Advertisement

Dick Lehr: From 'Whitey' Bulger And 'Black Mass' To D.W. Griffith And 'Birth Of A Nation'

Dick Lehr is a calm spoken, reserved person who has walked the in the footsteps of some of the edgiest sociopaths of our time.

He is best known for "Black Mass" (2000), the acclaimed chronicle of "Whitey" Bulger he co-authored with Gerard O'Neill, which, as you know from all the traffic-halting filming and Johnny Depp sightings this summer, is finally getting spun into a movie.

In "Judgment Ridge" (2003), Lehr, and co-author Mitchell Zuckoff, explored the heinous thrill-kill murders of Dartmouth professors Half and Susanne Zantop in their remote New Hampshire home.

And back in 1979, when working at the Hartford Courant, Lehr infiltrated a meeting of David Duke and the KKK in Danbury, Connecticut, to debunk Duke's claim that the Klan had a large and growing membership within the Nutmeg State.

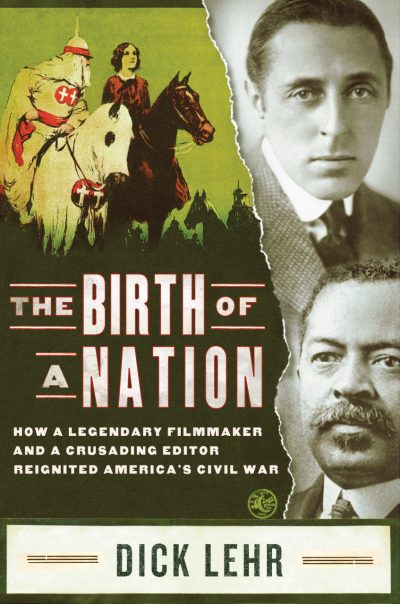

Lehr's latest, "The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Director and a Crusading Editor Reignited America's Civil War," rewinds history back to 1915. It explores the conflict that played out between the groundbreaking director D.W. Griffith — whose notoriously polarizing film "Birth of a Nation" was on the verge of becoming the original blockbuster — and journalist and activist William Monroe Trotter.

"Who?" you might ask. Lehr himself had no idea and simply stumbled upon the name. "As a newspaper guy, I was kind of embarrassed I didn't know, but Trotter was up there with Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois," Lehr says of the prominent black activists of the time.

Trotter had founded The Guardian, a modest African-American newspaper in 1901, and in its inaugural issue, took Washington to task for having dinner with the then president, Theodore D. Roosevelt—something that Lehr poses as an event that most progressive minds embraced as an important step forward.

The heart of Lehr's narrative, however, centers on the release of Griffith's film in Boston, the massive protests and the intriguing interpretations and twists of the First Amendment. The background that Lehr, a former reporter at The Boston Globe and current journalism professor at Boston University, lays out is riveting.

Lehr, who has an admitted penchant for confluence and circumstance, sets the stage richly by delving into his protagonists' portending crisscrosses over time. Griffith's father, Jacob, was a Civil War hero for the South, while Trotter's father, James M., served in 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a unit similar to the all-black regiment depicted in the 1989 movie, "Glory."

Advertisement

Griffith exhibited his film to President Woodrow Wilson at a private screening at the White House in 1915. The year earlier, Trotter had led a delegation down to Washington to have a “discussion” with Wilson about Jim Crow laws, and was subsequently thrown out.

Griffith, long before assuming the director's chair, existed mainly as a struggling actor, and during one tour, for a one month stint, performed at a theater in downtown Boston that was along Trotter's path to his work at The Guardian. But even more coincidental and ironic, Griffith had legally wrangled with a board in Ohio to include “film” under the banner of the First Amendment as a medium of freedom of speech that could not be censored. (He lost — at the time, Lehr points out, the First Amendment applied mainly to the press, not art, literature or theater.) And Trotter, treading on that same legal precipice, tried to get Griffith's cinematic, racial superiority propaganda banned in the Hub.

For Lehr, writing the book had an element of serendipity as well. When at that grange in Danbury, Duke showed the sprinkle of KKK recruits "Birth of a Nation" while orating (the film is silent) his divisive message to the audience. During his research, Lehr, as a “newspaper man,” found himself a bit surprised at Trotter's burning intent to censor Griffith, especially given his role as a journalist and activist actively championing free speech and equal rights. "It was something I really struggled to find balance with," Lehr notes.

As with all his works, Lehr tries to put himself in the shoes of his subjects, going to the places they frequented and cherished. "It's essential," Lehr says, "to get the details right to let people know what it was like to be there back then." The book holds many such nuanced immersions into the time and place. The breadth and depth is great and meticulous, and it captures a righteous occurrence of civil disobedience in our city's rich past while revolving around an esoteric figure who, thanks to Lehr, should become less so now.

"The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Director and a Crusading Editor Reignited America's Civil War" came out earlier this month. (And coincidentally, "Black Mass," opens at theaters in 2015 — exactly 100 years after Griffith's "blockbuster.")