Advertisement

A Futuristic Proposal On Martha's Vineyard: Modify Mouse Genes To Fight Lyme

Resume

Never let it be said that Martha's Vineyard lags behind Nantucket when it comes to novel plans for beating back the Lyme disease that taints the joy of nature on even the most idyllic of islands.

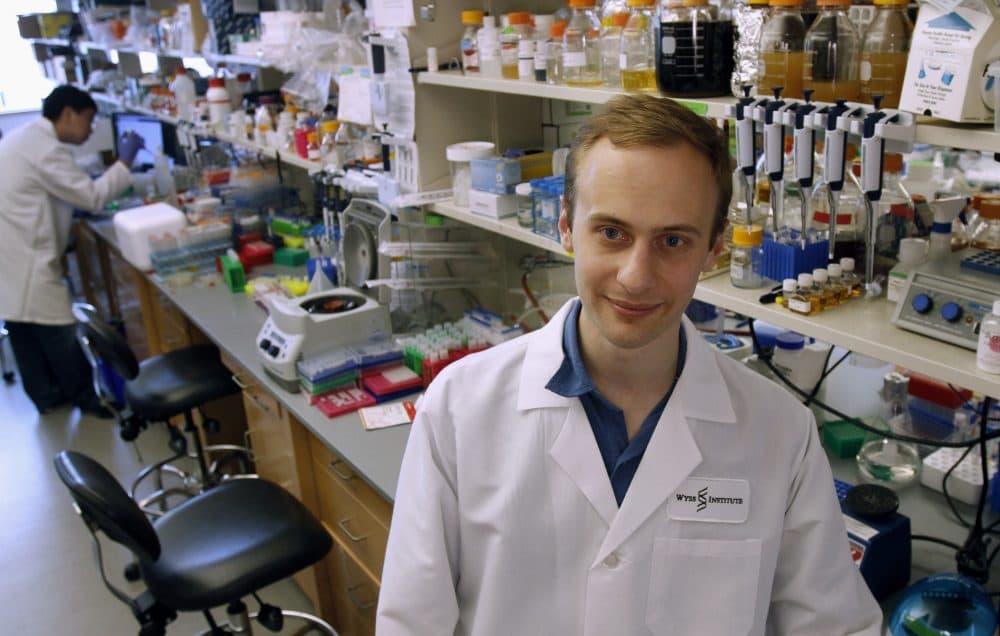

MIT biologist Kevin Esvelt proposed the idea for genetically modifying mice to fight Lyme disease on Nantucket last month. Now it's the Vineyard's turn. Read his carefully phased proposal here.

A couple of updates since we reported on the Nantucket proposal last month:

-- Esvelt says that the feedback is still coming in, but the initial reaction from Nantucket is pushing the project toward aiming to develop mice resistant not just to Lyme disease but to other tick-borne diseases, like babesiosis. They are less common but on the rise, and can cause serious illness.

-- The reception on Nantucket was low-key, but now that the proposal has been covered extensively, Esvelt expects to encounter more "ideological opposition."

-- And a big-picture note: This may be as much a political experiment as a scientific one. Esvelt says it could serve as a sort of a "reset" for the public's relationship with the technology of genetic engineering — dominated lately by questions and suspicions about genetically modified foods.

"If you had to think of a way of introducing a technology that would virtually ensure that people would be suspicious of it, you develop it behind closed doors, by for-profit corporate behemoths that people dislike for other reasons," Esvelt said. "You don't emphasize that you're doing any safety testing at all, and what safety testing you do is largely done by the company itself, by company scientists.

"And the applications of the technology will make money for the company and for the people who produce the food but not for the people who actually eat it. It offers no perceived benefit to the typical citizen on the street whatsoever. So if you want a recipe for making sure people reject a technology, that's it -- that's GMO foods."

In contrast, here's how Esvelt describes the mouse project:

"The long-term goal is to ensure that science is done entirely in the open; that proposals are made public before any work is done in the laboratory whenever the technology could impact the shared environment; and then to come up with a way for communities to weigh in and make decisions from the earliest stages -- to invite concerns from people, even those, especially those who are most solidly opposed on an ideological level.

"Those are the people I trust to go over and check my work, and try to find anything wrong with it that could sink the project. And if they find it, then the project is over. That’s the way it has to be, because as the technology becomes more and more powerful, we need collective scrutiny to ensure that it's safe, and that it's supported."

Ultimately, Esvelt says, managing a powerful technology that could affect a shared environment is a question of governance.

"No one's very happy with our political process these days," he said, "but we haven't come up with anything better. I think everyone would agree we should decide this in New England town hall debate at the local level, rather than handing it over to scientists like me to make unilateral decisions. I’m not for that."

Readers? Do you in fact agree?

This segment aired on July 20, 2016.