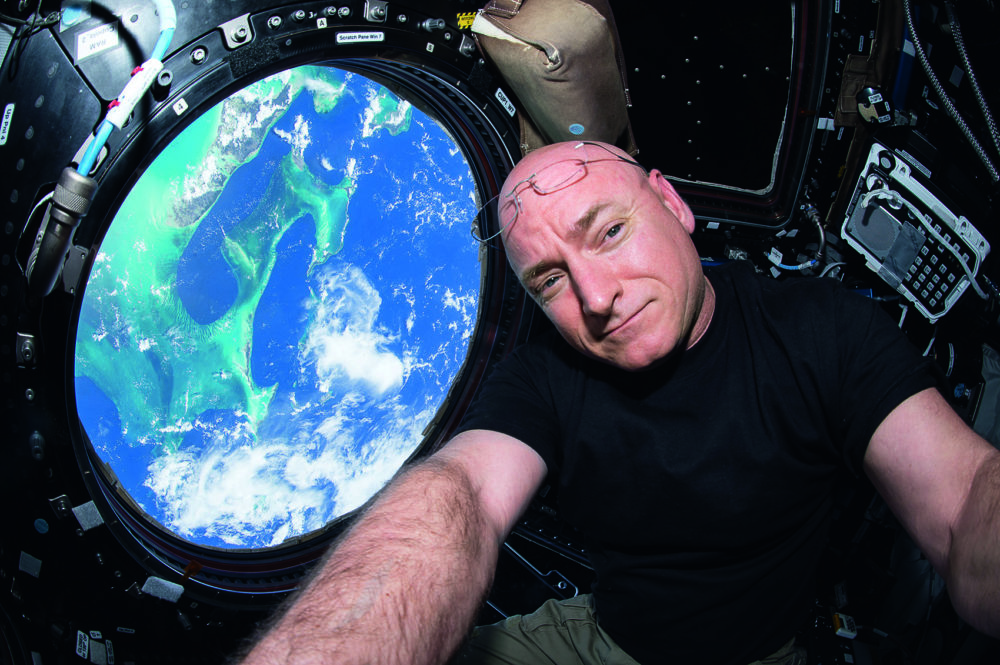

Scott Kelly holds the American record for the most consecutive days in space, spending 340 of them in orbit aboard the International Space Station before returning to Earth in March 2016.

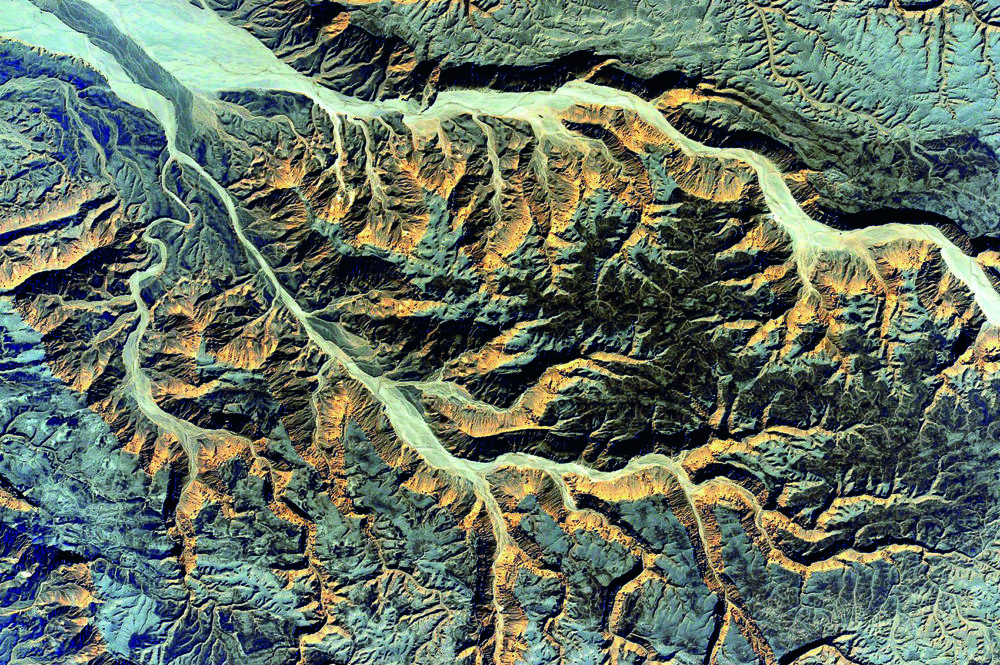

Kelly took hundreds of photographs while he was in space, many of which he shares in his new book "Infinite Wonder: An Astronaut's Photographs from a Year in Space."

