Advertisement

'Beethoven in Beijing' tells story of Philadelphia Orchestra's groundbreaking 1973 trip to China

This segment was rebroadcast on May 26, 2023. Click here for that audio.

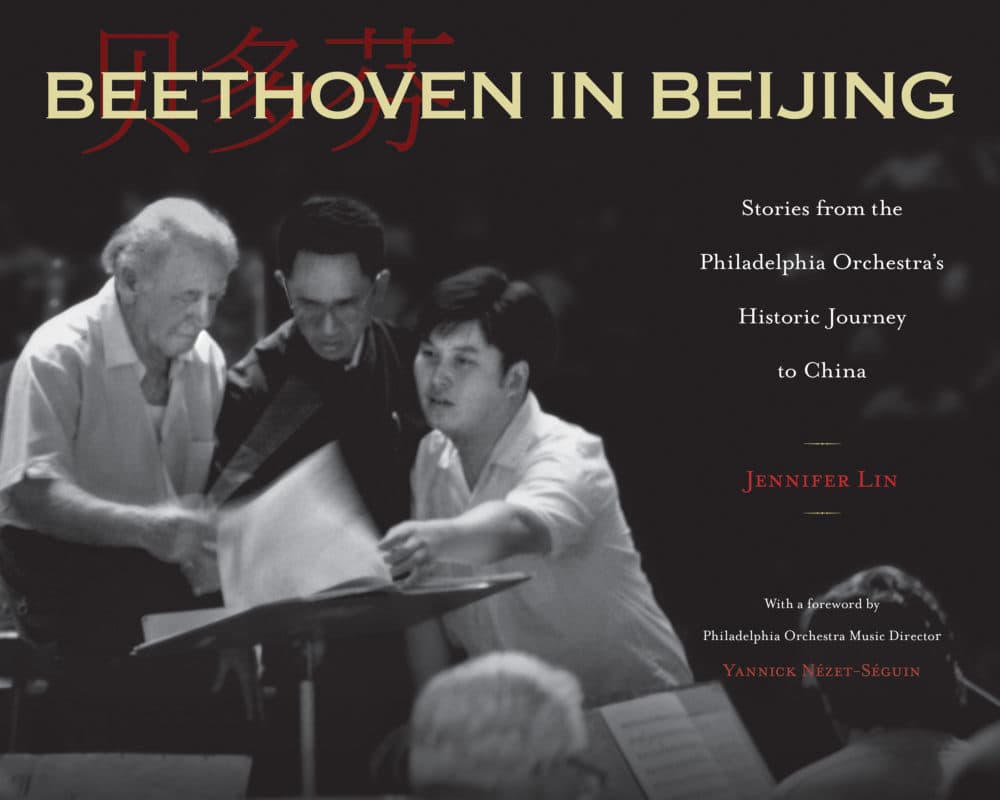

Author and filmmaker Jennifer Lin joins Here & Now's Scott Tong to discuss her book "Beethoven in Beijing," about how musical worlds opened when the orchestra went to China at a time when western music was banned there.

Book excerpt: 'Beethoven in Beijing'

By Jennifer Lin

Chapter 7

September 12: Red Carpet Welcome

In the late afternoon, the Pan Am charter approached the airport in Shanghai in heavy fog and rain. Nicholas Platt, the U.S. foreign service officer stationed in Beijing whose job was organizing tour details and escorting Ormandy in China, flew to Shanghai to meet the plane and relay news sure to upset Ormandy.

Daniel Webster: No one had a hint of what awaited them in China. Feicheng (Mandarin for Philadelphia) was coming. The plane came in low over tilled fields and rolled to a small terminal.

Eugene Ormandy: There was mystery all over the plane. Everybody came to me, and said, “What do you expect?” I said, “I don’t know.” At one point, one of my colleagues screamed “I see land!” China. The mainland. We were all excited.

