Advertisement

Brutal Gang Violence Reigns In El Salvador

Part 1 of a series on gang violence in El Salvador and those fleeing it to Massachusetts

SAN SALVADOR, EL SALVADOR — In a country with all the sun and verdure of an idyllic resort, but none of its safety, new white vans and pick-ups convey a steady supply of corpses through the crowded traffic of San Salvador, the capital city, to the Office of the Medical Examiner. Fifty-two murders in 72 hours, said local newspaper headlines on Nov. 18.

If you want to know why so many Salvadorans are running north this year, the medical examiner's receiving room seems a good place to start. The victims keep the metal autopsy tables and attending doctors at full capacity. On display are the youth of El Salvador.

“Seventy percent of the people who are killed are between 15 and 30 years old,” Dr. Miguel Enrique Velasquez says in Spanish.

According to a recent report from UNICEF, El Salvador has the world's highest rate of homicide for children and adolescents. And it’s rising.

“We are taught by nature that children bury their parents, but here in El Salvador it’s the opposite,” reflects the doctor in a slightly weary voice. “Here the parents bury their children.”

Many of the murders stem from the brutal violence of criminal gangs at war with each other and with El Salvador itself. I ask the chief medical examiner, Jose Miguel Fortin, if there is a distinguishing sign when murders are committed by gangs.

Yes, he says. When a head is found but no body, he says, that’s a gang murder. When there is a body, but it’s been dismembered, that’s a narco-trafficking murder. And when the body was dismembered while the person was alive, that’s a Mexican narco-trafficking murder.

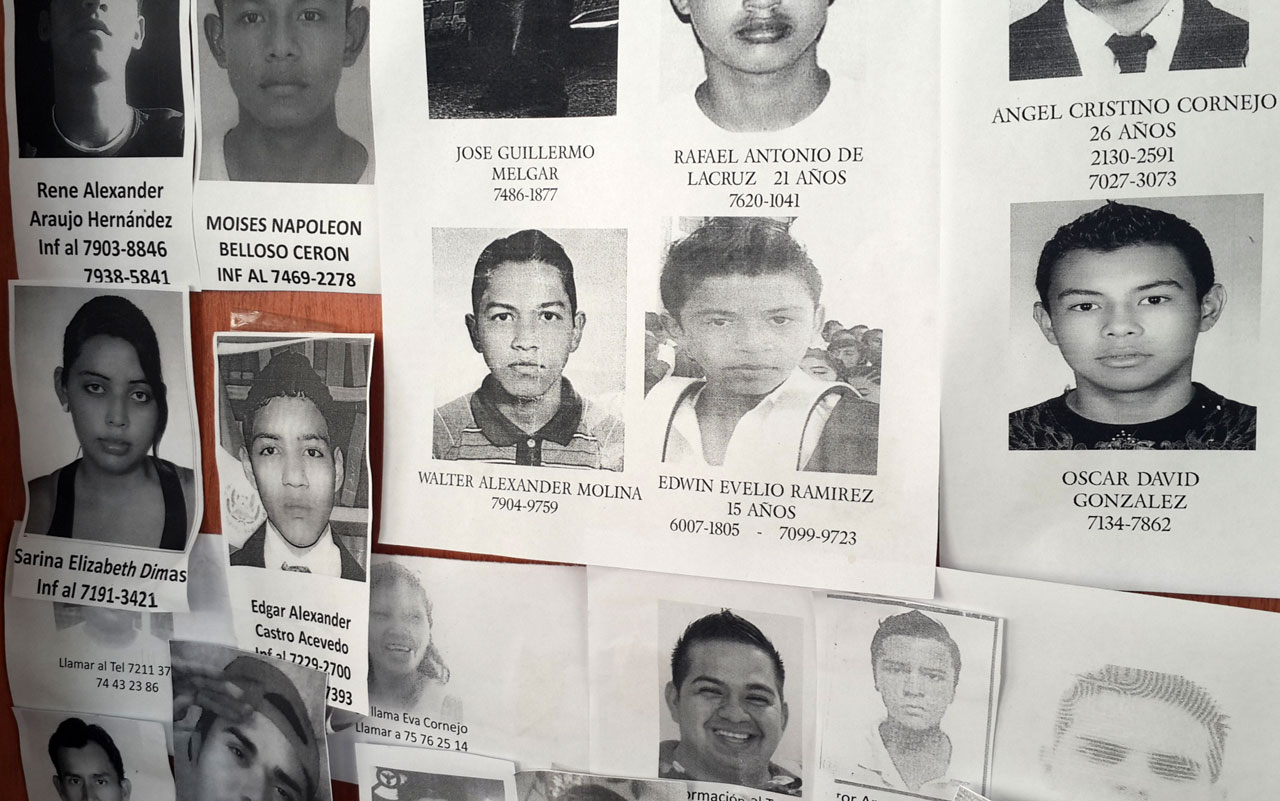

Laid out in the room next door, old bones from once-hidden graves are assembled into skeletons. Forensic anthropologists sort through a sea of unidentified remains in a country with a sea of disappeared ones, “the desaparecidos." In a courtyard in the complex of buildings, families of the missing post their photos in the hope that they might be matched to old bones, and thereby found.

