Advertisement

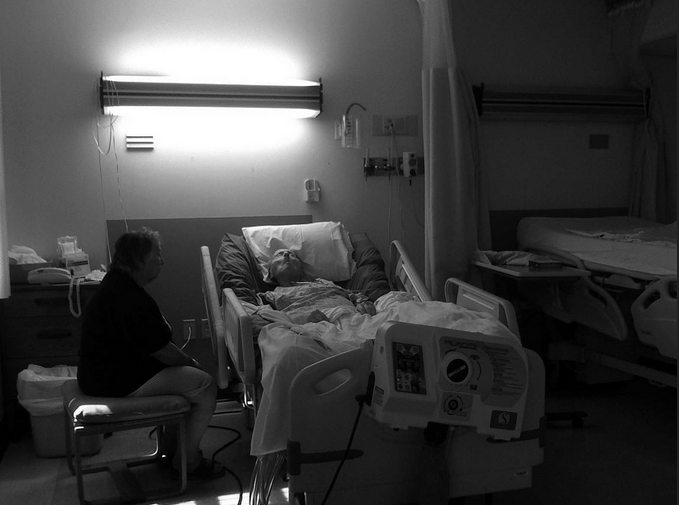

'Good Death' Still Eludes U.S. Health System Despite Decades Of Debate

By Richard Knox

Death is back in the news again. And it should be.

Death comes to us all. And in the U.S. at least, it's increasingly likely to be inhumane, institutional and full of misery. That's according to a growing body of evidence, including:

•A report last month from The National Institute of Medicine called "Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life." It’s a 500-page indictment of U.S. end-of-life care.

•A new book by Boston writer-surgeon Atul Gawande on the subject called "Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End."

•And recently, a must-read New York Times article — a powerful case study of how the American way of death has gone badly awry.

From these and other sources, one thing is clear: Too many Americans are still dying in hospitals and nursing homes; getting aggressive but futile care; and suffering more from the complications of treatment than from the pain of dying.

And with about 10,000 Baby Boomers turning 65 every day, it’s way past time to do something about it. “What is it going to take to ensure that patients in this country are receiving the right care at the right time in the right location, consistent with the right to choose?” Dr. Joan Teno wonders. “These are the things that keep me up at night.”

Teno, a Brown University faculty member, is among 21 authors of the recently issued Institute of Medicine report on dying in America.

Advertisement

The Forces Against Us

I called Teno after reading the IOM report (well, some of it) and, right on its heels, Nina Bernstein's detailed account in the Times about the last days of retired postal worker Joseph Andry and his daughter's struggle to honor his wish to die at home.

Despite her dogged efforts, she failed. The institutional forces arrayed against Andrey were too tenacious, the institutions’ incentives to maximize their reimbursement too powerful. At the same time, home health and hospice agencies have strong incentives to avoid “heavy needs” cases like his.

After Andrey died, just shy of his 92nd birthday, the funeral director told his daughter he’d never seen such deep pressure ulcers — a consequence of poor nursing care. By then he’d also suffered from antibiotic-resistant infections picked up in health care institutions. He sometimes lay for hours in his own excrement. He lost weight from poor nutrition (one nursing home stopped his protein supplements when his Medicare coverage ran out) and muscle atrophy (because nursing staff rarely got him out of bed).

The cost of Andrey’s end-of-life care added up to about a million taxpayer-provided dollars.

“It’s a touchstone case, an unbelievably sad case,” Teno says. But as her research amply documents, it’s all too typical.

For instance, last year Teno and her colleagues published a study of 848,000 deceased Medicare recipients showing that an increasing proportion are admitted to ICUs in their last month. In other words, more Americans are getting aggressive medical care at the end of life – the opposite of what many people, like Andrey, say they want.

The same study also documents an increase in the percentage of Americans experiencing what Teno calls “burdensome transitions” in their last days and weeks of life — transfers from hospital to nursing home and back again.

Teno and her colleagues also have found that dying patients who bounce around to different institutions are more than three times more likely to end up with a feeding tube, twice as likely to spend time in the ICU during the last month of life, and more than twice as likely to have a severe decubitus ulcer, or pressure sore.

It’s all frightfully expensive. Teno says Andrey would have been far better off if some of the $1 million it cost to keep him in hospitals and nursing homes had been devoted to home care, as he and his daughter wanted. But Medicare and Medicaid policy doesn’t support effective home care for dying patients.

Aggressive Care — But Futile

Over-aggressive care at the end of life is hardly a new issue. Nearly 20 years ago, a $29 million landmark study called SUPPORT found that half of doctors in five teaching hospitals didn’t know when patients preferred to avoid resuscitation when their heart stopped – a so-called Do Not Resuscitate order. It also found that nearly 40 percent of patients spent at least 10 days in an ICU prior to death, an indicator of aggressive but futile care.

The SUPPORT study failed to improve end-of-life care by having specially trained nurses inform doctors of patients’ poor prognoses and their preferences for less-aggressive care. But it did help spark a national debate about the way Americans die, and gave impetus to the hospice movement as an alternative to no-holds-barred end-of-life care.

But hospice care has fallen far short of what its advocates had hoped. Dr. Ken Covinsky, who participated in the SUPPORT project, notes that today most patients who get hospice care are enrolled less than two weeks before death – too short a time to have much impact on the kind of care they get.

And in August, Teno and her colleagues reported that nearly one in five hospice patients nationally are discharged from hospice programs alive.

Some of these patients improved unexpectedly, but Teno says many of them are dropped by hospice programs because their care became too expensive. For-profit hospice programs are especially likely to drop patients before death.

“The concern is that hospices could be discharging people to avoid expensive care, such as a CAT scan or an MRI, and that they are trying to game the system,” Teno told The Washington Post. “Some of the new hospice providers...may be more concerned with profit margins than compassionate care.”

The Same Conversations

Teno, a leader of the 1995 SUPPORT project, laments that “we’re having almost the same conversations about end-of-life care that we had two decades ago. Why can’t we do better?”

She doesn’t expect things to improve without major changes in the way doctors, hospitals, nursing homes and hospice programs are paid to care for dying patients.

Gawande, the Brigham surgeon and author, writes that sometimes even minor adjustments can greatly improve medical care:

Making small but key changes, like simplifying medications, controlling arthritis, ensuring good meals and maintaining social connections, can be more effective in prolonging life than some extreme medical measures.

Teno also thinks Americans need better information about the quality of care patients receive in hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies and hospice programs.

“When I book a hotel, I go to Trip Advisor and find out the best and the worst,” she says. “I want that same level of quality data for health care.”