Advertisement

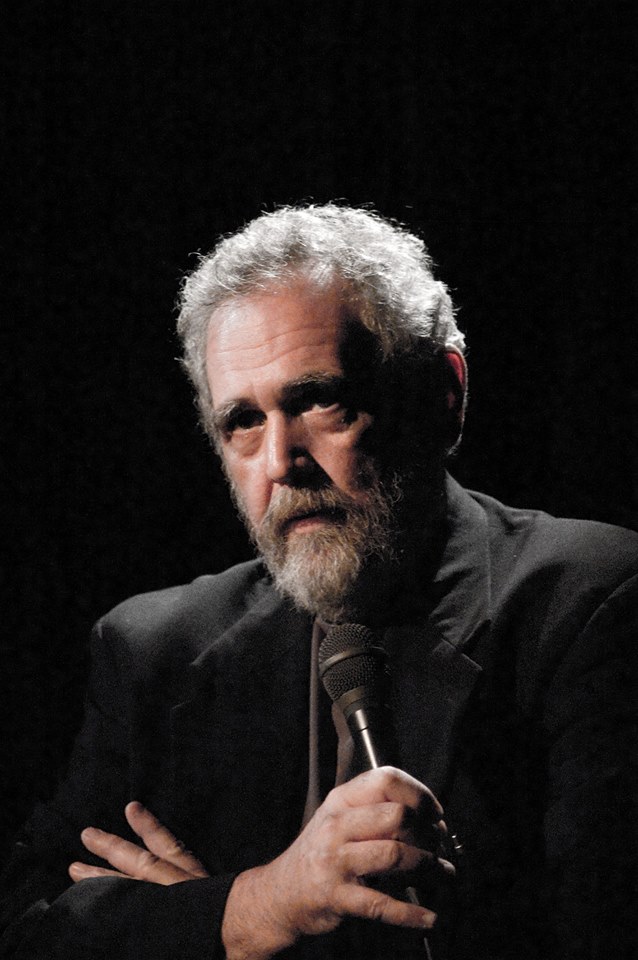

'Call Me Lucky' — Bobcat Goldthwait's New Film About Longtime Friend Barry Crimmins

"Call Me Lucky" will be playing at the Somerville Theatre in a special engagement starting Friday, Aug. 21.

This piece was originally published in December 2014.

Earlier this year, director Bobcat Goldthwait was looking through some old video from “Comic Strip Live,” a comedy show that ran on Fox from 1989-1994. He watched Barry Crimmins, his good friend and peer from the Boston standup comedy boom era of the ’80s, riff for six minutes.

“There’s some footage I really love, where Barry’s on this show—in Hollywood, on Sunset Boulevard, live on national TV—doing a set and he starts doing political humor,” says Goldthwait, on the phone from Atlanta, “He’s doing well, but then he starts getting some groans.”

How did Crimmins respond?

“He breaks down the HUD scandal!” Goldthwait says, with a laugh. (The Reagan-era HUD scandal was a complicated mess—fraud at the agency, political influence peddling, waste and mismanagement.) “To me, that represents Barry: He could have been a much more-known comedian, I believe, but what he had to say was more important.”

“I know how to do strong standup comedy and I have done it well,” says Crimmins, in a separate interview on the phone from his upstate New York home. Crimmins’ earlier material was not as overtly political, but, he says, “slowly it dawned on me the American people are too distracted; there are too many diversions. I wasn’t going to participate in that. I would do something in my act to establish, ‘This guy’s funny’ and get them and slowly move into...death squads. It’s a slow process of learning how to smuggle content to people.”

Last February, Goldthwait started shooting “Call Me Lucky,” a documentary about Crimmins, left-wing comedian, satirist and human rights activist. Earlier this month, the film was accepted in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, which runs Jan. 22 – Feb. 1.

Goldthwait believes Crimmins’ stock will rise after Sundance. Goldthwait shot the film in Boston, Los Angeles and in upstate New York, with many fellow comics chipping in for commentary. The film, although only 80-90 percent completed, was one of 16 films accepted in the Best Domestic Documentary category. “As I was submitting,” says Goldthwait, “I was giving them newer and newer cuts so they could see there was a curve.”

“I really felt it was a longshot,” he adds. “I was really shocked and, of course, I’m thrilled that we got in. Normally that’s how most of my movies get picked up [for distribution], through the film festival circuit. This is the big daddy so I’m excited about that. I’m not that jaded. This is the third movie I’ve had at Sundance, but I’m through the moon and really excited to go and watch it with Barry. I believe in the movie and I believe in Barry, but also his story is a big story.”

Goldthwait was 16 when he met Crimmins, who was hosting an open mic night at a comedy club in Crimmins's then-hometown, Skaneateles, N.Y. Crimmins turned the mic over to Goldthwait and Tom Kenny. “He put us on stage and changed our lives,” says Goldthwait. “That’s what launched both our careers, Tom’s and mine. Tom talks about that in the movie.”

Crimmins, now 61, has a high profile in Boston. He moved to the area in 1979, and shortly thereafter founded the Ding-Ho comedy club in Cambridge. It became the launching pad for Boston’s comedy boom of the next decade. Denis Leary, Jimmy Tingle, Paula Poundstone, Lenny Clarke, Steve Sweeney, Mike McDonald and Goldthwait, among many others, honed their chops in the tiny, boisterous room.

Over the years, with his biting, acerbic wit, coupled with a sense of compassion rarely seen in standup comedy, Crimmins carved out a spot as the country’s sharpest, left-wing comic, opening tours for like-minded musicians Jackson Browne and Billy Bragg.