Advertisement

Marked Forever

In the densely packed slums of the municipality of Mejicanos, National Police Inspector Jorge Alberto Vasquez leads a force of 70 officers. With automatic handguns strapped to their thighs and rifles in their hands, they patrol neighborhoods in the foothills of the volcano San Salvador.

“We’re having problems with gangs fighting for territory,” the inspector says as we drive through an open-air market of ramshackle stalls made of corrugated tin and shredded plastic. It’s in the barrios and marginalized communities like this one, where half of El Salvador lives in poverty, that gangs have taken hold like tropical vines.

The two biggest gangs are the notorious made-in-America Mara Salvatrucha, aka MS-13, and its rival, known as MS 18 or 18th Street. They come with assault weapons, many with tattoos etched on their faces.

Our old four-door police pick-up stops near some other police trucks, each with three or four officers. In a neighborhood that’s quiet save for the barking dogs, with the graffiti on the walls newly painted over as part of a community policing effort, the inspector explains that we are in a "zona roja," or red zone. It was once 18th Street territory, but MS-13 is now trying to take over.

“Last weekend in this house [they] killed a woman. A woman was murdered,” he says and then starts pointing.

At a house 50 feet down the street on the same side, people “have been murdered there.” And at a house across the street from that one? “Yes, they have been murdered over here.” And at the corner, just another 50 feet away. Yes, over there too.

When you count gang members, the inspector says, you should add mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters and cousins. Rival gangs think the same way: When one joins, the whole family joins. And so they are marked, and marked forever, according to gang mentality.

The inspector tells me that the woman who died a week earlier first lost a son. He was shot to death by MS-13. Next gang members came for her son-in-law. They killed him too. Then they came back for the woman's daughter. They shot her three times in the stomach.

“I pleaded with the mother,” the inspector says. “‘They’re going to kill you. They're going to kill you.’ “We told her several times, ‘You have to go away.’ And now she’s dead.”

At the thought that she ignored his advice, the inspector adds: “It seems like people are resigned to their death; they know it's coming for them.”

More Flee El Salvador

In El Salvador’s civil war that raged from 1979 into the 1990s, Mejicanos suffered some of the worst fighting. Across the nation right-wing death squads and Army soldiers tortured and murdered with impunity. Seventy-five thousand Salvadorans died. Since the war ended, 73,000 have been murdered. Now sons and grandsons of that war's soldiers are fighting this one.

Sandra Serrano is a college student from Chalatenango, a department which suffered greatly during the war. I spoke to her in San Salvador while she was attending a commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the Army murders of six Jesuit priests and two associates known as the martyrs for justice. She linked that era of violence with the current one.

“First there were the death squads and now the gangs, which I think are much worse,” she says. "Gangs are the 21st-century death squads.”

The country is no bigger than Massachusetts, with the same population. Yet in El Salvador, an average of 12 people are murdered every day. And children and their parents are clearly keeping count. As the murder rate rose 50 percent from last year, the number of unaccompanied children apprehended at the U.S. border with Mexico increased by 270 percent (peaking over the summer).

“Fifty-eight percent of children are fleeing from violent gangs,” says Karla Castillo, who helped interview 600 Salvadoran children after they were caught in Mexico and sent back home this summer. “It’s the primary reason they are fleeing.”

Some of the children were as young as 7; most between 12 and 17. Traveling without their parents, they risked murder, kidnapping, rape, beatings and even the danger of falling from atop the Mexican freight train known as “La Bestia" — "the Beast."

Their choice, they told Castillo, was stark: to leave El Salvador or to die.

“The gangs are trying to recruit the children to join the gangs," she says. "And if the children don't join the gang, the gang members are going to kill them.”

Atop a hill facing the volcano San Salvador, Vasquez, the police inspector, points to a large water tank on the summit of another hill. Towering letters and numbers read "MS-13." It's like a pyramid with the gangs on top. But the pyramid must have new soldiers, and so the gangs recruit boys and girls alike at adolescence, even younger. In schools and neighborhoods, they recruit by force. Initiation rites include beatdowns and gang rape and missions to kill rivals.

A glimmer of hope is the fact that so many adolescents have rejected the gangs. The bad news is that they have had to flee their homes for places like LA and Boston. The worse news is that if they are sent back home, they will to face an even bigger danger: the gangs whose threats caused them to run in the first place.

This segment aired on December 23, 2014.