Advertisement

Barry McGee Tags The ICA

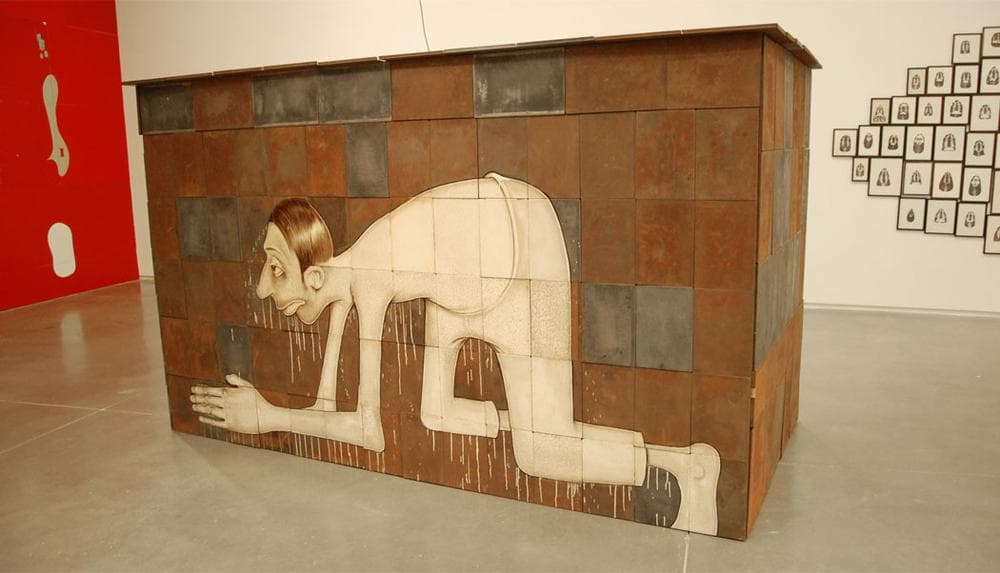

A rusty shed stands in the third gallery of the thrilling Barry McGee exhibit at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. The exterior is plated, or armored, with old rusty metal trays that were once used for letterpress printing. And one side is painted with a larger-than-life, brown and white cartoon of a sad-eyed man, unshaven and wearing no shirt or shoes. He’s on his hands and knees in exhaustion and defeat, with his hands together perhaps praying. It could be a self-portrait.

A rope blocks us from going in the doorway. But on the walls inside are small groupings of folksy drawings and paintings of ladies and trees and shoes by Margaret Kilgallen, whom McGee met in 1990 and married in 1999. The atmosphere in there is sweet and jaunty, because that’s the tone of much of Kilgallen’s work.

She died in 2001 at age 33, just weeks after the birth of their daughter, Asha. Kilgallen had been diagnosed with breast cancer, but had declined to get treatment during her pregnancy so as to protect her baby. It killed her.

The museum’s wall text makes no mention of the family story, but if you know it, goodness, the shed stops you cold. It feels like both a tomb and a shrine to the Kilgallen, to the incredible sacrifice she made, to the terrible loss McGee and his newborn daughter suffered.

“Barry McGee,” which was organized by the University of California’s Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive and is on view at the ICA through Sept. 2, is a full-on retrospective of the artist, who along with Kilgallen, Chris Johanson, Alicia McCarthy and others pioneered the folksy, hand-made Mission School style that emerged from the Bay Area in the 1990s.

McGee was born in San Francisco to an Irish-American auto body repairman and a Chinese-American secretary in 1966. He grew up with his mother, brother and two sisters in the suburb of South San Francisco after his parents divorced. In 1984, at the relatively late age of 18, he got into graffiti.

“Zotz was the one who handed me the spray can. He’s the first person that said, ‘Barry, lets go... it’s time to catch tags,’” he recalled in the magazine “Swindle.” His street name “Twist” was inspired by the title of a motor scooter zine.