"Photography is a big part of the job, we get a lot of training in it," Kelly tells Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson. "But it really wasn't until I was living on the space station for long periods of time that I developed not only a little bit of a skill for it, but also a love for taking pictures — particularly pictures that have some artistic value to them."

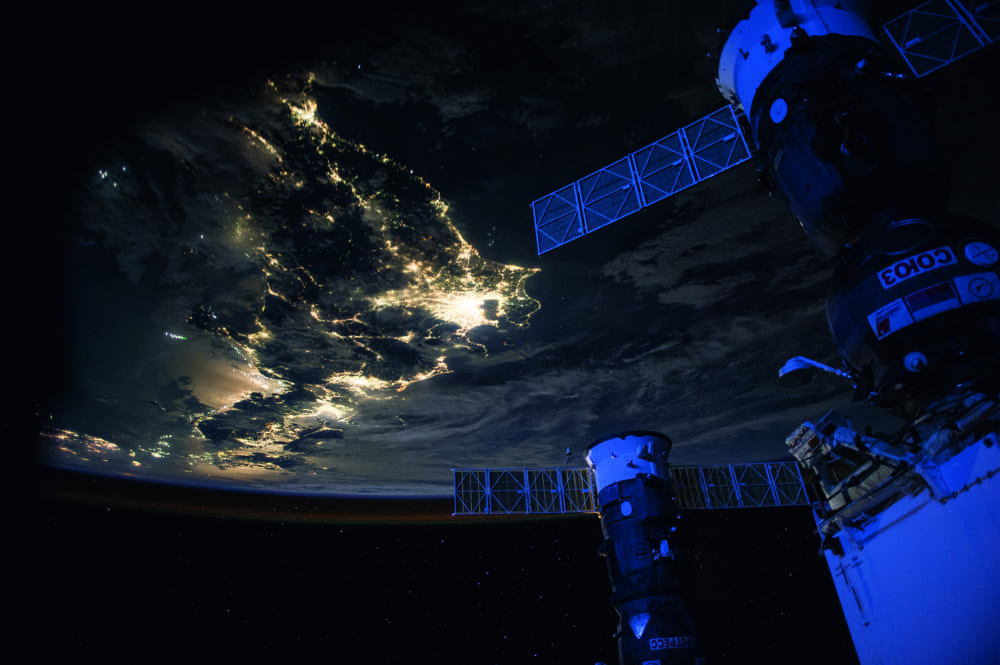

Speed was one challenge Kelly says he had to overcome to ensure Earth was ready for its close-up: The space station moves at around 17,500 miles per hour, or about 5 miles per second.

"It takes a while to develop a good technique — I think months, actually," he says. "Sometimes you get blurry pictures, but other times you get pictures ... that I think people find mesmerizing and interesting."

One of Kelly's favorite spots to shoot from space?

"The Bahamas is amazingly beautiful. It's the most expansive area of brilliantly blue water on our planet," he says. "I always enjoy getting pictures of the Bahamas — I enjoy visiting there, too, [it's] also a beautiful place up close."

