Advertisement

Can This Town Find A Home For New Boston Architecture?

The new book “Archive: Design Biennial Boston,” published by the folks behind Boston’s pinkcomma design gallery, is a showcase of new architecture from Massachusetts. But it’s also something more.

Like the gallery—which “aims to foster and recognize a more creative and experimental scene that has grown out of one of the world’s most significant capitals of architectural education”—the book is a lever to pry open opportunities in this often hidebound city for young Boston architects.

“It’s both an advertisement and a call to arms,” says Chris Grimley, one of the principals of the Boston architectural firm over,under, which also hosts pinkcomma, where he is a co-curator with his “Archive” co-editors Michael Kubo and Mark Pasnik.

“Boston’s on the cusp of a very interesting moment in its history with the mayor’s race and the amount of building,” Grimley says.

“Look at the amount of buildings going up,” he continues. “It’s all three or four large corporate firms that are doing it. … There’s no real voice out there saying there are other people out there.”

“Archive” is basically a sign saying look over here at all these cool, young(ish) architects around Greater Boston. Pinkcomma, which was founded in 2007, is the sharpest venue for examining new design in the city, filling a gap left by the disinterest of our major museums. “Archive” comes out of the gallery’s "Design Biennial Boston" between its founding in 2008 and the most recent edition, which was presented this spring at BSA (Boston Society of Architects) Space, where the pinkcomma folks were curators from February 2012 to this June.

“Archive” surveys 19 biennial winners—Massachusetts firms and individuals who are within 15 years of graduation from school. The firms are local, but their projects can be anywhere—though better than 50 percent of their commissions are for projects in the Bay State.