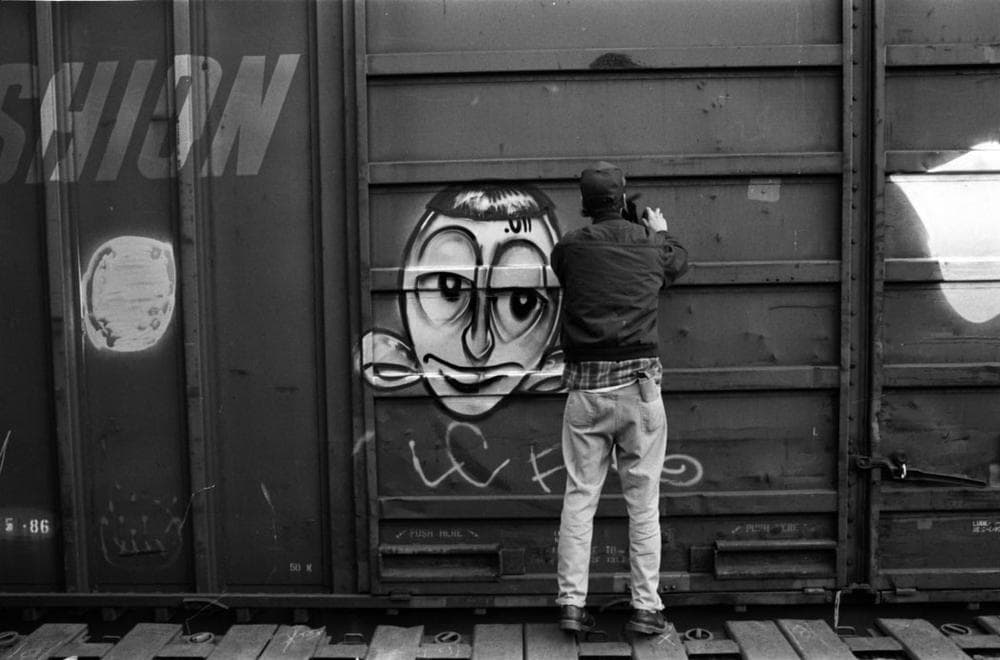

Studying at San Francisco Art Institute, from which he would graduate in 1991, he became friends with a fellow student from Cambridge, Massachusetts, who tagged under the name SR.ONE. From him, McGee became familiarized with New York graffiti styles. McGee’s own loose, swaggering handstyle plus his giant two-tone sad-sack faces came to define graffiti in the Bay Area.

The ICA’s first galleries evoke McGee’s street graffiti with relics like spray cans, wire cutters, and a coat with secret pockets sewed into the lining to hide spraypaint. A hand-pained sign, apparently stolen (but perhaps a copy) reads: “To all taggers. Please do not mark this truck and do not remove this sign. Thank you.”

“Work done illegally outdoors or without permission feels like pure freedom to me,” McGee told Artinfo.com in 2012. “I understand how it can upset many in our society, but in the bigger picture it is ultimately about freedom. We are living in a time where public space has become a commodity for corporations to control and dictate what is seen and heard.”

A red wall half the width of the museum is painted with McGee’s signature sad gray faces and black and white graffiti. Further evoking the streets, some of it painted over with gray blobs as if by some clean-up crew. A strangely tall, skinny robot mannequin depicts McGee’s longtime collaborator Josh Lazcano in a hoodie perching on his tiptoes atop a trash can tagging “Amaze” on the wall. It’s a sort of goofball monument to the surreptitious graffiti life.

“I have been fascinated for some time, how the general public is often left in the dark, in some of the situations the tagger puts him/herself through,” McGee told “Black and White” in 2008. “I’ve had many, wonderful experiences as a youth, perched upon a friend’s shoulder, and another above me, spray painting, just to eek out some kind of existence on this planet. It always represented a team effort, working together on a common goal, slight rebellion, and standing back and still wondering how we did that.”

