Advertisement

Federal Authorities Are Still Arresting Immigrants Who Aren't Top Priorities For Deportation

Part 4 of a four-part New England News Collaborative series called "Facing Change"

In 2014, the Obama administration issued a federal memo aiming to put an end to random deportations of people living illegally in the U.S. who aren't criminals. But a closer look finds that there are still cases where immigration authorities are ignoring these policies, including in Vermont.

Before we look at some arrests of dairy workers in Vermont, here's some background on how and why federal policy changed.

Two years ago, the Obama administration ended a widely unpopular program called Secure Communities.

The program resulted in the indiscriminate deportation of people in the U.S. illegally who were contributing, taxpaying members of their community but had had a minor run-in with the law — something as simple as running a stop sign.

Nationally, the program created such rampant distrust of police among community members that many mayors and a few governors announced they would not cooperate with the federal requirements.

So in 2014, the Department of Homeland Security replaced Secure Communities with guidelines to prioritize for deportation people who are "threats to national security and public safety."

"ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] had strict guidelines: You're only supposed to be going after criminals," says Enrique Mesa, an immigration attorney based in Manchester, New Hampshire.

And the other part of the problem, Mesa says, is that in many cases local law enforcement is alerting immigration authorities whenever they encounter someone they suspect is here illegally.

Advertisement

"In Vermont, that I have seen, is that if you are picked up for driving without license or DUI, the prosecutors or the police will notify ICE," says Mesa.

A DUI is a deportable offense — but it's considered a second-level priority, which falls below a slew of high-priority crimes including terrorist acts, espionage and aggravated felonies.

"Unfortunately ... I've been seeing in my neck of the woods, in New Hampshire, that even for simple driving without license, ICE is just picking people up and just detaining them, left and right," Mesa says.

For example, take the story of Victor Diaz, a dairy worker in central Vermont (who, to be clear, is not Mesa's client).

Diaz, 25, has worked on an Addison County dairy farm for nearly three years. He is one of seven workers from Mexico or Guatemala who keep the 950-cow farm running 24 hours a day.

On a recent blustery afternoon, he took me into the employee living quarters. We talked in a sparse kitchen, just upstairs from the milking parlor. The stairwell was filled with the acrid smell of manure, combined with the sweet warm scent of fresh milk.

Diaz works the 12-hour night shift. "I come in to work at 7:30 p.m. and leave at around 1:30 a.m.; and I come back in at 3:30 a.m. until around 10 a.m.," he says. "In the middle of the night I have about two hours to eat something, sleep for an hour, and then go back to work."

Last year, Diaz was pulled over by police and charged with driving under the influence. At the time, he had a driver’s privilege card, a legal document that both Vermont and Connecticut offer to people that requires proof of residency, but not proof of citizenship.

Diaz pled “no contest” in court, and paid a $400 fine.

He wouldn't say publicly whether he understood that his plea could make him a priority for deportation.

Yet five months later, in April 2016, Diaz was in Stowe with friends at Mexican cultural event when he was approached by two agents wearing civilian clothing.

"They asked me if I was José. My name is José Victor, and I’m used to people calling me Victor so it seemed strange they would call me José," he says. "And I said, 'Yes, I am.' [They then said,] 'Well, we are ICE agents, we are here to arrest you.' And then he said to give him my hands and he handcuffed me and took me to his car."

It's unclear exactly how ICE learned about the DUI. Representatives from ICE declined to comment for this story.

But there are two likely ways ICE could have tracked Diaz down.

First, when someone is booked by local or state police, his or her fingerprints are submitted to a database run by the FBI, and immigration authorities have access to that info. This practice began under the Secure Communities program and is continuing under the new federal guidelines, or Priority Enforcement Program.

Second, it is possible that local law enforcement or prosecutors alerted ICE that they pulled over someone who might be in the country illegally.

That opens the door to racial profiling, says James Duff Lyall, the executive director of the Vermont chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

"Vermont has policy on the books that limits, explicitly limits, local law enforcement from participating in immigration enforcement," Duff Lyall says. "And yet we are seeing examples of local law enforcement inserting themselves into immigration enforcement, in disregard of Vermont state law, and also raising serious constitutional and civil rights concerns."

Vermont has laws specifically limiting local law enforcement from acting as immigration enforcement, including the fair and impartial policing policy.

Not only are police not supposed to be playing the role of immigration officials, but Duff says there are also concerns that immigration officials are not always adhering to the new federal guidelines.

