Advertisement

Review

Faith And Reason Collide In Central Square Theater's 'Paradise'

It’s a clash of civilizations — or at least polemics — at the Central Square Theater with the premiere of Laura Maria Censabella's "Paradise." This is an impeccably structured play about love and passion, but somehow I came away feeling that I’d seen a cooking show.

Censabella skillfully gathers all the ingredients for a boiling drama that simmers away for two hours: Faith faces off against reason, and American ideas of freedom and individuality knock up against more venerable traditions of self-sacrifice for a community and its uniformity of conduct and belief. Once the characters have aired their arguments and struck their compromises, however, what we’re left with feels a little prepackaged and lukewarm.

“Paradise,” a production of Underground Railway Theater with the support of Catalyst Collaborative@MIT through May 7, brings together two inquisitive characters who each have personal as well as professional reasons for wanting to explore the neurological basis of romantic love.

Yasmeen al-Hamadi (Caitlin Nasema Cassidy), a brilliant teenager and pious Muslim, faces two starkly forking paths: She could seize a rare opportunity for a top-flight education and a career in science, or she could go through with an arranged marriage and restrict her own life but help support her family. Dr. Guy Royston (Barlow Adamson), meanwhile, is a former Ivy League professor who’s now teaching at Yasmeen’s poorly performing public school in the Bronx, in retreat from the wreckage he made of his family and career after a mad love affair and the poor choices it spawned.

It’s easy to see, if not articulate, the dream they’re both chasing, which is a sort of modern alchemy. If love could be understood, then perhaps it could be guaranteed. We could follow a system for matchmaking (perhaps not so different from the arranged marriages Yasmeen’s family knew in Yemen) or, alternatively, we could get inoculated against Cupid’s arrows until we’re ready to approach the whole dating-and-mating thing from a more rational, and less destructive, place of mental and emotional preparation. Understanding is the key to liberation — or so we’d like to think in our enlightened times. But human nature has a way of slipping every leash we try to put around its neck.

People are not rational, after all, and in many ways they are fundamentally selfish. Censabella never loses sight of this, and she builds her play organically around the implicit conflict between reason (which ideally is unsentimental) and tradition (which often carries a tinge of superstition and irrationality). Dr. Royston genuinely comes to care for Yasmeen, but his mentorship is closely tied to his fervent hope that her insights could help make him the principal investigator on a significant paper. That paper could, in turn, rehabilitate his reputation and, as he puts it, get him off the “blacklist” that prevents his return to the rarefied circles of scientific academia. In short, he’s the usual ambitious male.

Yasmeen, by contrast, feels so obligated to her aunt and uncle — the relatives who took her and her sister in after their parents died — that she systematically rejects Royston’s logically laid out arguments about why, and how, she needs to lay the groundwork for her own future. She’s concerned for her family, of course, but she’s also engaged in relentless and sometimes insidious forms of self-sabotage, which casts her in the role of the typical “nurturing” (or self-abnegating) female. These are standard tropes, but they remain powerful, and Censabella comments meaningfully on the cross-cultural persistence of such gender-related baggage.

There’s a great deal of nuance to all of this, and it comes across beautifully, thanks to Cassidy’s and Adamson’s commitment to their characters. Cassidy’s Yasmeen is a study in challenges to assumptions. She wears a hijab, and she worries about how her family and culture could close in and suffocate her — one word of malicious gossip from a male acquaintance could annihilate her good name and bring her family to shame. Even being alone with an unrelated man, as she is throughout the play with Dr. Royston, could constitute an unpardonable breach of decorum. But at the same time, she’s feisty and smart, and her New York accent marks her out as a contemporary city woman. Struggle though she might with old-school traditions, there’s no mistaking Yasmeen for anything but a 21st-century American.

Adamson (a longtime Boston favorite who recently impressed as a British veteran of Ireland’s “troubles” in “The Honey Trap” at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre) takes on an accent, too, as a man from Virginia. In Yasmeen he thinks he sees a kindred spirit — a clever and curious person who must escape an oppressive religious tradition in order to flourish. Again and again he discounts the value of her faith — yet despite his thin skin and sometimes reflexive prejudice, he’s also a scientist, and he acts accordingly. When Yasmeen makes it clear that she doesn’t appreciate his dismissive comments about her religion and culture, he takes it to heart and incorporates that lesson into his world view; he even comes to appreciate the sacred writings of the Quran and the beauty of Muslim calls to prayer.

