Advertisement

5 Poetry Books With A Boston Connection You Should Read

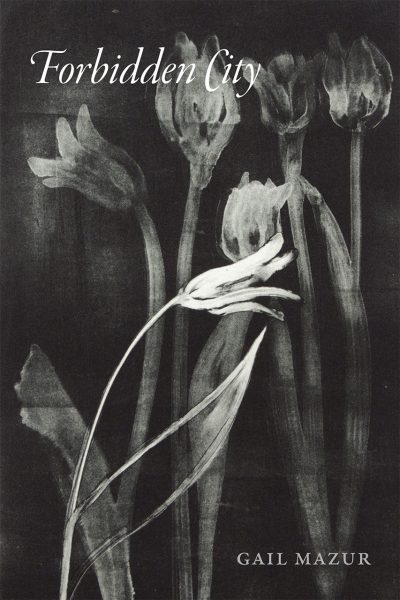

The ARTery has asked me to choose my five favorite poetry books published this past year. Since that's an impossible limitation, I've decided to restrict my choices only to books by people with direct ties to the Boston area (i.e., Cambridge). That means I won’t be mentioning Rita Dove’s awe-inspiring “Collected Poems” (a National Book Award finalist), Ocean Vuong’s challenging and edgy “Night Sky with Exit Wounds,” or Alan Shapiro’s engaging, unsparing new “Life Pig.”

That disclaimer out of the way, these are my nominees for the five most deeply satisfying poetry volumes written — or edited — by some of our greatest Greater Bostonians.

1. “Forbidden City,” by Gail Mazur (University of Chicago Press)

In the title poem of Gail Mazur’s seventh book of poems, her most heartbreaking and her most expansive, she raises the question of time:

Time is the treasure, you tell me,

and the past is its hiding place.

I instruct our fictional children,

The past is the treasure, time

is its hiding place.

Mazur is one of our treasures — not only as a poet but as a teacher (at Emerson and, this spring, at BU), Ploughshares guest editor, and founder of the legendary Blacksmith House Poetry Series. In “Forbidden City,” poems about her writing life, her family and the loss of her husband, the artist Michael Mazur, are placed in a broader context by a section of extraordinary poems about the nature of art. I’d like to quote one of them in full, partly because I love it, partly because it’s short, partly because it’s a poem of deep but unpretentious wisdom, and partly because in some way it encapsulates what all the poets — all the artists — I admire most do best: pay attention to the world around them.

"Philip Guston"

Everything, he said,

has a form,

even doubt has a form,

he said, walking away

from class,

the painting students

all puzzlement

at their easels, left there,

with a week

to wonder.

Class over, but he, still

teaching.

On Comm Ave

a blue parked truck

with bright red lettering --

Look at that,

he said, Look

at that.

2. "At the Foundling Hospital," by Robert Pinsky (FSG)

Our three-term poet laureate and founder of the Favorite Poem Project has a new book, which is always an occasion to celebrate.

“At the Foundling Hospital” is one of his most personal, funniest and saddest (at his recent Blacksmith House reading, he said that for him “foundlings represent the human condition”). His poem “Grief” is classic Pinsky. The “Mike” he refers to is the aforementioned Michael Mazur, the poet’s dear friend and the artist who did the unforgettable illustrations for his landmark translation of Dante’s “Inferno.” This definition of grief rings completely and universally true.

"Grief"

I don’t think anybody ever is

Really divorced, said Lenny. Also,

I don’t think anybody ever is

Really married, he said. Because

English was really his second language

And because of Yiddish and its displaced

Place in the world, he never really

Believed in his own prose. He wrote

Sentences the way a great boxer moves.

Near the end he told me “I’m in Hell” --

Something Lenny might have said about

Hunting for a parking space in Berkeley.

Mike too was himself. His last month,

Too weak to paint or make prints,

He sat and made drawings of flowers:

Ink attentive to rhythms of beach rose,

Wisteria, lily — forms like acrobats

Or Cossack dancers. Mike had a vision

Of his body dead on his studio floor

Seen from high above — he didn’t feel sad

Or afraid at seeing it, he said, just

Sorry for the person who would find it.

You can’t say nobody ever really dies:

Of course they do: Lenny died. Mike died.

But the odd thing is, the person still makes

A shape distinct and present in the mind

As an object in the hand. The presence

In the absence: it isn’t comfort — it’s grief.

Advertisement

3. "Standoff," by David Rivard (Graywolf)

I could have chosen David Rivard’s new collection not because I’m so moved by it (I am!) but just because there’s a terrific Philip Guston painting reproduced on the cover. It’s a great cover, but it’s also Rivard’s most intimate and affectionate book. What are currently my two favorite poems of his are both in “Standoff.” Here’s a memorable passage from the piercing “Said,” a poem that about visiting his dying father (the ellipses are Rivard’s — I’m not leaving anything out):

Later he said . . . he’d said

earlier . . . then I said . . . he

said . . . I said . . . I said . . .

I said. . . . Say now that

this might be all that’s left

for consolation.

And there’s the wonderful poem I regard as the best poem written by a father to his daughter after Yeats’ “A Prayer for My Daughter”:

"Birth Chart"

to Simone

Wandering off under those astrological signs

charted just for you, my quiet trekker — all

those houses & planets perfectly straight-faced

but still baffling at birth — don't think badly

of me when I'm dead & you've gone deep

into the distance of love tangles, moneyed

interests, & old fashioned commutes — into life

in other words — I did what I could for you, knowing

it might not be enough — I see now that I can't

save you from suffering, & trying to hurts

if I'm not kind. Tho I still want your life to be

untroubled, & am afraid for you, a fear made

out of my own fear of a future I can't control --

the world so often a human heart that eats itself --

places like New Orleans the Swat Valley Fukushima --

the names of those remote destinations for film crews

and symposium panels are places people die

native to those regions & out to kill or defend

life from itself — there is so much misery there

that refuses to call itself misery & that sees itself

instead as the unimpeachable power of a righteous day.

And there are criminals & dunces elsewhere --

Hideous partyline whips, Saxon in outlook

and proud of it — there are the bodysnatched

and the inane candy-stripers & the greedy

and the martini narcissists high on the rising year --

but let's take the long view: these are not

your true companions, & out of my reach your

life will make itself in struggle & love perhaps

dependent on the strength that will come

if I only let go when you step out the door

now as hazel-eyed as always & maybe more so

this morning in slate-grey Gore-Tex.

4. “Admit One: An American Scrapbook,” by Martha Collins (University of Pittsburgh Press)

“Admit One” (the cover of the book is an image of a torn ticket stub) is the third of Martha Collins’ devastating and outraging volumes dealing with issues of race in America (the first of these, “Blue Front,” is the award-winning book-length poem about a lynching Collins’ father witnessed as a child in turn-of-the-century Cairo, Illinois).

“Admit One” is also a book-length poem, and is so organically put together it’s hard to excerpt. It’s a history of “scientific racism,” from the time of the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 through the eugenics movement of the '20s, with its horrific influence on Nazi Germany.

One thread is the poignant story of Ota Benga, the Mbuti pygmy who was exhibited at the St. Louis Fair and later at the Bronx Zoo (several years after his release he committed suicide at the age of 32).

Another is the story of Carrie Buck, a victim of sterilization. Gripping and mind-bending in its inventiveness, this is not a book for the faint of heart, but it now seems more important than ever to read it.

"The Zoo"

zoo- logical garden plant

an antelope elephant tree

zoo- logical park as in

enclosure meant for game

for us we parked

the car could leave

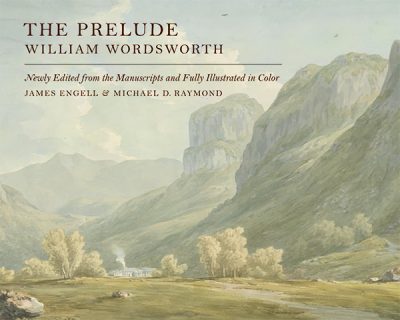

5. “The Prelude,” by William Wordsworth, edited by James Engell and Michael D. Raymond (David R. Godine)

Wordsworth’s long poem addressed to Coleridge, posthumously titled “The Prelude or, Growth of a Poet’s Mind,” was his radical reimagining of what an epic poem could be. He completed a draft of this masterpiece in 1805, at the age of 35 and at the height of his powers, then revised and revised it for more than three decades. It was finally published shortly after his death in 1850. Most literary critics and scholars feel he revised most of the life out of his original version.

Now the distinguished Harvard professor of English and comparative literature James Engell has re-edited the 1805 version from its original manuscripts, written a lucid introduction and useful, illuminating notes, and with his co-editor, Wordsworth scholar (and financial adviser!) Michael D. Raymond, assembled a book that is a marvel — beautifully illustrated with 130 full-color paintings, drawings, maps and other visual aids contemporaneous with the writing of the poem.

Even aside from the great poem itself, it’s a book that’s hard to put down. But once you start reading the poem, in which the poet takes us along with him through his soul-searching “spots of time” — haunting and mesmerizing recollections of his childhood in the Lake District, his walking trip across the Alps and his experience of the French Revolution — you can’t put that down either.