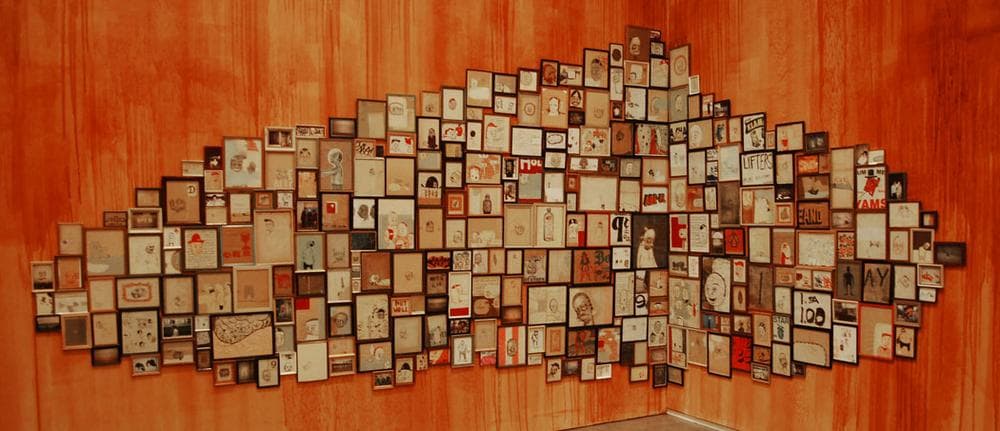

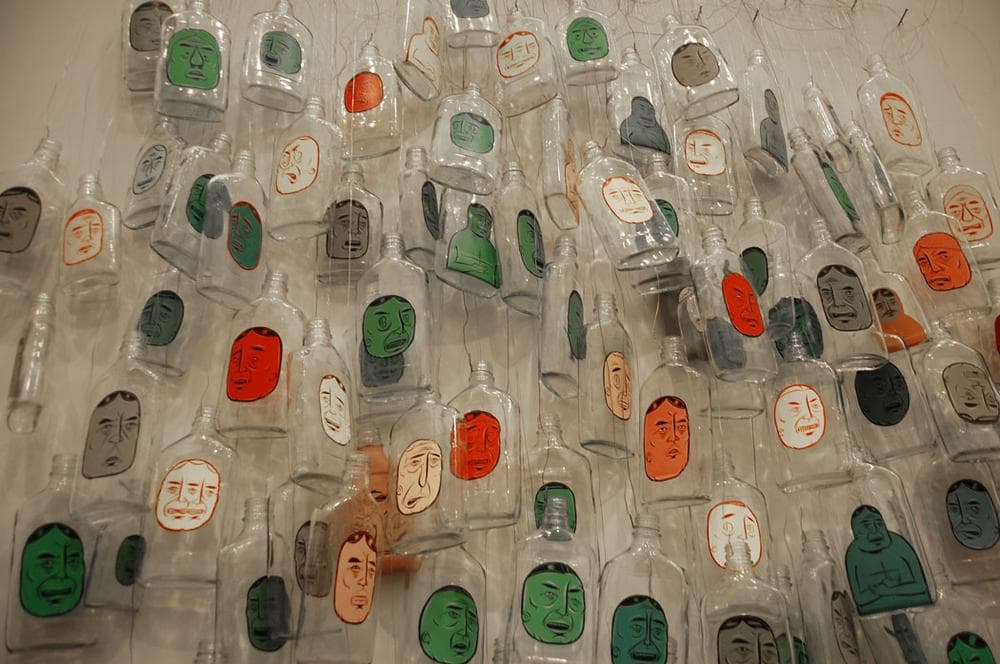

Traveling to Brazil for an eight-month residency in 1993, McGee met the Os Gêmeos graffiti twins, introducing them to his two-toned character style, which they would adapt to create their signature style (featured in their mural last summer in Boston’s Dewey Square). He returned home inspired by dense displays of ex-votos (offerings) at a Catholic church in São Cristóvão. Starting with an exhibition the following year, he began similarly filling gallery walls with sizzling clusters of framed drawings or empty booze bottles (some of which it’s said he bought from homeless folks) painted with hangdog cartoon faces.

