Advertisement

Reporter's Notebook

Why Bobby Guarente May Be The Key In Learning Who Pulled Off The Gardner Heist

In 2010, FBI agent Geoff Kelly and the Gardner Museum security chief Anthony Amore were high-fiving one another. They felt they had just made a breakthrough in the Gardner Museum heist case.

Elene Guarente, Bobby Guarente's widow, told them that six years earlier, her mob-associated husband handed over several of the museum's stolen masterpieces to his best friend in a seafood restaurant parking lot in Portland, Maine.

Her tip may not have led to a recovery, but her information was central to the reason top federal officials called a press conference in 2013. It was the first time authorities spoke so publicly about the case, so it raised public hopes that a recovery might soon be at hand.

Yet none of the federal officials who spoke at the press conference knew about another member of Guarente's family who reached out to authorities with information.

Shortly after Guarente’s death in 2004, his daughter and his good friend from Maine, retained a lawyer who approached the museum with proof that they could facilitate return of masterpieces.

On two occasions, Guarente’s daughter Jeanine, accompanied by Earle Berghman, submitted shreds of fibers that Jeanine contended came from the paintings that her father had stored in their home in Madison, Maine. Tests ordered by the museum showed on both occasions that the submitted material had not come from the stolen art pieces. Jeanine, now 49, has declined to be interviewed about her efforts to try to convince the museum that she had access to the stolen paintings.

However, Berghman, in an interview in 2014, told me that while Guarente never told him he had the paintings, he gleaned in separate conversations with Jeanine and Elene that Guarente had wound up with the stolen artwork and had stashed them away.

Maine law enforcement records attest to the close relationship Berghman had with Guarente, but Berghman says he has yet to be interviewed by the FBI about his ties to the Boston gangster and his family. The FBI has declined to speak about Berghman and his claims.

However, Bernard Grossberg, a Boston attorney, and Gardner trustee Arnold Hiatt confirmed Berghman’s account that he had accompanied Jeanine Guarente twice in 2005 to Boston with shreds of material that Jeanine contended had come from stolen Gardner paintings. Tests done on the first shreds showed they were actually chips of house paint. Tests on the second pieces submitted showed they had come from the covers of magazines, according to Grossberg and Hiatt.

“I was very hopeful about this when the chips came,” Grossberg said in 2014. “Unfortunately, testing proved them otherwise, so all those hopes evaporated.”

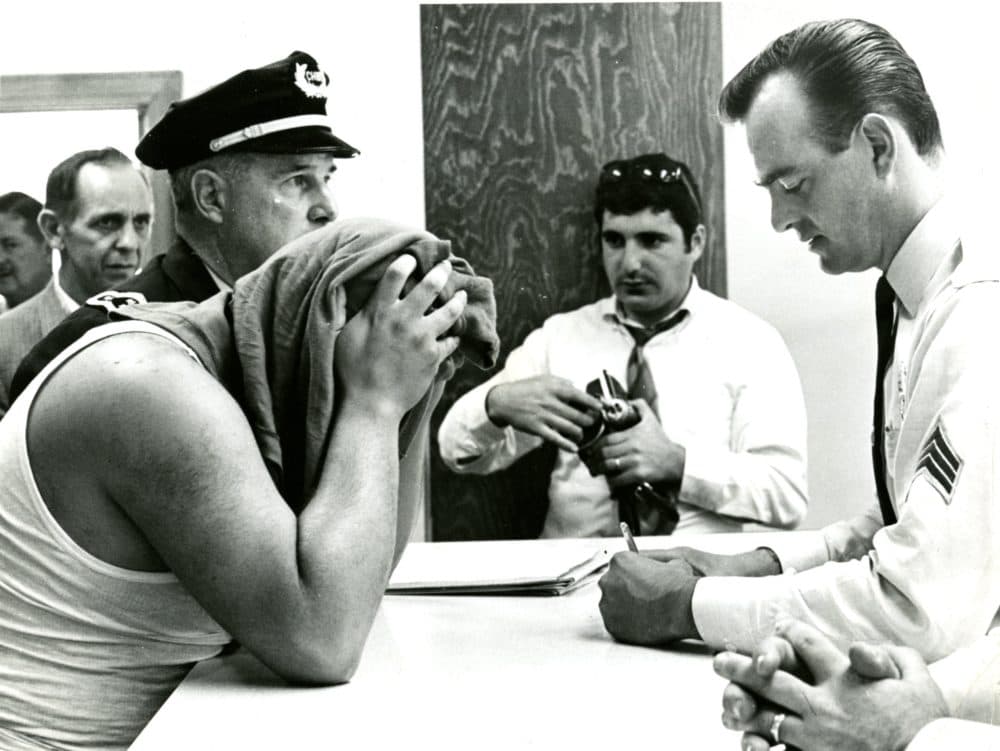

A Boston native and Marine veteran, Guarente’s name has been associated with several who knew the museum’s poor security made it vulnerable to a heist. People like Ralph Rossetti of East Boston who had surveilled the Gardner for a heist in the early 1980s.

After his release from prison on bank robbery charges in the 1980s, Guarente moved to a small town in central Maine where he would bring friends and family members for hunting and fishing trips. Among those he hosted was Robert Donati of Revere, and David Turner of Braintree, whose names have been associated for years with the Gardner theft. Guarente was also a close friend of Carmelo Merlino and seen often at Merlino’s auto repair shop in Dorchester, where the authorities once surmised that the Gardner theft was planned.

In a saga littered with con artists and dead ends, I have come to view Guarente as a legitimate suspect — and worthy of further investigation. Not only would he have been able to gain possession of the stolen artwork from several associates long tied to the heist, but his decades-long involvement with organized crime would also give him a way to hide the masterpieces.