Advertisement

'King Lear' Reigns — And Rains — On Boston Common

“King Lear” is kicking up a storm on Boston Common (through Aug. 9). And what a storm it is, replete with claps of thunder, wind cranked from giant fans, swamps of fog and arching streams of water that leave the actors soaked to the skin. And in the midst of it all rages possibly the greatest play ever written.

Commonwealth Shakespeare Company celebrates its 20th anniversary of free Shakespeare on the Common by rushing bravely into the breach (as Henry V would say) of this most devastating of Shakespearean tragedies. Some critics (among them Yale luminary and “Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human” author Harold Bloom) consider it monumental but unplayable. Not being an armchair Shakespearean, I certainly do not hold with that.

The play is a juggernaut, albeit a complex one presciently and wrenchingly weighted by existential discovery. Its inevitability is set in motion when the medieval king of the Britons unwisely divvies his kingdom among his daughters — two of them flattering snakes, the third refusing to fawn and thereby incurring the disinheritance that will prove fatal to both her and her ravaged dad.

On Boston Common, where the piece must be broadly enacted and heavily amplified to reach the multitudes, the furious conflict between good and evil forces necessarily trumps the play’s more touching considerations of human fragility. But the Bard’s poetry, mighty and mordant, rings loud and clear — and nowhere more loudly and clearly than from the highly-rated larynx of Will Lyman, its vigorous Lear (whose foreboding gaze is spread across a string of upstage banners that are yanked to the floor as the commanding if imprudent king comes apart).

Of King Lear, actors say if you wait until you are old enough to personify the octogenarian monarch “more sinned against than sinning,” you will lack the strength to withstand the vocal and emotional demands of the role. CSC vet (and chairman of its board) Lyman, 67 (and a friend of mine), can still carry the ranting, then the humbled arias and the corpse of Cordelia.

Best known as the authoritative voice of “Frontline” and the narrative chronicler of Dos Equis’ Most Interesting Man in the World, Lyman has the pipes, the smarts and the stamina. When this vocally eloquent actor, whipped about the heath in the gale, commands the winds to blow and crack cheeks, you figure they better bloody well do it.