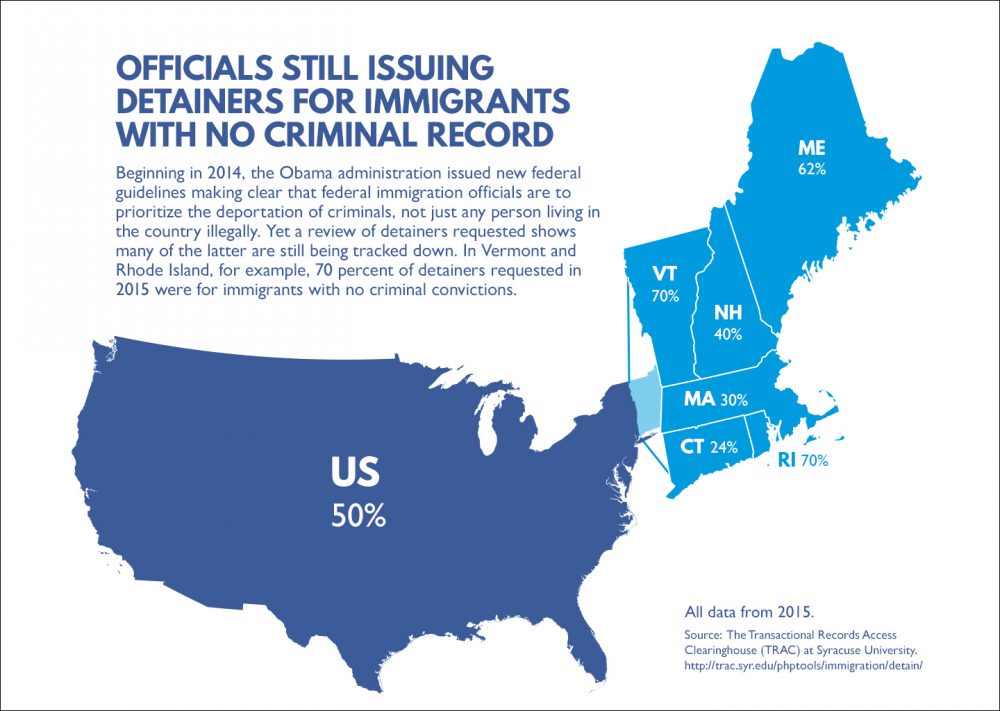

In fact, in New England, anywhere from a third to half of people for whom ICE issues detainers — a request to local police to hold that person — have no criminal record and have not been arrested before.

Miguel Alcudia is one example. He works on the same Vermont dairy farm as Diaz, and he was picked up by ICE earlier this year on the grounds that he's living in the country on an expired visa.

"It was a Thursday and I was on my way to the bank to cash my check, but I was detained before I got there. ICE arrested me," says Alcudia.

"But I don't know why, because I'm not a priority to be deported," Alcudia adds. "I'm not a criminal. I came to this country just to work."

Alcudia says when he asked the immigration officials why they picked him up, "they admitted that someone had called them about me. The ICE officer who detained me said he had gotten a call from someone who told them about me."

Both Alcudia and Diaz are also activists with Migrant Justice, a Vermont group that advocates for farm worker rights. Both were released on bail after multiple letters of support from the community, and from Sen. Bernie Sanders.

The two are awaiting their deportation hearing in front of a judge in the coming months.

In other cases, local police are stepping outside their authority. Take the case of Lorenzo Alcudia; he's Miguel's cousin, and also a Mexican national who was working on a Vermont dairy farm.

He was a passenger in a car where the white driver was pulled over for speeding in Grand Isle County. After deciding not to give the driver a ticket, the deputy sheriff detained the car for an hour while he called border patrol.

This detention occurred despite the deputy sheriff finding no sufficient evidence of criminal activity, according to a report by the Vermont Human Right’s Commission. The report concluded Alcudia was detained because of the color of his skin and his limited English.

Border patrol confirmed that Alcudia does not have a criminal record, but came and picked him up anyway for residing in the country illegally.

Alcudia's lawyer, Robert Appel, says the federal courts are quite clear this kind of roadside detention without any reasonable suspicion of criminal activity is illegal.

"Detaining an operator and a passenger and the vehicle is all seizure under the Fourth Amendment. And therefore in my view, the extended detention was unconstitutional as well as racially discriminatory,” Appel said this summer after the ruling came down.

The Grand Isle County Sheriff Department paid nearly $30,000 to settle the discrimination instance, but that doesn't change things for Alcudia.

He is still awaiting deportation proceedings.

Like Victor Diaz and Miguel Alcudia, his fate rests on the immigration judge's discretion — and the judge's interpretation of the ever-changing immigration policies.

This segment aired on December 22, 2016.