Advertisement

Solving Our Math Problem

How Data Is Driving A Math Turnaround At Boston's English High

After a school has struggled for a while, sudden progress can sometimes be hard to believe.

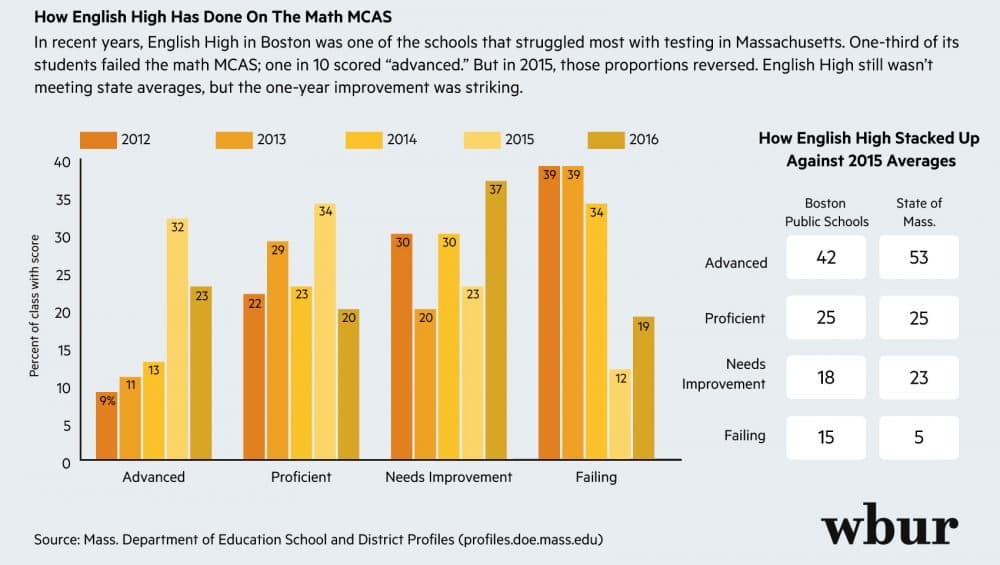

The English High School in Boston shocked the state with a dramatic jump in its math scores on the MCAS exam in 2015. The percentage of students scoring "advanced" more than doubled, while the percentage of those failing shrank by two-thirds.

State officials withheld those scores for weeks for what the education commissioner called "anomalies" before certifying them as legitimate.

Many of the sophomores who impressed everyone with their math scores two years ago are now seniors, with their eyes on graduation.

Carmen Bernabel still remembers the extra work they all did before the 2015 test.

The pride, she says, is mixed with pain — that at first, state officials didn’t trust the scores: "I remember that they thought that we cheated. The entire sophomore class was mad. Just because we come to English High — that’s what we thought about it. 'How can Hispanics and black kids have such an improvement in, like, math scores?' But it's possible.”

Other teachers and students agree: The progress is real. And two years later, they credit a system of individualized education, building skills and rebuilding confidence, student-by-student.

English High — which self-identifies as "America's oldest public high school" — is coming off some of the most difficult years in its history. In 2010, it and 11 other Boston schools were named "Level 4" schools, among the state's worst performers.

It's weathered a wave of out-of-school suspensions — in the 2013 school year, one in 7 students was kept out of class. Enrollment has dwindled by 50 percent in the past 10 years. And the same spring that Carmen Bernabel's class took the MCAS, the school was shaken when a dean was charged with the attempted murder of a student.

And the school is among the city's more diverse: Just 2 percent of its students are white. More than two-thirds come from low-income households, and according to school leaders, more than half of the school's students are English-language learners. Nationwide, schools like English High persistently lag behind their better-resourced peers.

Advertisement

That "achievement gap" has obsessed education experts for decades. But tests and studies show that it's been very hard to close.

Ligia Noriega-Murphy, the school's headmaster, is an immigrant like many of her students; she grew up in Guatemala. She talks fast, and identifies so many ideas that it’s hard to arrive at a one-sentence summary of her strategy for turning things around at English High.

Eventually, she arrives at a metaphor for how she wants to treat her students, straight out of Silicon Valley: "We see them as clients. They're going to be successful if we really pay attention to their individual needs."