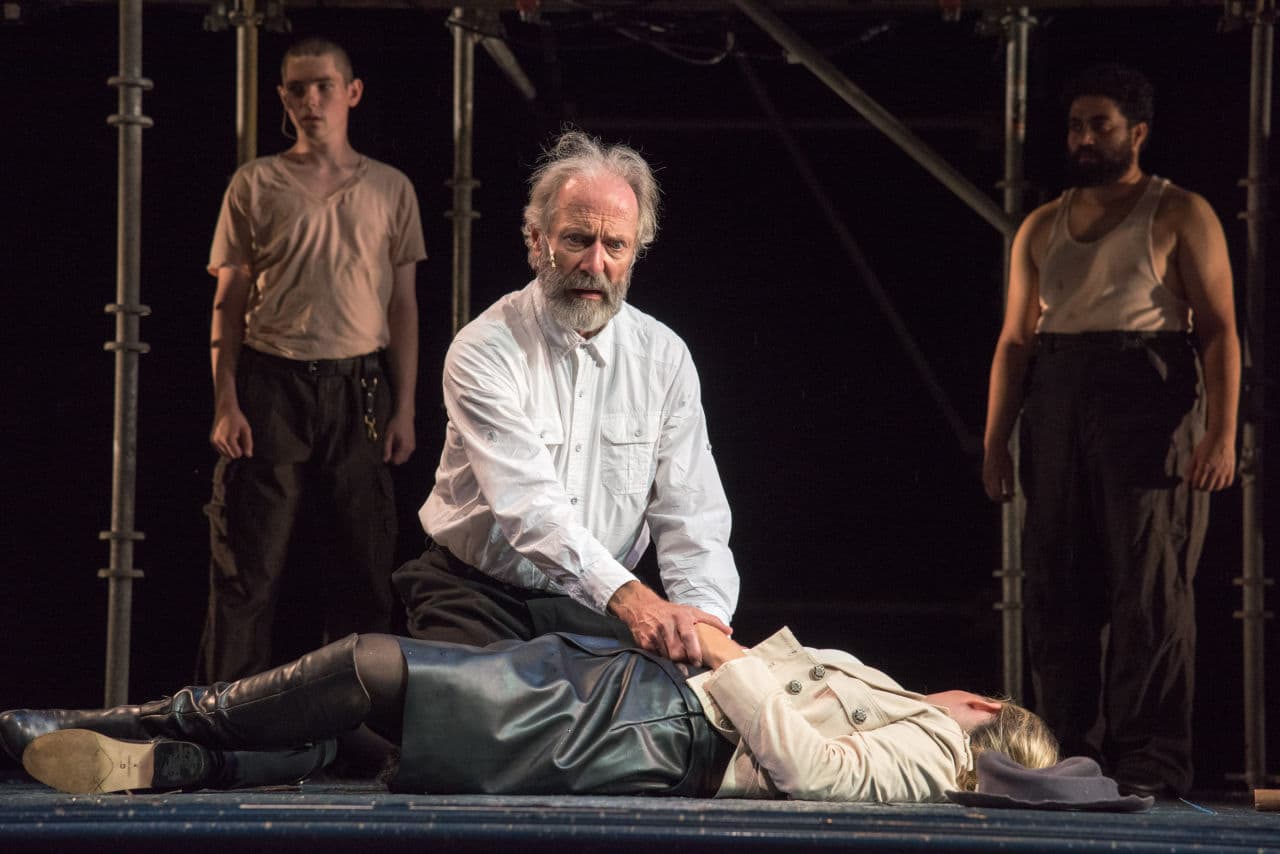

Lear’s speeches are filled with vivid, sometimes animalistic imagery (and, as he is serially affronted by the ungrateful daughters, no little misogyny), and Lyman never struggles. If there is something missing of the pathos of the broken king, giving in to the madness and dotage against which he has so long railed, that is more blamable on the vast outdoor arena than on the actor. And even so, the reunion of Lyman’s tremulous king with his better daughter wrung from me the tears Lear so abjures.

Director Steven Maler, here helming his 20th CSC production, makes no attempt to reinvent the wheel so often invoked in the play. This is a solid, rattling staging, suggesting time periods ranging from the 19th century to the power-suited present (sometimes merging eras, as when Fred Sullivan Jr.’s avuncular Duke of Gloucester, gotten up like an Edwardian gentleman, shares a wallet snapshot of his son). Of course, “King Lear” is as exhausting as it is magnificent, so be cautioned that the show is three hours long.

Advertisement

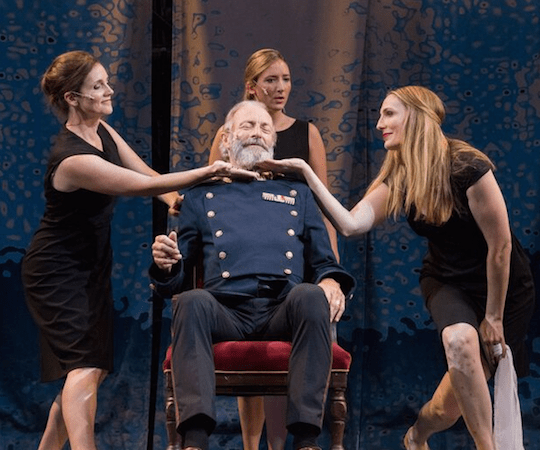

The production is introduced by a courtly pageant set against a dissonant string quartet by British composer Gabriel Prokofiev, recordings of whose aptly agitated music are threaded through the production. Choreographer Yo-el Cassell’s dance begins with Lear in a terpsichorean swirl of daughters but ends with the king blindfolded and thrust into the air. If this is a dream, Lear learns nothing from it, proceeding to disinherit the honest Cordelia and divide his realm between the meaner Goneril and Regan. The fatal flaw in this scheme is that Lear expects to retire from “cares and business” while remaining “every inch a king,” complete with boisterous retinue and the right to command. It is not until much later that, having battled daughters and the elements, he comes to understand mortality stripped of pomp: “They told me I was everything. ‘Tis a lie, I am not ague-proof.”

But there is more to “Lear” than Lear. In this production, the women— even Cordelia — are formidable. Deb Martin is a tough and sensuous Goneril; Jeanine Kane a coolly impregnable Regan; and Libby McKnight a Cordelia more martial than dewy. Sullivan’s fine Gloucester, humane if duped, reacts to his blinding with blood-curdling anguish, and his tears at Dover are likewise convincing. Jeremiah Kissel enlivens the Lear-loyal Kent, a character who can be as boring as he is noble, with a sly, physical, even antic turn that settles into aching wisdom at the painful end.

Ed Hoopman clambers through his disguised stint as Poor Tom, the “poor, bare, forked animal” in whom Lear finally sees himself, then grows into his part as blind Gloucester’s dutiful, legitimate son, Edgar. As his bastard counterpart, Edmund, a less improvisatory Iago, Mickey Solis is dashing but icy (never more so than when, dangling above the stage, he callously ponders of dueling conquests Goneril and Regan whether to take “Both? One? Or neither?”). To the essential if not hilarious role of Lear’s candid, kibitzing Fool, Brandon Whitehead brings bright green gloves and bow tie, a haunting singing voice and too much unfunny business.

It is famously reiterated in “King Lear” that nothing comes from nothing. Not so here. For precisely that price, Commonwealth Shakespeare Company offers what may be the Bard’s most starkly eloquent achievement. So shell out your nullity and weather the storm.

Carolyn Clay was for many years the theater editor and chief drama critic for the Boston Phoenix. She is a past winner of the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism.