Advertisement

'There Is No Yelp': Why Parents Struggle With The State's Special Ed System

Resume

Second in a two-part series. Read part one.

A new report accuses a private special education school in Middleborough of neglect and abuse.

But the Disability Law Center, which on Monday revealed those findings on the Chamberlain International School, says it’s worried about oversight of all such schools serving special needs children.

"We have a growing concern about students with disabilities across the commonwealth being severely mistreated," said Stan Eichner, the center's head litigator. "It’s our sense that the mistreatment of these youngsters with disabilities is not limited to public or private schools, it’s not limited by geography, and we think it’s a widespread problem.”

For parents, figuring out which of these schools is the right fit for their child can be a complicated maze.

This complicated network of schools for some of the state’s most vulnerable students is the focus of an investigation by WBUR and the investigative news agency The Eye.

Number Of Kids With Disabilities 'Increasing Dramatically'

On one of the first days of summer vacation, Marie’s lanky 13-year-old son was cruising around their Norfolk neighborhood on his Razor Trikke.

"It’s kind of the equivalent of an adult big wheel," Marie explained, laughing. "And, you know, executive functioning is a challenge, which means that learning to do something like ride a bike is a challenge.”

We agreed not to use Marie’s last name because of her son's age and to protect his medical privacy.

Her son was diagnosed with autism when he was 2 years old. He also has acute anxiety disorder.

Marie began home schooling her son in the second grade, when the combination of academic and social pressures made the public school environment a difficult place for her son to learn.

The boy was supposed to begin third grade at a special ed program in the Norfolk district. But when his behavior became increasingly aggressive, Marie says the school district could no longer accommodate him.

"The school advised that instead of home schooling or trying to bring him back into the school, they felt it was best that we look for an out placement,” she explained.

There are about 6,000 publicly funded Massachusetts students, like Marie’s son, in out-of-district placements at private special ed schools, commonly referred to as "766 schools" — named after the state's special education law.

If a public school district determines it cannot meet the needs of a special ed student, then the district is required by law to pay for an appropriate education elsewhere.

Students at private special ed schools display a wide range of diagnoses, including autism, severe anxiety or depression.

James Major, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of 766 Approved Private Schools, says students at these schools have complex, severe disabilities — and that can make for a challenging academic environment.

"They usually have failed repeatedly, over and over and over again, and it’s been incredibly frustrating for the kid," Major said. "And our schools really represent the last hope and opportunity for these kids."

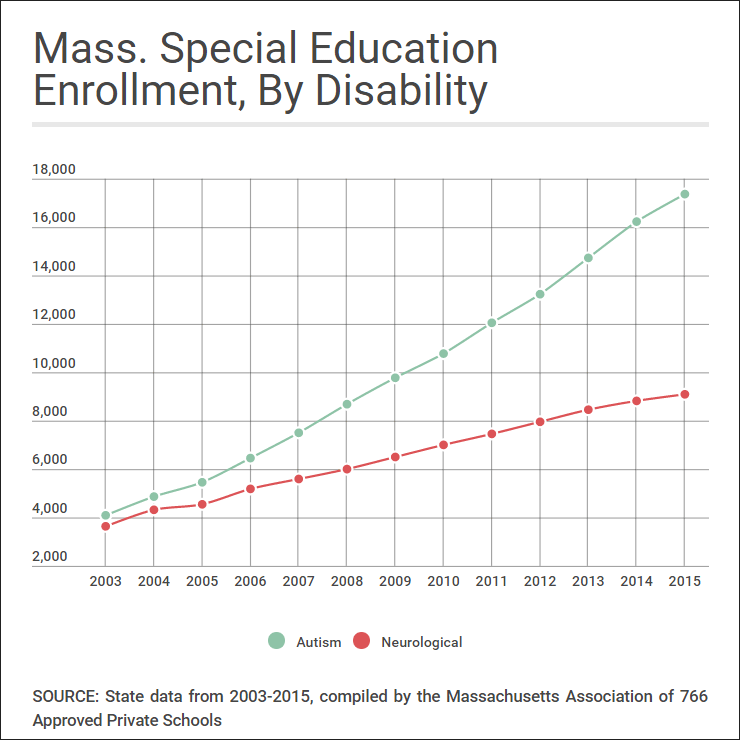

According to state data, the number of special ed students with severe disabilities is increasing. Since 2003, enrollment of students with autism, for example, is up more than 300 percent. The number of students with severe neurological impairments is up almost 150 percent in the same time frame.

"The numbers of kids with complex and severe disabilities is increasing in America and in Massachusetts, and it's increasing dramatically and it’s a real challenge not only to our members but to public school districts," Major said.

Marie says none of the special ed schools suggested by the Norfolk district were appropriate for her son. She says they either didn't accept students his age or didn't take students with his type of aggressive behavior.

At that point, Marie and her husband had to do a lot of their own research — looking online and asking around to other parents.

After trying one school, they ultimately pulled their son when he came home with bruising around his wrists. They began searching again.

