Advertisement

'Phil Spector' Sings An Unchained Malady On HBO

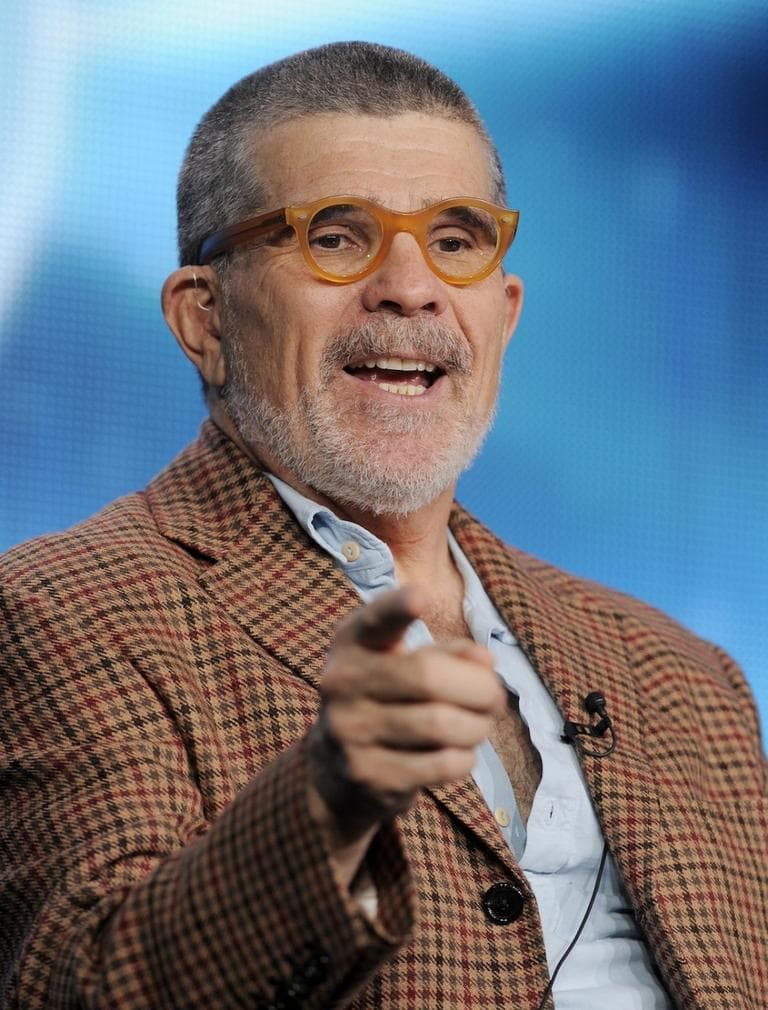

This has been the year of the playwright-screenwriter. There’s nothing new in playwrights earning extra dough and recognition on that score, but this year four of the biggest and most respected names in the theater all left the stage behind for “Lincoln” (Tony Kushner), “Seven Psychopaths” (Martin McDonagh), “Parade’s End” (Tom Stoppard) and now “Phil Spector” (David Mamet).

Al Pacino walks a fine line of going too mega with Spector's megalomania, but he’s always, often amazingly, on the right side of that line. He's frightening and funny, often simultaneously and he’s larger than life without being quite seductive.

That’s evident in the enjoyable “Phil Spector,” his HBO movie, which debuted Sunday night and will be rebroadcast through the month, about the legal defense (headed by Helen Mirren) for Spector (Al Pacino, who else?) after he was accused of killing actress Lana Clarkson. I realize that the word “enjoyable” might seem kind of dodgy in a movie about a woman’s tragic death, but the truth is that Mamet isn’t dealing with the truth. A disclaimer at the top makes it clear that this is not supposed to be a docudrama but a work of fiction.

What, then, is the point? Mamet and executive producer Barry Levinson have indicated that they’re more interested in the relationship between Spector and his lawyer and in the mythological aspects of the story – Mirren as Linda Kenney Baden enters the Spector household like Beauty in "Beauty and the Beast," convinced that he is indeed the beast who killed an innocent woman.

She never thinks of him as the handsome prince, but she does eventually believe the defense line that had Spector pulled the trigger – Clarkson was shot in the mouth – he and his white suit would have been blood-splattered. It’s a matter of public record at this point that the film doesn’t think that its mission is to come to any conclusion about what happened.

Nevertheless, the vilification of a potentially innocent man ties in with Mamet’s concerns over the years with that subject –- his play, “Oleanna,” for one and his film version of Terrence Rattigan’s “The Winslow Boy” for another. Mamet says he became interested in the subject matter after watching a documentary, “The Agony and Ecstasy of Phil Spector,” which cast some doubt on his guilt.You could also speculate that Mamet identifies with Spector the gun enthusiast and Spector the artist whom the press dismisses as a has-been. (Hey, if Mamet is free to speculate about Spector then I’m free to speculate about Mamet.)

I'm making this sound much more humorless than it is. Mamet and his old pal, Pacino, do a terrific job with Spector. Both these guys can go over the top (“Scarface,” anybody? “Godfather III?”). You get the sense, though, that television enforces a certain discipline on the writer and actor. There are flashes of Mametspeak –- repetitive bursts of dialogue, often with four-letter punctuation –- but its not overwhelming. Pacino, as in his definitive portrayal of Roy Cohn in HBO’s “Angels,” walks a fine line of going too mega with Spector's megalomania, but he’s always, often amazingly, on the right side of that line.

Advertisement

He's frightening and funny, often simultaneously and he’s larger than life without being quite seductive. His overbite is a bit exaggerated, but also indicates that there’s something a little off. His Spector has convinced himself of his greatness and his innocence, and seemingly his lawyer as well, but Mamet is smart enough not to get sucked in. There’s a benefit of the doubt to both sides of the story.

Here's a sample. Contains strong language:

As a director, Mamet has always believed in not going auteur on the proceedings, both in movies and on stage. That doesn’t prevent the movie from having a strong visual sense. We build our own beautiful cages, whether mansions or legal offices. It won’t surprise anyone that Mirren delivers a superb performance and in her own understated way stands toe to toe with Pacino.

Mamet also doesn't believe in actors being at all introspective about their work; he thinks they should deliver their lines like soldiers going into battle. Interestingly, that approach works particularly well with the closing song. After threading original Spector songs like "Unchained Melody" and "He's a Rebel" throughout the film, the closing credits go out with Rebecca Pidgeon's lovely, unaffected "Spanish Harlem." (She also has a secondary role in the film.)

In the end, I don’t think that Mamet comes up with anything all that provocative to say. In the battle of the HBO playwrights Stoppard’s work on “Parade’s End” is the far more thoughtful work. As Mamet’s essays show, whether as a liberal or a conservative, he’s not a great thinker.

But he is a talented writer and filmmaker. Who knows, maybe Mamet the playwright even has another outstanding play or two in him, but for the moment it’s rewarding enough to watch him have fun with Pacino on HBO.

This program aired on March 22, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.