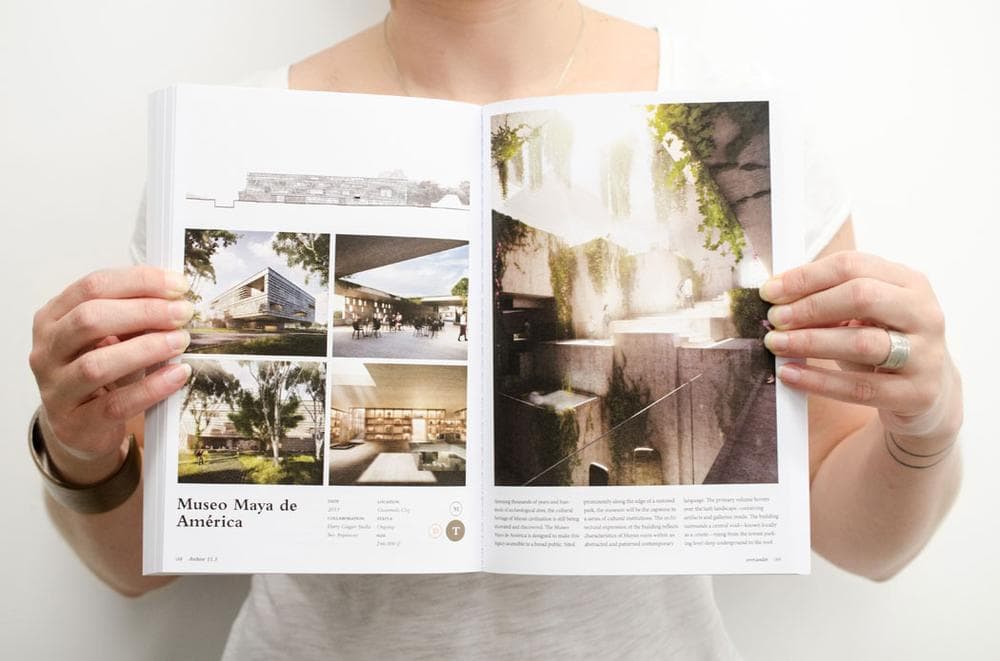

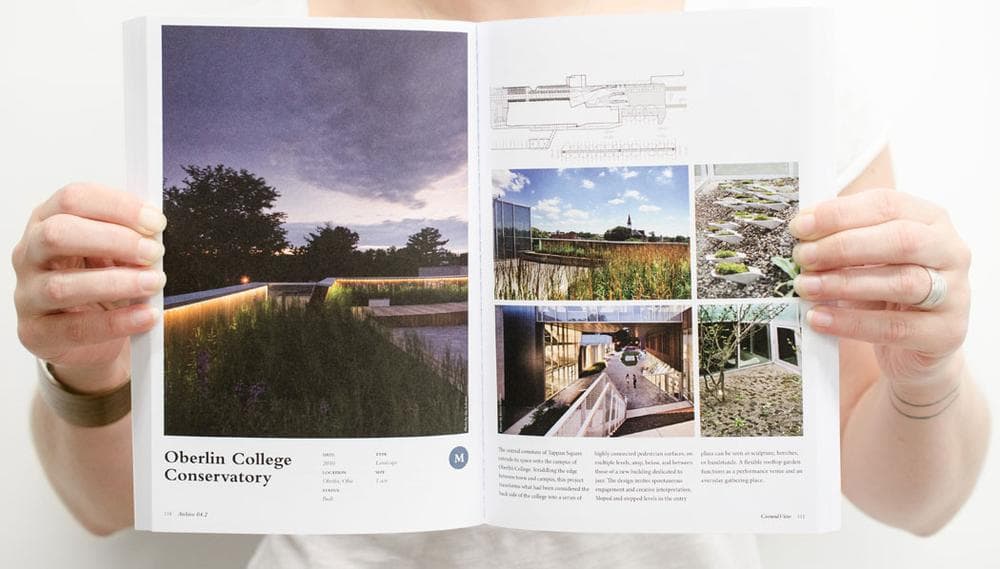

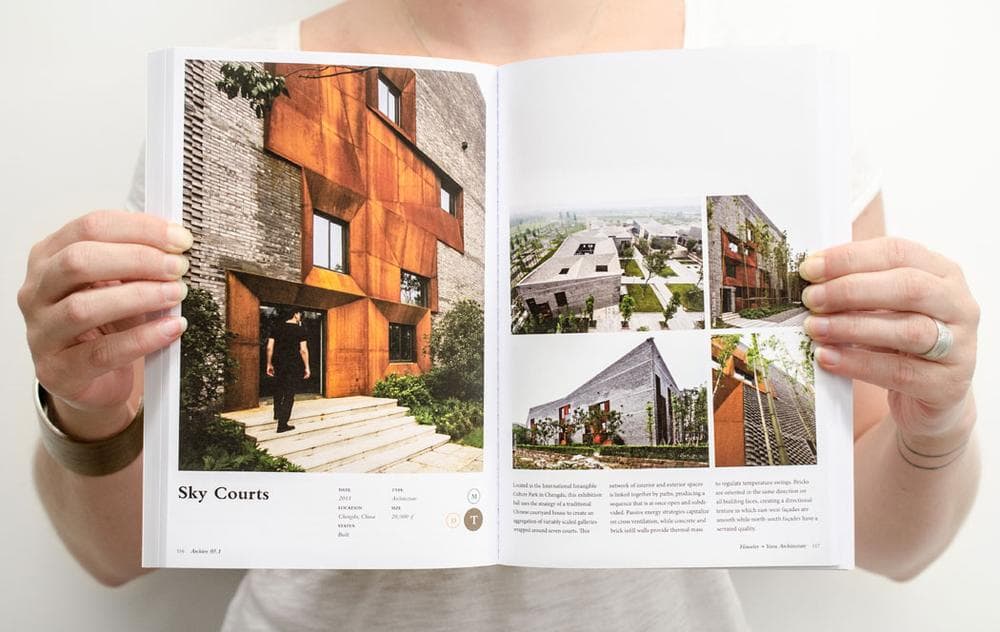

Featured projects include Dan Hisel Architect’s conversion of an abandoned New York railroad bridge into a guest house; William O’Brien Jr.’s sleek interior for Aesop Newbury Street; Höweler + Yoon’s bulky “Sky Courts” brick exhibition hall in Chengdu, China; GroundView’s minimalist Somerville playground and Oberlin College Conservatory garden; and over,under’s ongoing design for Museo Maya de America in Guatemala City. Many others haven’t been built—like C&MP’s 2010 proposal for a rooftop garden and community space atop a supermarket.

Advertisement

Is there a budding Boston architecture style?

“There’s this kind of belligerence that may have to do with the climate and the place. Pigheadedness. A survival mode. To keep operating in a city that’s been redefined as historic—since 1976—you need to be kind of bullish to get things built,” Grimley says.

“Any attempt to assemble this group of projects or practitioners into some kind of aesthetically cohesive narrative would be misguided and ultimately misleading,” warns Amanda Reeser Lawrence, co-founder of the architecture journal “Praxis” and a teacher at Northeastern University, in her essay “Localism” in “Archive.” “These 19 firms are connected not through a unified style but through their shared locality: teaching at the same schools, sitting on reviews, serving on juries. In essence, these practitioners research together in a metropolitan-scaled laboratory.”

“If anything, young Boston design might be defined by its roots in the academic world that we can’t avoid here,” Grimley agrees. “Eighty percent of people in these offices teach in some capacity.”

But he adds, “I don’t think there’s a real stylistic sensibility going on.”

However, if “Archive” is your guide to new local design, common approaches do emerge. The architects tend to favor straight lines and flat surfaces with few windows. They like industrial steel and concrete and fancy, little-processed wood, what’s often called “truth in materials.” The designs are sleek and Spartan, with little decoration. “There’s an efficiency and it might be because of budgets,” Grimley allows.

This Greater Boston-designed architecture is often geometry plopped on landscapes. It has a prefab feel and interest in aggregating lots of similar small units to create the big whole, sort of like pixels in digital photos. It feels like German Bauhaus by way of Harvard, or modernism after computers. It’s hard to say how much of this is a Massachusetts style and how much of this is just the local version of the international architectural zeitgeist.

The upshot, Grimley says, is “There’s plenty of talent here that could take over Fan Pier.” “Archive” suggests a Boston where much of what gets built here is, in Grimley’s words,” less “bland and corporate.”

“We that are staying here and trying to make a go of it,” Grimley says, “are vested in trying to tell the story that there is this generation of younger architects that are hopefully going to start working on these larger projects.”

What’s holding this back?

The problem isn’t just here, Grimley acknowledges. “It’s a typically American problem,” he says. But around Boston, “there are too many larger firms that eat up all the jobs,” he says. Building requests for proposals (RFPs) call for too much experience “and the developers want to go with tried and tested,” he adds.

Meanwhile the Great Recession has kept some young architects toiling in the offices of their elders, “waiting for the time when they might make the leap” to go out on their own, Grimley says.

So, he says, “a lot of people who get educated here, they just flee.” They see greener pastures in joining hip New York architecture firms or going home to Europe where “there’s more support [from governments] for younger firms to make a living.”

“You lose the sense of vibrancy that we can offer,” Grimley says. “There’s an energy to young design talent that’s different from the larger firms.”

This article was originally published on August 06, 2013.

This program aired on August 6, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.