Both Crimmins and Goldthwait concur that Crimmins’ national profile, right now anyway, is not high. Goldthwait says he approached the movie assuming no one in the audience will know Crimmins’ history.

“We’ve been looking at the movie as if we were people from England watching this,” he says. “First, they have to learn Barry, who he is. They have to learn about his comedy and how he was responsible for the Boston comedy scene explosion. We try to do that in an entertaining and funny way.”

Indeed, the documentary traces Crimmins’ rise through the world of political comedy, but it has a profound twist—which we’ll get to momentarily. Says Crimmins of that twist: “Goldthwait’s a genius and he’ll hit the remote control belly opener on the Trojan horse.”

The original plan was to make a narrative story, hiring an actor to portray Crimmins. “I wrote a script and it fell prey to all the problems inherent to me,” says Crimmins. “I just wanted to include everyone and not leave anybody out. Apparently, you can’t make a 307 page script as an independent movie. Bob, I’m sure, didn’t want to tell me I was an idiot.”

The game plan changed this way, explains Goldthwait. “My friend Robin Williams suggested that I do it as a doc and in fact he gave some of the initial money that I needed to start the movie with. And now the movie is going to be playing in the same theater that ‘World’s Greatest Dad’”—a brilliant, dark comedy released in 2010 starring Williams—“appeared in.”

“I think the emotional impact at Sundance, seeing it in the theater with Barry will be exactly the way I watched ‘World’s Greatest Dad’ with Robin. Robin hadn’t seen the cut of the movie and so we sat there and it was emotional and rewarding. Over the years, I’ve been to a ton of Robin’s movie premieres and a good majority of them I’ve sat with him. He’d be very quiet watching them and when we watched ‘World’s Greatest Dad’ he just sat there cackling like Robert De Niro as Max Cady in ‘Cape Fear.’ Laughing out loud. And he was very moved. It was a big deal for me. I’m hoping I have a similar experience with Barry.”

And now, the wrenching twist—which is in some ways not a twist, because it’s something Crimmins has been long public about: He was repeatedly raped when he was a young child by an adult who came to his North Syracuse home after a certain babysitter arrived.

“I broke silence about this over 20 years ago in a Boston Phoenix piece,” Crimmins continues. “I’ve had years to get used to it. I’m someone publicly disclosed. Many people have said, ‘It took a lot of courage to admit you were abused.’ No. Guilty people admit things; crime victims expose and testify.” (Crimmins’ assailant served time in a New York prison for similar offenses and died while incarcerated.)

“I have no problem letting that out of the bag,” says Goldthwait, talking about the twist. “It’s part of why Barry’s a hero and also, as Barry says, ‘If you’re going to tell anyone, tell everyone.’ And that, at the end of the day, the message of the movie is not being afraid to discuss and fight sexual abuse. The whole beauty of Barry’s story is that even though it’s a tough childhood, it’s also very funny and there’s cheer along the way.”

Still, Goldthwait notes, “my sound guy Frank Montes, in the middle of one of the interviews, stops and says, ‘This is the darkest movie you’ve made.’ I don’t like using the term ‘dark,’ but there’s stuff that seems very dark. Three of the movies I made were dark, but then they had very hopeful messages.”

“Call Me Lucky” won’t have the usual rise/fall/rise arc of your typical bio-pic. “I’m glad there’s a more jazz rhythm to my life,” says Crimmins, who after leaving Boston in 1993, spent time in Ohio, before resettling in his native upper New York state in 2000.

Juggling the varying tones in the movie, says Goldthwait, “is a bit of a Rubik’s Cube, trying to put all the pieces together and keep the running time an hour [and] 40-45 minutes." Crimmins says, "That’s where Goldthwait’s genius will come in.”

Goldthwait says he himself appears a bit in the film. “Very sparingly. There are certain people who make documentaries that I enjoy who show up in the movies like Michael Moore and Nick Broomfield, but then there’s that other thing where sometimes the film-maker makes it about themselves and I wanted to avoid that. I am part of Barry’s life and I am part of his story, so I show up sometimes, but it’s not about my journey discovering Barry. It’s Barry’s story, and then, at the end of the day it ends up being a more universal story for everyone.”

Crimmins hasn’t seen any of the movie. But Goldthwait says, “There is a surprise cameo. At one point, Barry says ‘I’m such a bad actor I’m going to get cut out of my own documentary’ and then suddenly I cut to an actor playing Barry.”

If you’re wondering where the film’s title came from, it’s a phrase Crimmins keeps coming back to. “In this life you have to go through things and not around them,” Crimmins says. “Maybe if there’s a takeaway from this movie, it’s ‘Here’s someone who went through what he had to go through.’ I lost so much time to this when I couldn’t do anything about it; once I could do something about it I did. It wasn’t like I cut any corners. I didn’t really malinger and go ‘woe is me’ and that’s why it’s called ‘Call Me Lucky.’ I became a human rights activist rather than a perpetrator of human rights offenses.”

“For whatever reason. Who knows? Your life gets skewed by this stuff, but would I have as much compassion for other victims of injustice as I’ve had? And that leads me to [learning from and becoming friends with] Howard Zinn and touring with Jackson Browne and Billy Bragg. All these other amazing things I’ve been able to do and that fortified me, and made the weave of my life stronger so I could handle things I needed to handle. When the time came, I could go through things and not around them.”

(Full disclosure: Having covered Crimmins while at the Boston Globe, and getting to know him off-stage as well, I was interviewed by Goldthwait for the film in Charlestown.)