Advertisement

Catching Cancer Early: Be Careful What You Screen For

True or false: It’s always better to catch cancer early.

Answer: False

But that absolutely doesn't mean we should give up screening for early detection of cancer.

Yes, it's confusing. But bear with me. Because two reports issued this week are a perfect illustration of why cancer screening is such a tricky topic.

Consider them both and you’ll have a better appreciation of the complexities of the issue. And why individuals and health policymakers need to think carefully about when to screen and what to do with the results.

One new report is about screening for thyroid cancer. It makes a strong case for why it’s not a good idea.

The other is about screening for cervical cancer. It’s an equally strong argument for why there’s not enough.

First, thyroid cancer screening. South Korea has gone in for it in a big way, as part of a national push for detecting all cancers for which there’s a screening test – cancer of the breast, uterine cervix, colon, stomach and liver.

The Korean program doesn’t include thyroid cancer in its screening program. But so many hospitals and doctors have ultrasound machines – which can detect tiny thyroid tumors with a quick neck scan – that thyroid cancer screening has become routine in recent years, for a fee of $50 or less. It’s an easy sell, and an easy way to make money.

As a result, South Korea’s rate of thyroid cancer has soared. It’s 15 times higher than it was in the early 1990s, before routine ultrasound screening. No other cancer is diagnosed more often there, which is pretty striking considering that thyroid cancer is the 10th most common malignancy in the U.S.

But curiously, deaths from thyroid cancer in South Korea haven’t gone down at all over the past two decades, according to an article in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine. And reducing cancer death is, after all, the reason for screening. The logic is that cancers will be more curable if they’re caught early.

Advertisement

The Korean story shows that’s not true for all cancers. Thyroid cancer is the epitome of a malignancy that it’s usually better not to find.

Dr. H. Gilbert Welch of Dartmouth and his Korean co-authors point out that autopsy studies dating back to 1947 show that many people have previously unsuspected thyroid malignancies at the time of death.

Researchers estimate that at least one in every three people has a thyroid malignancy, “the vast majority of which will not produce symptoms during a person’s lifetime,” Welch and his coworkers write.

Ultrasound scans reveal this enormous reservoir of mostly harmless thyroid cancers. Welch et al call it an epidemic of “over-diagnosis.” They point out that the thyroid cancers being diagnosed in South Korea are almost always a slow-growing, non-life-threatening type that doesn’t need to be treated.

Treating them is not harmless. “Virtually all the people diagnosed with thyroid cancer are treated,” the New England Journal article notes. Surgeons usually remove the thyroid gland, totally or partially, and patients must take thyroid hormone supplements the rest of their lives, often with difficult side effects.

More than one Korean thyroid-surgery patient in 10 suffers damage to the nearby parathyroid glands, which causes difficult-to-treat abnormalities of calcium metabolism. Two in every 100 patients ends up with paralyzed vocal cords from surgical mishaps.

But clearly, South Korean doctors and patients find it almost impossible not to treat a cancer once it’s diagnosed.

It’s similar to long-running arguments in the U.S. and other countries about who should get mammograms to detect early breast cancer, or PSA tests to spot suspicious prostate tumors.

Welch is no stranger to over-diagnosis debates. He co-authored a controversial article two years ago that claimed many of early breast tumors revealed by mammography don’t need to be treated at all.

Mammography screening is a less clear-cut issue than thyroid cancer ultrasound. There’s more evidence that mammography saves some lives. The controversy is more about who should be screened, how often, and what to do about a positive mammogram.

Screening for cervical cancer is on the other side of the ledger. It’s the epitome of a cancer that should be screened for, because the payoff is so clear.

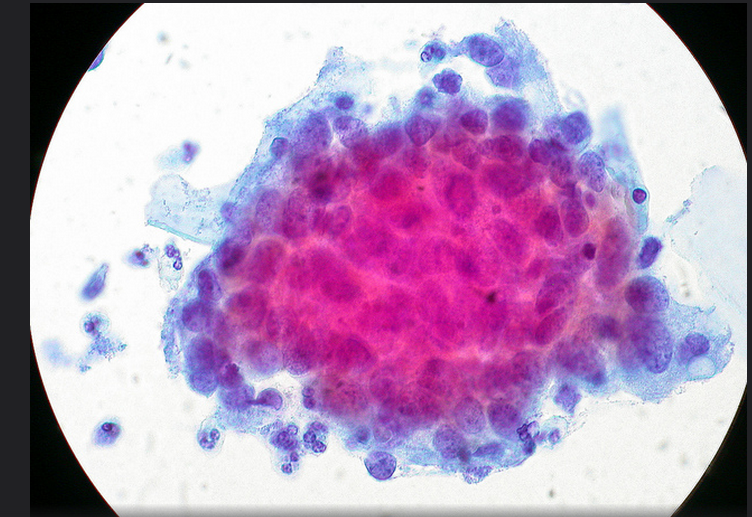

When the “Pap” smear was introduced in 1950 (named after its inventor, Dr. George Papanicolaou), cervical cancer was the number-one killer of American women. Now it’s not even in the top 10.

No malignancy is more preventable than cancer of the cervix. But more than 12,000 U.S. women still get it every year, and more than 4,000 die from it.

“No woman should ever die from cervical cancer,” Ileana Arias of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told reporters in a Wednesday telephone briefing.

But a new CDC report shows that more than one woman in 10 isn’t getting screened for cervical cancer.

Among women who lack insurance or a regular health care provider, one in four hasn’t been screened in the past five years.

It’s a fixable problem. A Pap smear every three years between the ages of 21 and 65 can spot cervical malignancies – and pre-cancerous abnormalities – in time to prevent life-threatening disease, or head off cancer entirely.

Unlike thyroid cancer, over-diagnosis of cervical cancer is not a problem. Every abnormal result needs to be followed up by a repeat Pap smear in 6 to 12 months, and the most suspicious results justify a biopsy to determine if treatment is needed.

A relatively new test that identifies women chronically infected with cancer-causing strains of the human papilloma virus (HPV) adds another layer of early detection. It’s for women over age 30.

Incidentally, public health experts think that a vaccine against HPV, given to teenagers, could virtually eliminate cervical cancer along with cancer of the penis in men. But the CDC says 60 percent of adolescent girls and 86 percent of boys aren’t getting vaccinated.

Taken together, screening for thyroid and cervical cancer show that not all screening is equal. Like so much in medicine, it's complicated, and the pros and cons of each need to be weighed with care.