Advertisement

Guitar Hero And Songwriter Richard Thompson On Folk Music: ‘It’s Very Addictive’

Few musical introductions have marked me as indelibly as my first encounter with Richard Thompson. It must have been around the time that “Action Packed: The Best of the Capitol Years” came out in 2001, because I remember the cover art vividly: a surreal collection of little guitar-wielding Richard Thompson action dolls arranged, like so many vacant-eyed geese, in an aimless flock. My father, a Thompson aficionado (Thompsonite? Thompsonhead?) had popped the CD into the car stereo in the hopes of converting me. I was probably 14 at the time. The thing that stood out to me was his voice, which is astounding: booming and thick, a little eggy, even. I confess to not liking it much then.

As the years passed, Thompson’s music remained a steady, insistent presence in my life. This was mainly due to the fact that musicians love to cover his songs: Elvis Costello, R.E.M., Robert Plant. Thompson’s compositions tend towards the brooding and the difficult, like “Beeswing,” a wistful folk ballad in which a man falls for, and loses, a free-spirited hippie. In Thompson’s hands the story is not saccharine but gently melancholy, like the woman he describes in the song: “Oh she was a rare thing, fine as a bee’s wing ... She said, ‘As long as there’s no price on love I’ll stay/ And you wouldn’t want me any other way.’”

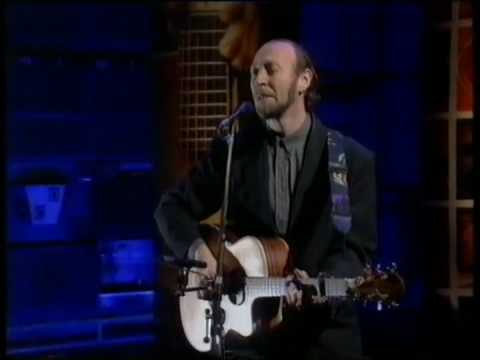

Thompson, who plays the Wilbur Theatre in Boston on June 20, got his start in 1967 with the English folk-rock phenomenon Fairport Convention. He left after a few years to pursue a project with his then-wife Linda, a successful endeavor that nevertheless ended with the marriage. Since then, Thompson has steadfastly produced album after admired album, earning him a reputation for underratedness even as he has amassed a dogged following. He has been the recipient of many awards, both official and not, including countless Grammy nominations, the Order of the British Empire and No. 19 on Rolling Stone’s “100 Greatest Guitarists: David Fricke’s Picks” in 2010. Just as songwriters admire Thompson for his lyrics, guitarists revere him for his six-stringed perambulations. His is a sly virtuosity, his playing is as effortless and expressive as his words.

Thompson’s newest album, “Still,” is a prototypical Thompson product: energetic, economical and song-focused. It was produced by Jeff Tweedy of the indie rock band Wilco and recorded quickly in his Chicago studio with Thompson and a bare-bones ensemble of bass, drums and the occasional second guitar. Thompson’s singing seems only to have gotten freer and more pliable with age—a metaphor, perhaps, for his career, which has never suffered from fussiness or crass calculation. Thompson, as always, strides eagerly forward, ears keenly attuned to the music in his head.

In the following interview, which has been condensed and edited for clarity, Thompson spoke about the recording process for “Still,” inspirations for his songs and the addictiveness of folk music.

I guess just to start I was wondering what sort of vision you had this time around. I mean you’ve made a million albums, I don’t know how you approach it each time.

I love the idea that you think I have a vision. [laughs] You know, this is a collection of songs that I’ve been writing for a few months for the record and I don’t think there’s any sort of thematic link between them. I think when you write songs in a short time period, they kind of sit next to each other. There’s kind of a commonality to them. Not thematic, but just the fact that they’re written around the same time means that sometimes they kind of share melodic ideas, they share harmonic ideas. So I feel this is an album of songs and I think if there were any songs that didn’t feel like they belonged they got filtered away a long time before the recording process.

I was reading another interview with you, and it just seems like you’re not super precious about each album. Maybe I’m wrong about this, but you just put them out, and you make them quickly, and they exist the way they exist. Your feeling about them seems different from some people, [who think] “I have to be perfect.” Do you know what I mean?