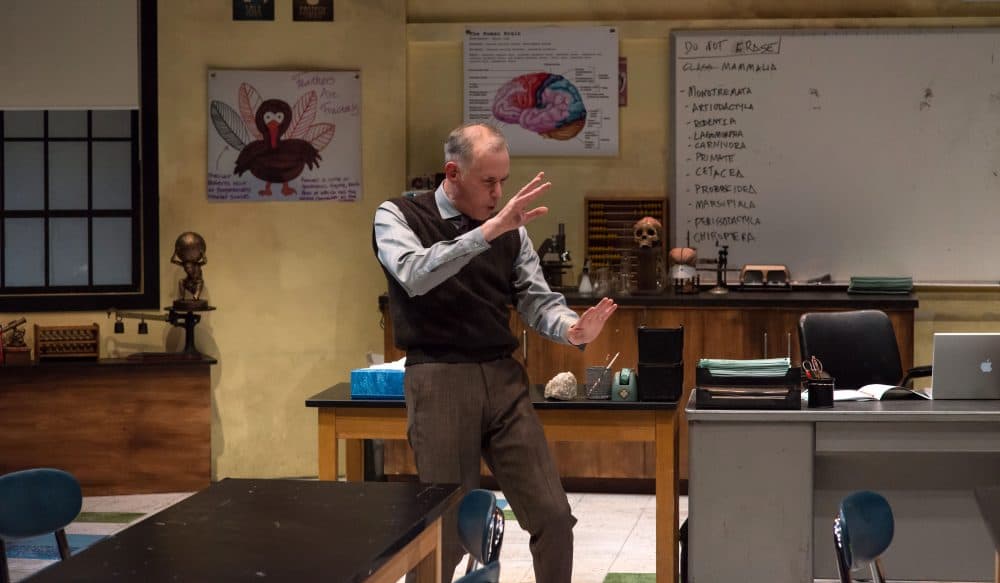

Under Shana Gozansky’s direction, the material builds tension that, time after time, releases into a good long laugh. The beats are perfectly timed. Karen Perlow’s lighting and Nathan Leigh’s sound design work wonderfully, and costume designer Gail Astrid Buckley knows just what kind of sweater to wrap Dr. Royston in and when it needs to be on his shoulders as opposed to hanging in readiness on a nearby hook. And the set, by Jenna McFarland Lord, so faithfully re-creates a high school science classroom that for a moment I felt compelled to look for my old chair.

What works less smoothly is the shift in tone when Yasmeen complains that "boaters" — recently arrived Muslim immigrants — go out of their way to make life miserable for more established Muslim-Americans, or when she tells Dr. Royston with a note of panic that, above all else, he cannot ever let her family know he’s serving as her mentor. Life and the things that make it precious — including family and faith — will never be perfectly self-consistent, but there’s an awfully big gap between Yasmeen’s love for her cultural roots and her frank terror of the consequences she’ll suffer if she crosses any of the lines that faith and family draw around her.

Not that such a gap seems improbable; it doesn’t at all, and that’s why the play should address it more fully. A brighter, harsher and more dramatic light glints through the chinks of this play’s walls — which are sometimes too neatly drawn — and it’s hard not to want to see more than these few tantalizingly discordant hints of that outside glare.

At the same time, although Yasmeen’s efforts to increase Dr. Royston’s cultural sensitivity yield some remarkable growth on his part, the play itself never quite gets away from his initial, dismissive attitude toward Yasmeen’s Yemeni roots. “‘American stuff’ is freedom,” he says early on, and that idea seems to lurk beneath the whole play, not as a debatable proposition but as an axiom that cannot be challenged or even revised.

The production fits handily within the Central Square Theater’s recurring theme of women in science, and Censabella’s script makes rigorous arguments from both characters’ points of view. But the ultimate — and elegant — conclusions in “Paradise” don’t feel entirely earned.