Think Amazon or Netflix: tracking, customization and relentless catering to the customer.

But English High’s students don’t need movie recommendations, or monthly shipments of detergent. They need the skills that will serve them in college and beyond — and the confidence to know they can learn them.

Before summer vacation ends, English High teachers review the academic records of each new freshman — going back as far as the first grade.

And in math especially, teachers begin the year by discovering what their student body can do, from addition to advanced algebra.

There are the math stars you find in any group of students: teenagers who love numbers. But there are also some formidable gaps.

"Sometimes we notice they lack the basic skills," Noriega-Murphy says. "They cannot add more than two digits. Or they don’t know how to read, and they’re 15 years old.”

So much of math instruction is cumulative; this week’s lesson builds on what you learned the week before, which builds on what you learned in first grade. So English High teachers have to build up college-level skills even as they reinforce the mathematical foundations down below.

Noriega-Murphy and her team have a mantra: Meet the students where they are.

"I think the frustration that sometimes comes from students in the past is, 'If I don't learn this, I'm done. Forget about me; they're going to move forward.' We can't do that," she says.

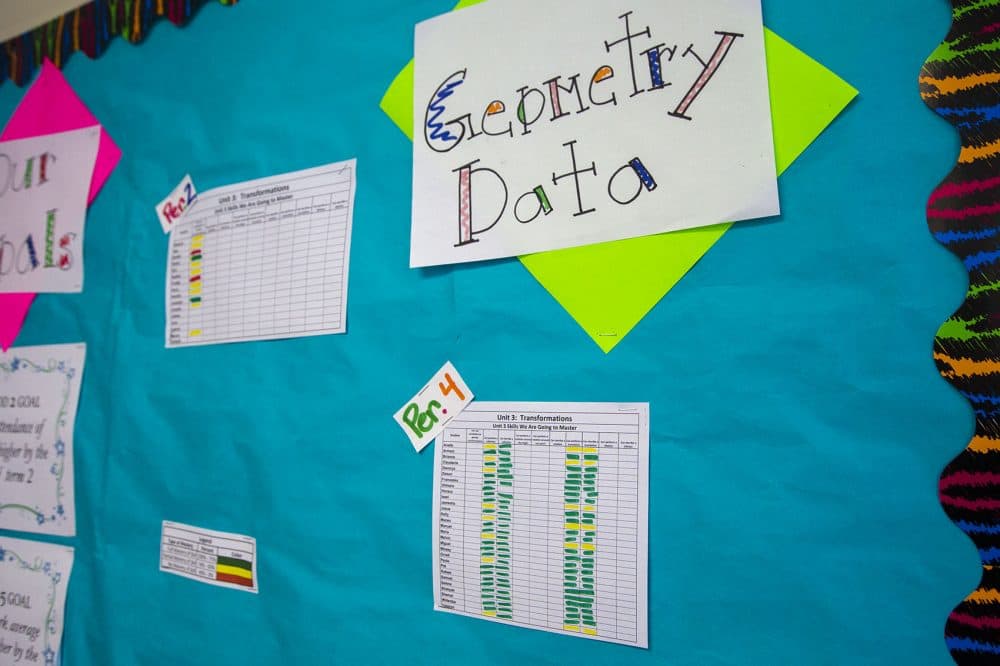

All the math classes are grouped together on the school's fifth floor. At the back of every classroom, there are big paper displays marked with red, yellow and green dots.