Interview Highlights

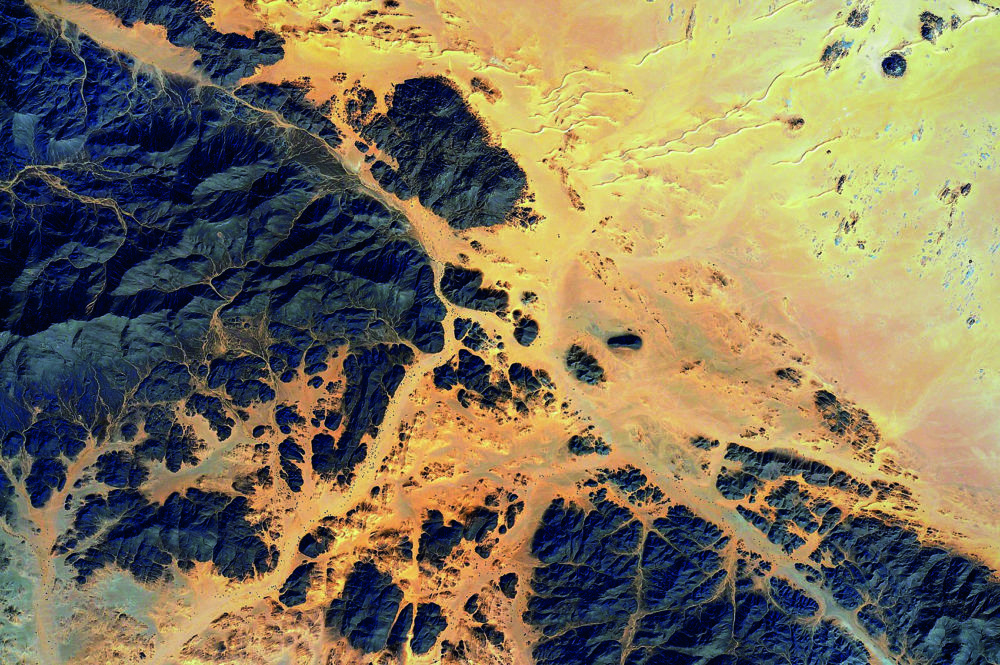

On the kinds of photos he took and the techniques involved in taking them

"The pictures that I became kind of known for a little bit were these pictures that we called 'Earth art,' so trying to make a wall-worthy image of planet Earth, using Earth as a subject matter. The way I would do that is I would use a really long lens, a telephoto lens, and choose interesting spots of the Earth. But we are going really fast: 17,500 miles an hour, which is 5 miles a second. You've got to move the camera really quickly and really steadily."

On the physical challenges that come along with being in space

"In the absence of gravity, the fluid in our bodies shifts, redistributes itself. So your head feels like it's full a little bit, or people often feel congested — big-headed astronaut is not just about our egos. It's also about the fact that your head swells up. It's not particularly comfortable. It never actually goes away, believe it or not. It gets better over time, but even at the end of a year, I still had a little bit [of a] swollen head.

"The carbon dioxide, when it's the lowest it can be on the space station, it's about 10 times what it is on Earth, 10 times higher, which is not comfortable. I think that also causes some congestion and eye irritation, when it gets really high I think it has a little bit of an effect on your ability to perform at a high level. It kind of gives you a little bit of a mental deficit, maybe.

"Our skin in space doesn't respond to that environment very well in a lot of people, so a lot of people get weird rashes and other things on different parts of their body."

On overcoming symptoms after his return from orbit

"I didn't feel well when I returned, after being in space for a year. I quickly got over the the worst symptoms, which was like stiffness and fatigue and swelling of my legs and nausea, and a little bit of dizziness. I got over those kind of things within a few weeks. But now, I don't have any symptoms of being in space for a year.

"I do have some structural changes in ... the physiology of my eyes, which is not completely uncommon for people that spend extended periods of time in space. I have some genetic changes: 7 percent of my gene expression had changed, actually more than that had changed in space, but when I came back, 7 percent, last I checked, still hadn't returned to normal. Gene expression is DNA, RNA proteins, those things that are very important to our physiology, and what makes a cell become a liver cell versus an eyeball cell had either turned itself on or turned itself off. We're trying to still understand — [we] don't know if it's a good thing or a bad thing. But I don't have any physical symptoms of that."

On the most difficult thing to deal with emotionally while spending hundreds of days aboard the space station

"It's being physically detached from your family, loved ones, friends, people in general. Even though I liked all the people I was in space with, [there was] not a whole lot of variety.

"The other thing that is I think challenging is just the fact that you can't go outside. You can't be in the sun, there's no rain, no wind. The environment within the space station never changes. You can't leave. It's not particularly a small place, I never really felt like I needed more room. But still it's a place that you can never get away from, and you're always at work when you wake up in the morning and when you go to sleep at night, you're still at your place of employment for a long period of time."

More Photos From The Book

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Jack Mitchell adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on November 5, 2018.