Even as the Bay Area’s dot-com economy boomed in the 1990s, McGee’s art was shot through with a down-and-out sadness, with the difficulty and pain of getting by. He’s described his sad-sack characters as everymen or San Francisco’s homeless. After a while, though, you start to feel like if you’ve seen one of these cartoons, you’ve seen them all.

McGee’s metal shed/shrine is the turning point of the show. After Kilgallen’s death, you might expect his work to turn darker. But after his early rusty depression, his art suddenly lights up with eye-popping geometric Day-Glo abstract patterns, a ceiling-high tower of old televisions flickering with psychedelic imagery, and raucous urban funhouses.

“I’m more up beat now,” McGee told WhatYouWrite.com in 2009. “When I was younger I was more world-weary. I guess it’s a part of getting older.”

He’d already begun moving in this direction in 2000. Working with graffiti pals Steve Powers (Espo) and Todd James (Reas), McGee began filling galleries with life-sized urban bodegas, liquor stores, car service headquarters, check cashing outlets, and pileups of overturned vans and trucks. They were gritty Disneyland recreations of the scrappy fertility of the bottom of the urban economy.

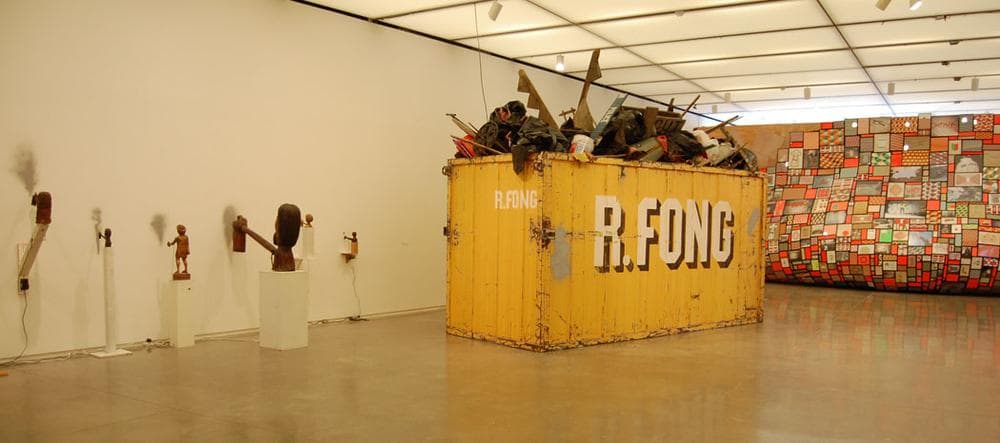

At the ICA, a row of wooden sculptures—folksy figures, African busts, cigar store Indians—are squeakily automated to wave wooden arms as if spraypainting the wall. Nearby a beat up, yellow shipping container labeled “R. Fong” is piled high with trash like a dumpster. The far end is open to reveal a bathroom inside and another animatronic Lazcano in a hoodie spraying “Amaze*” on the mirror under flickering fluorescent lights.