I’m probably not a perfectionist in the studio. That could be a good thing or a bad thing. If you want to sell lots of records I think it you might be more perfectionist. I like albums slightly rough around the edges. Just ‘cause I think there’s more energy in that. It’s good to capture something fairly live in the studio, if possible. ... If it isn’t perfect, at least you capture the spirit of something. Rather than you going over it and over it and over it. You know, some people have a talent for working in the studio for a long time, and producing something that still sounds full of energy. And that’s kind of a trick—you have to recreate the energy of a live performance in the studio. You know, some people can do that. But I can’t do that. So I just have to work quicker and smash it down quick and hope people like it, warts and all.

For you, is live performance the best place to communicate your music? Is that your preferred mode?

I think for me playing live is the best thing. In front of an audience, to play a concert, is kind of the fulcrum of the whole process. I think records are slightly artificial things, in that you don’t really have an audience but you simulate the energy in the studio. You play for each other, really, I think, in the studio. So I think records are something that hopefully attracts people to a concert, rather than the other way around.

I was wondering if you could tell me more about your relationship with folk music. Only because I find it very interesting that you’re very steeped in a lot of rock, and blues, and you clearly have studied a lot of different vernaculars and types of music. And I can always hear, even in a song that to me sounds like a rock song, I hear a lot of folk melodies and stuff like that. And I wasn’t quite sure for you why that stuck around, or why that resonated, and is still so present in your music.

Yeah, I don’t relate to rock music particularly. I never listen to rock music. I listened to rock ‘n’ roll as a kid, that was exciting stuff. But I’ve always been really interested in traditional music. So I think in my songwriting, it refers to tradition a lot. You know, particularly Celtic tradition, Scottish, Irish, English traditions. I’m always sort of playing a magnified folk song, as far as I’m concerned.

I don’t know if you can say a bit more about why folk music is what you like—especially because you clearly have so much appreciation for guitar players, and electric guitar players and people working not in the folk idiom.

The nice thing about a musical tradition is that it resonates. There’s a reverberation throughout history. You might sing a line, you might compose a line that’s a twist on something you heard in a song from the 18th century. And for you, you know the connection. And maybe the audience does and perhaps they don’t, but that doesn’t really matter. It’s satisfying for you to feel a part of this thing that’s hundreds and hundreds of years old. And I still sing sometimes, I sing traditional songs from maybe, you know, the 1600s. And it’s an endurable thing, it’s a pleasurable thing. And once you get kind of placed in that tradition it’s very addictive, and something that you never want to let go of.

Going to your songs: They don’t always necessarily seem autobiographical to me, and to assume that somebody’s songs are literally their life is obviously not true most of the time. And you do—again, going with the folk thing—tend to focus on narrative, and character, and story. And I was just curious how you develop those ideas, where they come from.

I think I like different kinds of songs. There really are songs that are autobiographical or a fictionalized version of that. And there’s other songs where I just sit down and start writing and I don’t really know what I’m doing. And then I’ve written something and I look at it and think, “Wow.” [laughs] “Where did that come from?” And that’s kind of fun to surprise yourself by some kind of, you know, stream-of-consciousness. But sometimes it makes interesting songs, and perhaps sometime down the road you think, “Oh, actually, I didn’t understand it at the time, but I now see what that song is about. It’s kind of about me.” Most songs are about you in the end.

It seems like there are some reoccurring characters ... “[She Never Could Resist A] Winding Road,” on this one, reminds me of the woman in “Beeswing.”

It’s not something that I analyze too much, or that I want to analyze too much. The character in “Beeswing” is a certain kind of wild spirit. And again, it’s based on people I used to know, particularly in the ‘60s. It’s a real ‘60s song about people trying to leave the urban environment and trying to lead a freer lifestyle in the country. That was a very common thing in those days. That character was being very typical of that time. A character in a song like “She Never Could Resist A Winding Road” is about someone I know, that’s very close to me. And absolutely that’s her character. She just has itchy feet. And it’s not an urban-to-rural thing, it’s a thing of, “I’ve been sitting still for two days, I really want to go somewhere.”

And I think I love both characters. I have an affection for them, I have an affection for their lifestyle and their needs. It’s that thing of, you can’t tie people down to what you want. You have to let people be who they are. The commonality in those two songs I think is that ... sometimes things in life are elusive, so you enjoy them while you have them. But you can’t hold them, you can’t keep them. You have to let them be what they are and let them be free on their own terms.