Herb Light, violin: This was unknown territory to the pilot. And I’ll never forget, there was rather a low ceiling when we came into Shanghai, and they were going back and forth. And afterwards, the pilot told us when we finally got in safely, “Never been here before. Just wanted to make sure.”

Advertisement

Ormandy: We didn’t know what we were going to face until the door opened in Shanghai where we had to stop first. I was asked to be the first one to go off the plane and my wife to follow me. There was a red carpet out and on both sides of the carpet, there were a number of people. On the left side was the diplomatic corps; on the right, the musicians of the local symphony orchestra, all applauding us. They were just as warm and wonderful as could be. We only spent an hour and half at the airport until they filled gasoline into our plane.

Nicholas Platt: I had left for Shanghai to meet the orchestra’s plane and fly with them to Beijing. I had hoped to be able to get together with the Ministry of Culture officials handling the visit from the Chinese side. But I was held at arm’s length until twenty-five minutes before the orchestra landed. That was when Mr. Situ [Huacheng], the glum but competent concertmaster of the Central Philharmonic Society, entered the VIP lounge where I was waiting. He sat down and told me with deep apologies that certain revisions in the programs would be required. The biggest issue was performing Beethoven's Sixth Symphony. It had been discussed throughout the negotiations leading up to Ormandy's arrival. The Chinese desire to include it—and Ormandy's negative attitude about it—were known, but left unresolved until now. I dreaded raising it with an exhausted eminence I had never met.

Sheila Platt: Because the rules kept being changed, Nick had to give Ormandy bad or complicated news every step of the way. And Ormandy arrived sort of with his lip stuck out about all the things he wasn’t going to do.

Platt: The leadership now wanted concerts that packaged Beethoven’s Sixth, an American composition, and the Yellow River Concerto. I told Situ I would do my best to work the changes, but feared the consequences of confronting Ormandy with major issues after more than 20 hours of grueling travel.

John Krell: The airport was almost deserted and had an eerie frontier atmosphere. Mao caps and buttons began to appear and my friend bought me a Chinese beer. Waitress refused our proffered token of two American coins even though my friend went through an elaborate charade to equate Lincoln and Washington to Chairman Mao.

Platt: We got on the plane for Beijing. The issue of Beethoven’s Sixth was crucial to the success of the visit. Confronting difficult topics is what diplomats are paid for. So I sat down next to Ormandy and plunged in. I told him, “Maestro, we have a request from the top levels of government to play Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony.” And he looked at me and he said, “You know I hate Beethoven’s Sixth. I didn’t bring the scores. I don’t want to play it.”

Light: Ormandy being Ormandy, nobody told him what to play, and he was furious.

Platt: I said, “Let me try to explain to you why they think Beethoven’s Sixth is so important.” And I just started making things up.

Light: Ormandy did not hate the Sixth. But I think Ormandy felt that the Sixth Symphony was not showing off the orchestra to his liking. That’s the only reason he rebelled against it.

Platt: I told him, first of all, the Chinese loved program music, music that represents scenes. Second of all, this is a government that came to power on the backs of a peasant revolution and pastoral symphonies are all about peasants and farming life. And in the fourth movement, a big storm comes up and, of course, they think that’s the revolution. Then, there is a very peaceful, quiet ending, which they regard as the triumph of the Communist Party. Ormandy looks at me and he rolls his eyes

Light: I think he was convinced by Nick Platt that Chinese-American relations were at stake here unless he decided to give in.

Platt: Ormandy sighed and said, “If that’s what they want, that’s what they shall have. I am in Rome and will do as the Romans. I will forget my own rules.” I almost collapsed with relief. I told Sokoloff about our conversation and advised him to keep Ormandy’s willingness to play the Sixth in his back pocket during the protracted negotiations that were bound to follow.

From Beethoven in Beijing, by Jennifer Lin. Copyright © 2022 Temple University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or printed without permission in writing from the publisher.

This segment aired on May 27, 2022.