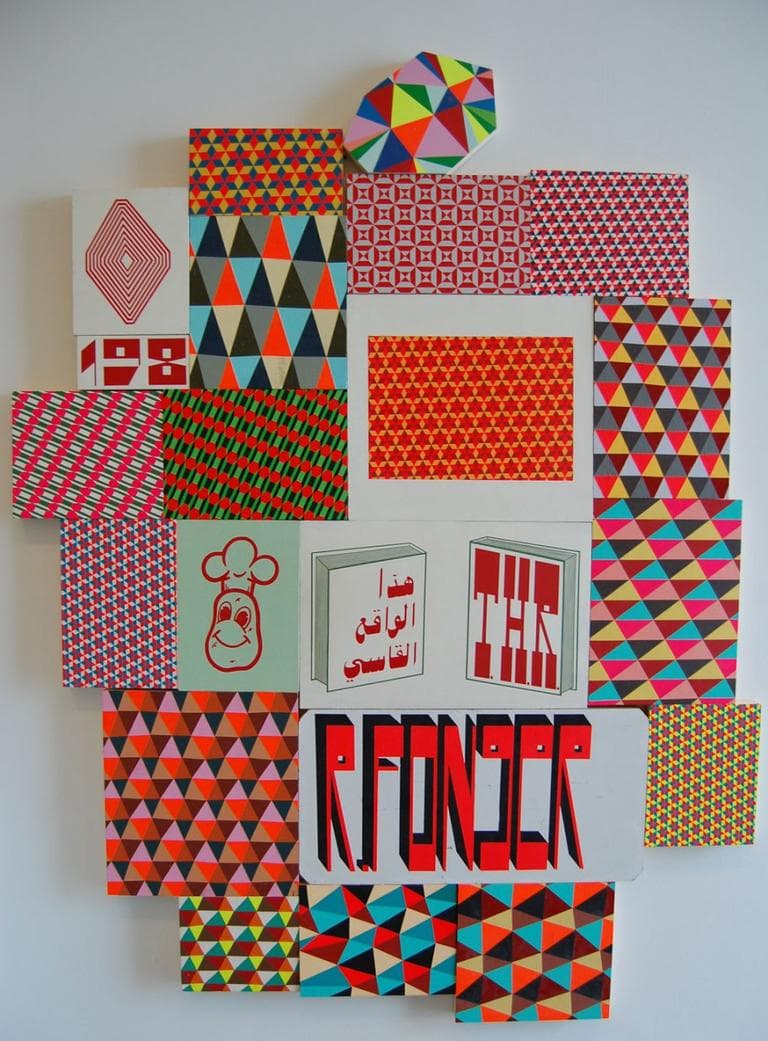

Across the room, a gallery wall is filled with paintings of geometric patterns, cartoon potato mascots, prices, and signs with old timey hand-lettering reading “THR,” DFW,” and “Fong.” Some of the signs reference art and graffiti crews McGee has been associated with—The Human Race and Down For Whatever. “Fong” refers to “Lydia and Ray Fong,” which McGee has occasionally identified as pseudonyms for him and his current wife Clare Rojas.

“Lydia and Ray Fong are more abstract, less associated with this popular trend of ‘street art,’ which is currently clogging the galleries,” McGee told Clark Magazine in 2009.

The final gallery looks both forward and back. Here are his latest geometric patterned abstract paintings and lists of numbers. But he also stocks this part serious, part satirical “contemporary art centre” with surfboards, 1980s skateboard decks, zines, sketches, a 1990 copy of “The Boston Tab” warning of a “graffiti plague” in the Back Bay, and photos of 1980s Boston and Cambridge graffiti by RYZE and SR.ONE.

McGee resents how graffiti’s outlaw rawness has been cleaned up and commercialized as street art. It’s a view he’s long held. “Whenever money becomes involved it’s not graffiti in that sense anymore,” he told Slap skateboard magazine back in 1993.

The gloomy view of his early work surfaces here and there. An automated wooden bust in the last room repeatedly bangs its head against the wall. But these days McGee is a mainly a successful creature of museums and galleries and payday gigs designing shoes for Adidas or advertising for Nike.

“I am a 42-year-old man, married, child. It has been a good five or six years since I’ve done a good rooftop or bold location,” McGee told "Black and White" in 2008. “What graffiti I do now, if any at all, is limited to, but not exclusive to, bathrooms, an abandoned car, and gallery walls before covering them with abstract panels. All of these locations hardly constitute a hardcore graffiti lifestyle, and definitely not in the eyes of a 17-year-old anymore.”

Previously: Don’t Call Barry McGee A Street Artist.

This article was originally published on April 08, 2013.

This program aired on April 8, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.