“There is no Yelp. I can’t just go online and say, ‘How is this school rated?’ There is nothing out there like that," Marie said. "We're talking about putting our child in a school where they may use restraints, and it was very hard to find out information. Have there been any incidents with any of the children who have been put in restraints? Will my child be safe? And you have to pretty much wait and see what happens.”

Fragmented Oversight

The more than 160 approved private special ed schools in Massachusetts are a mixture of residential and day programs. And they don't just serve in-state students. The system attracts 1,500 out-of-state and international students — bringing $144 million in net revenue into the state, according to the state's trade association.

Massachusetts' special education law was the first of its kind in the country, and the state is largely considered a leader in the field of special ed.

But more than 40 years later some officials and advocates worry that this groundbreaking system has grown into a web of fragmented oversight — making it difficult to easily share information that could potentially prevent mistreatment.

In addition to the report released this week documenting abuse and neglect at the Chamberlain school, the Disability Law Center earlier this year reported that it found examples of neglect by staff at the Evergreen Center, a private special ed school in Milford. The school said it cooperated fully with the law center in addressing its concerns, and the DLC closed the investigation last month.

The law center also found serious mistreatment at a special ed program at the Peck School in Holyoke.

Eichner -- the head litigator at the law center, which is a nonprofit with federal authority to protect the rights of people with disabilities -- says the mistreatment of students at the Peck School was startling.

"Students were mistreated by very large staff members," Eichner said. "One student had been restrained many dozens of times. Many of the students had sustained physical injuries. It was just awful — and this is a public school.”

In a statement, Stephen Zrike, the receiver of the Holyoke School District, said staff at the Peck School are receiving additional training, and there's been a steady decrease in the use of restraints in the program. Zrike said the school continues to cooperate with the law center.

But at the private Eagleton School in Great Barrington, state licensing agencies found the culture of abuse was beyond repair.

The all-boys residential school was put on probation in February in response to allegations of staff punching students, refusing medical treatment and verbally abusing the boys and young men.

State regulators revoked the school's licenses in March and the facility closed in April.

Seventeen former Eagleton staffers now face criminal charges.

Eichner says that school may be a reflection of a larger trend.

"Eagleton represents the state, to some extent, waking up and saying, ‘OK, we have to really do something here, there are big, big problems there,' " Eichner said. "Too many vulnerable students were subjected to conditions that weren’t vigorously overseen or monitored by the state. That was perhaps a watershed moment.”

More Coordinated Monitoring

"Clearly we’ve had some very difficult cases and we want to learn from those experiences," said Maria Mossaides, director of the state Office of the Child Advocate.

Her office brought together representatives from the seven state agencies involved with licensing and overseeing private special ed schools, to look at what more can be done to ensure child safety.

Here’s a quick breakdown of four of those agencies:

-- The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education oversees and approves the actual school.

-- The Department of Early Education and Care licenses and oversees the boarding part of a residential program.

-- The Department of Children and Families is brought in when allegations of abuse or neglect are recorded for children up to the age of 18.

-- But many of these schools offer services up to age 22. So a fourth agency, the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, steps in when someone over 18 is involved in a complaint of abuse or neglect.

And reporting rules vary for out of state students.

"I think the population of children that are now in these schools represent more acute cases than ever before and so it is a good time to look at the protocols and say, ‘Are these sufficient to protect the children who are currently in these schools?' "

Maria Mossaides, director of the state Office of the Child Advocate

Mossaides says she believes this is the first time the state has taken such a deep dive into reviewing oversight of these schools.

"I think the population of children that are now in these schools represent more acute cases than ever before and so it is a good time to look at the protocols and say, ‘Are these sufficient to protect the children who are currently in these schools?' "

That effort includes inter-agency communication — particularly when it comes to sharing reports of abuse and neglect documented at residential schools.

"We need to have a shared understanding of red flags," Mossaides said. "We’re spending a lot of commonwealth activity monitoring, but I don’t think it’s coordinated at the level that it needs to be.”

The state trade association for private special ed schools is also looking at possible improvements, specifically at improving transparency around reporting mistreatment at schools.

After hearing from WBUR and The Eye that parents often struggle to find information about these schools, the group's board voted unanimously last month to approve a framework of proposed state legislation. The bill would call for greater public access to redacted investigation reports at special education schools and other institutions.

'Everybody's Kind Of In Their Own Little Silo'

Back in Norfolk, flipping through her son’s yearbook, it seems Marie and her husband did ultimately choose a great fit for their son. But Marie says it was a difficult road — and she's hopeful that maybe her family's experience can make it easier on other children.

"Maybe I can point somebody in the direction of saying, 'This is how you find out about a school. These are the questions you want to ask when you go. You want to consider distance. These are your child's rights,' " Marie said. "Right now, there's not enough of that that's going on, and everybody's kind of in their own little silo. You know, we're all walking through the same maze but we're not walking together."

And while the state works to improve communication and break down some of those silos, it remains difficult to know exactly what's waiting at the end of that maze.

This article was originally published on August 17, 2016.

This segment aired on August 17, 2016.