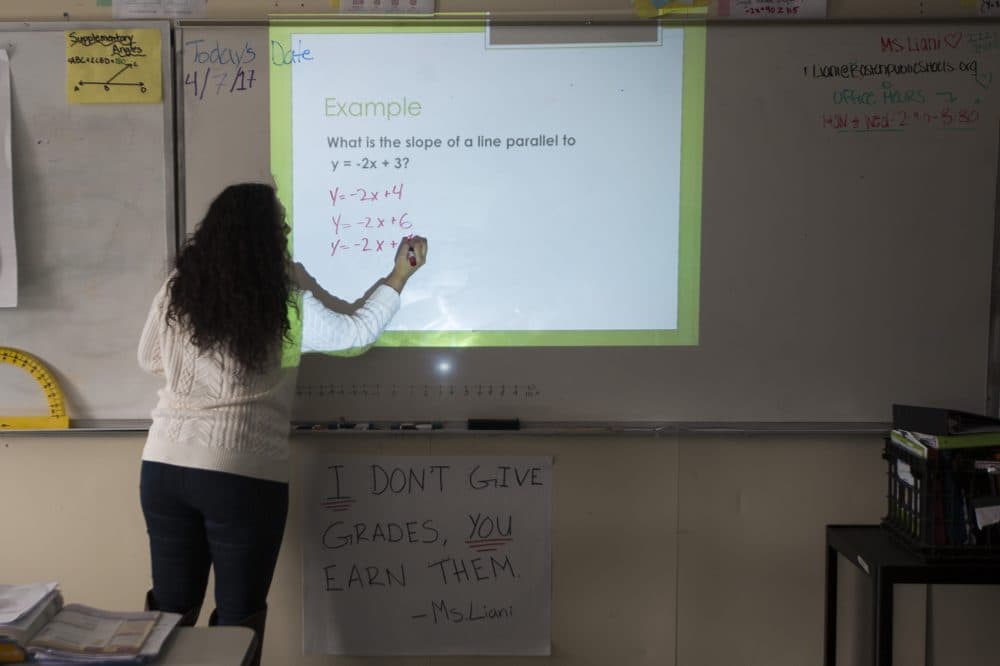

The dots are "data trackers." And teacher Roma Liani says they paint an evolving picture of how her students are handling the material. This week, that means manipulating shapes on a plane.

At 24, Liani is already the teacher-leader of English High's entire math faculty. She says her students check the board, chasing the green dots that mean they've mastered the latest unit. “They take a look, and they get kind of bummed. ‘Yellow? Why is this yellow?’ ” she says. “I’m like, ‘Well, let’s go back and look at the work: why is it yellow?' "

That information doesn't just live on the wall — teachers share it among themselves in online databases. In weekly meetings, they parse the numbers together and decide on tailor-made lesson plans for every student.

It's a struggle, Liani says: "It's not always, 'We're not all going to learn the same exact thing today.' It's, 'What can I get you to learn today?' It's a lot of work: It's sometimes making 28 different packets for 28 different kids."

That flexible philosophy goes beyond worksheets. A student who has historically done better with a male teacher will find a man at the front of the class whenever possible.

Some young people need a friendly face; others benefit from running around in PE before they sit down to do algebra. School leaders do the best they can to meet their needs; Noriega-Murphy calls it "the magic of scheduling."

Of course, sometimes students' problems with math are more stubborn — the dots stay red.

For example, senior Gleysis Gonzalez likes math when she gets it. But she struggled with stress and confusion before being scheduled into math mentoring. That meant that for an hour at the end of every school day, she sat alongside a classmate chosen for their empathy as well as their mastery of math.

Gonzalez says that made all the difference. Where her teachers had to move on, a peer mentor could linger on the most difficult topics.

"For a whole three days," she says, "we would stay in that topic — over and over and over again, as many times as you need."

That mathematical pit stop means pulling struggling students out of an elective, or gym, for as long as it takes to catch them up.

But Noriega-Murphy says it's worth it. "That's where they get the extra support. We know that when they mastered that, they can go back to the regular class — they're still in the regular class. They feel very confident; they say, 'Oh, I got it.' "

Tackling gaps in skills with patience, persistence and attention to detail — that's how English High is trying to make progress.

But Noriega-Murphy admits her approach is not a cure-all. Sometimes all the data-gathering does is warn teachers of trouble ahead.

Last year's sophomores struggled particularly with literacy — and that held them back in other subjects. “There were concerns. I remember Miss Liani running in here and saying, 'We have a problem!’ " she remembers, laughing. "'Well, what is the problem?' The gaps were really acute. So that was a challenge."

When last year's math scores came back, they were below the high water mark set in 2015. But they were a lot higher than they had been before the data revolution came to English High.

Noriega-Murphy says her team is learning from the setback. They're reaching out to middle schools to make sure incoming freshmen are better prepared. And she and all of English High will be watching closely in the fall, when the scores come back for this year’s sophomores.

Reading the data at the back of her math classrooms, she says, the signs are good.

This article was originally published on April 10, 2017.

This segment aired on April 12, 2017.