Advertisement

How Mass. Teachers Confront Racial Injustice In Class

This is the second part of a two-part report on discussing racial issues in the classroom. Click here for part 1.

Teachers from throughout the state gathered this summer at a middle school in Stoneham to learn how to talk with their students about race. It was part of a program put together by Primary Source, an education nonprofit based in Watertown. Leading the talk was 69-year-old Abby Erdmann, a retired Brookline High School teacher.

“We teach arguing,” said Erdmann, stressing the importance of listening to students who have experienced racism, rather than dismissing or minimizing their concerns. “'Oh, they didn’t really say that to you, did they?' 'They didn’t mean it.' That makes it very unsafe! That makes it very unsafe for people to say things!”

Erdmann never thought she’d be the one teaching other teachers about race. She’s a self-described hippie, and she’s white. But while working at Brookline High, she was struck by a comment a student made about race.

“In the middle of the discussion," Erdmann recalled, "she raised her hand. She went like this: 'Well, race is only skin deep.' And I was like, 'Yes, and no.' And I actually got physically upset with that comment. I was like, 'That is missing so much.' And I was like, 'But I can’t even articulate it.'”

Erdmann decided to learn the right language to use and, as she learned, she shared her knowledge with her students at Brookline High. As part of her work with educators, she often brings former students along to share, in their own words, some of their racial experiences.

Emy Takinami, now a University of Vermont graduate, said that in classroom settings members of minorities are often called upon to educate white people.

“It’s always like, ‘Oh I wanna know, teach me!’ And it’s like, ‘Actually you could be doing this work on your own.”

Erdmann herself doesn’t mince words with her class of educators. She reads from a list of pointers about how to make certain all student voices are heard.

“I have number 6 being a message for privileged white kids, especially white boys, is that they’ve been taught that they’re the most important — and it’s not their fault; they’ve been taught by society, they’ve been taught by their parents, they’ve been taught by their teachers — and they’ve got to learn to listen.”

In light of the public outcry over police shootings of unarmed black men in the U.S. and the uprisings in places like Ferguson, teachers are at the forefront of navigating these subjects in their classes. And, most often, students are the ones demanding the discussion.

Advertisement

Onotse Omoyneni, 17, is a senior at Lowell High School. Last year, the head of school called an assembly after a black student received several racist text messages when he was elected class president. As Omoyneni sat there, she felt that the principal was downplaying the problem, and so she stood up.

“I stood up in the assembly where the headmaster was speaking," Omoyneni said, "and I asked if we were actually going to address the underlying issues. If not, this will continue to happen.”

Brian Martin, the head of Lowell High, said he hadn't realized there was racial conflict within the school. So he listened, and he formed a task force to spark race dialogues. Then he called another assembly — and apologized.

“The first thing I learned was that I underestimated the students," Martin said, "and the fact that there is a voice that hadn’t been heard.”

From Lowell to Wellesley to Boston and beyond, racial conflicts and resolutions are playing out at schools throughout the commonwealth. This summer, at Abby Erdmann’s old school, Brookline High, teachers developed an “Identity Curriculum” to cultivate faculty members' and students' understanding of race and power.

“The United States every 25 years goes through an upheaval when we discover there is racial inequality and police brutality,” said Gary Shiffman, Brookline High's curriculum coordinator. “I think we’re all very aware that two years ago America blew up again over race, and I think that’s affected the way we teach.”

The curriculum will span all departments and programs. For the first time this year, sophomores are offered a class called “Race and Identity,” led by social studies teachers Malcolm Cawthorne and Kate Leslie. Leslie said she considers it her duty to open up the dialogue about race and offer her students a chance to share their experiences.

“I completely believe that white people have to be involved in talking to other white people about race and racism. It’s really a white person’s problem,” said Leslie. “This is a white person’s problem in that we’re the ones perpetuating it. And therefore I think white people need to be talking and working with other white people to dismantle the system that’s in America.”

Erdmann is encouraged that schools are now tackling this issue, and she cautioned that this work should not be a mission solely for schools with minority students.

“It could be an all-white school — even more reason to talk about it," she said. "You know, 'We’re not integrated; how did that come to be?' Let’s have that discussion, look around. 'There aren’t any black kids; how did that come to be?' 'How are schools funded, and where do people live, and what about redlining?' I would start with what’s right in front of you.”

Erdmann believes the only way to move past racism is to teach kids the full story about race and racial history, empower them to fight against it, and then, she said, move out of the way.

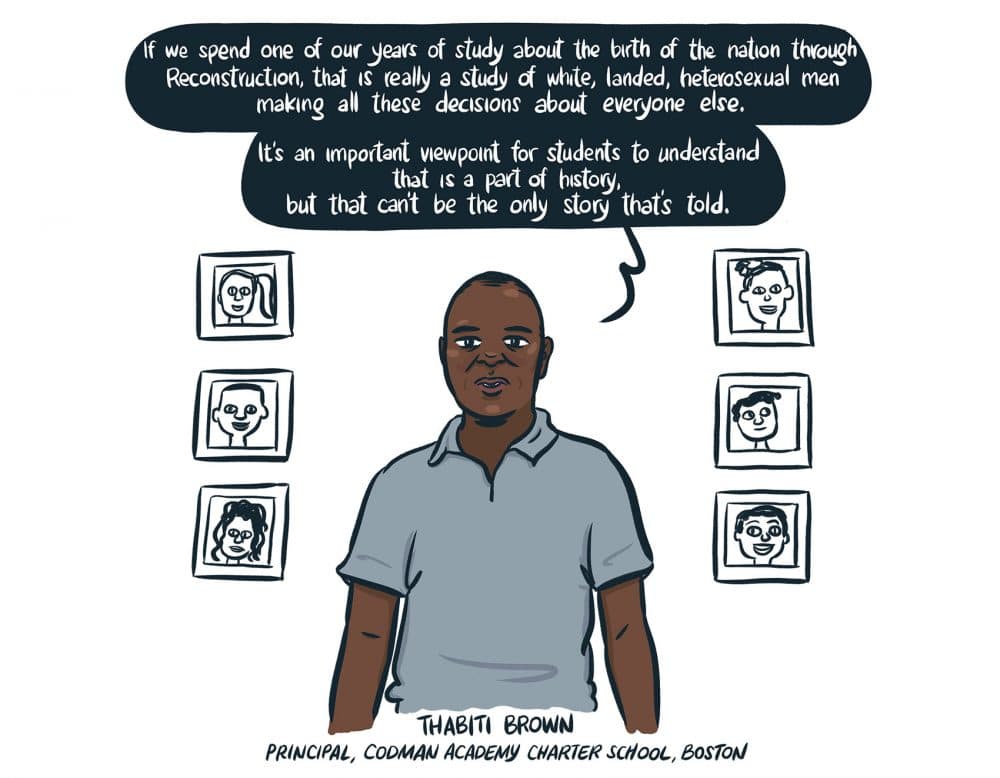

In part 1 of this series, Thabiti Brown and others talk about teaching racial history.

This segment aired on September 20, 2016.